The Pura Belpré Awards turns 20 this year! The milestone will be marked on Sunday, June 26, from 1:00-3:00 p.m. during the 2016 ALA Annual Conference in Orlando, FL. According to the award’s site, the celebration will feature speeches by the 2016 Pura Belpré award-winning authors and illustrators, book signings, light snacks, and entertainment. The event will also feature a silent auction of original artwork by Belpré award-winning illustrators, sales of the new commemorative book The Pura Belpré Award: Twenty Years of Outstanding Latino Children’s Literature, and a presentation by keynote speaker Carmen Agra Deedy.

Leading up to the event, we will be highlighting the winners of the narrative and illustration awards. Today’s spotlight is on Eric Velasquez, the winner of the 2011 Pura Belpré Illustrator Award for Grandma’s Gift.

Review by Lila Quintero Weaver

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Every year, Eric spends his winter break with his grandmother in El Barrio while his parents are at work. There’s much to do to prepare for Christmas, including buying all the ingredients for Grandma’s famous pasteles, a special Puerto Rican holiday dish.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Every year, Eric spends his winter break with his grandmother in El Barrio while his parents are at work. There’s much to do to prepare for Christmas, including buying all the ingredients for Grandma’s famous pasteles, a special Puerto Rican holiday dish.

But Eric also has an assignment for school that requires a trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see a new painting. Grandma and Eric are nervous about leaving El Barrio but are amazed by the museum and what they see in the painting—a familiar face in a work of art by the great painter Diego Velázquez. That day Eric’s world opens wider, and Grandma knows the perfect gift to start him on his new journey.

In this prequel to Grandma’s Records, Eric Velasquez brings readers back to a special day spent with his grandmother that would change his life forever.

MY TWO CENTS: Eric Velasquez is the award-winning illustrator of more than 25 children’s books, including three that he wrote. In Grandma’s Gift and Grandma’s Records, reviewed here, Eric brings to life childhood moments that illuminate the warm and meaningful relationship he enjoyed with his grandmother, a native of Puerto Rico and resident of El Barrio, a predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood in East Harlem.

In a category where such books are woefully rare, both of Velasquez’s Grandma stories represent positive images of Afro-Latinx children and their families.

Although the story in Grandma’s Gift takes place inside a few square miles of contemporary New York City, it also casts a spotlight on a long-ago historical figure. Juan de Pareja was an enslaved man of African descent who worked in the studio of 17th-century Spanish master Diego Velázquez and who became a painter in his own right. When Eric was a boy, Velázquez’s luminous portrait of de Pareja was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a price exceeding $5 million.

Grandma’s Gift contains two additional distinguishing aspects: elements of Puerto Rican culture preserved and passed down by the boy’s grandmother, and contrasting views between two physically proximate but culturally distant worlds, represented by El Barrio and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Used by permission from Bloomsbury Publishing, Inc.

At the story’s beginning, Eric is leaving school for Christmas break, in the company of his grandmother. His school assignment, to be completed during the holidays, is a visit to the Velázquez exhibit. But first, grandmother and grandson go shopping at La Marqueta, once a central feature of El Barrio, composed of bustling shops tucked under a railroad trestle. At La Marqueta, it’s evident that Eric’s grandmother is a respected and beloved member of the community. Not only do butchers and greengrocers call her by title and name—Doña Carmen—they are also familiar with the high standards she expects from every cut of meat and vegetable she purchases. When the shopping is done, Eric and his grandmother return to her apartment, where she launches an elaborate preparation of traditional Puerto Rican holiday dishes. Here, she is clearly in her element, deftly handling each step of the cooking, filling, and rolling of the pasteles, much to the admiration of young Eric.

Used by permission from Bloomsbury Publishing, Inc.

Nearly all of Doña Carmen’s dialogue is parenthetically translated into English, immediately behind her Spanish words. While this solution is not particularly elegant, it reflects the challenge that authors and publishers face in including authentic representations of a Spanish-speaking environment within an English text. The story translates greetings in Spanish by shopkeepers, words of wisdom spoken by the grandmother, and details relevant to the story, such as the names of the root vegetables used in making pasteles: calabaz, yautía, plátanos verdes, guineos verdes, papas.

El Barrio is a place that Eric’s grandmother comfortably navigates day after day. Here, her native tongue predominates, and everyone is a shade of brown. But when she and Eric head for the museum, a short bus ride away, they leave behind that familiar environment and land before the facade of the Metropolitan, cloaked in cultural status and imposing architecture. As Eric notes, there’s no one “from Puerto Rico on the streets and no one was speaking in Spanish.” At this point, Eric becomes her guide in this English-speaking world, translating the signs and captions that they encounter, stepping into a role that second- or third-generation immigrant children often play in their elders’ lives.

Juan de Pareja, by Diego Velázquez

The highlight of the story arrives when Eric comes face to face with the portrait of Juan de Pareja, hanging in its gilded frame in one of the august exhibition halls of the museum. As a young person of color in the 1970s, he has never seen a member of his own people elevated to such a status: “He seemed so real—much like someone we might see walking around El Barrio. I couldn’t believe that this was a painting in a museum.” Eric is amazed and proud to learn that Juan de Pareja eventually achieved freedom and became a painter in his own right. For Eric, this discovery is a revelation that sparks artistic fire. On Christmas Eve, after everyone enjoys a traditional holiday dinner, Eric sits under the Christmas tree and opens his grandmother’s gift. It’s a sketchbook and a set of colored pencils. He immediately begins to draw a self-portrait. Through this gift, Eric’s grandmother expresses a clear vote of confidence in her grandson’s dreams, underscoring that he, too—a child of El Barrio, an Afro Latino—can follow in the footsteps of Juan de Pareja.

Flight into Egypt, by Juan de Pareja

This touching, autobiographical story is richly illustrated in Velasquez’s photorealistic style, which authentically depicts settings and brings dimension to each character. Eric imbues his subjects with individually distinct physical characteristics, lending to each an air of nobility. He lovingly paints his grandmother as a lady of dignified bearing and warmth, usually dressed in subdued colors. But he often lavishes this humanizing treatment even on background characters, such as fellow passengers on the train and a nameless guard at the museum. In most of the illustrations, Eric employs a wide and vivid range of hues, but like Diego Velázquez, he sometimes falls back on a deliberately limited palette. When the boy and his grandmother stand before the portrait of Juan de Pareja, the rich browns of the ancient oil painting harmoniously come together with the rich browns of the grandmother’s clothing, as well as the skin tones of all three figures. He puts this deft touch with a monochromatic palette to great effect in the story’s electric moment of revelation, as the child Eric looks on the portrait of Juan de Pareja and grasps a new possibility for his future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR: Eric Velasquez is an Afro-Puerto Rican illustrator born in Spanish Harlem. He attended the High School of Art and Design, the School of Visual Arts, and the famous Art Students League in New York City. As a children’s book illustrator, Velasquez has collaborated with many writers, receiving a nomination for the 1999 NAACP Image Award in Children’s Literature and the 1999 Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award for New Talent for The Piano Man. For more information, and to view a gallery of his beautiful book covers, visit his official website.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR: Eric Velasquez is an Afro-Puerto Rican illustrator born in Spanish Harlem. He attended the High School of Art and Design, the School of Visual Arts, and the famous Art Students League in New York City. As a children’s book illustrator, Velasquez has collaborated with many writers, receiving a nomination for the 1999 NAACP Image Award in Children’s Literature and the 1999 Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award for New Talent for The Piano Man. For more information, and to view a gallery of his beautiful book covers, visit his official website.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Learn more about El Barrio from the definitive museum that bears the same name.

After decades of decline, La Marqueta is attempting a comeback. (This article is in Spanish.)

Here, a resident of El Barrio relates her memories of La Marqueta during its heyday.

See the official page for the Juan de Pareja portrait on The Met’s website.

Lila Quintero Weaver is the author-illustrator of Darkroom: A Memoir in Black & White. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Darkroom recounts her family’s immigrant experience in small-town Alabama during the tumultuous 1960s. It is her first major publication. Lila is a graduate of the University of Alabama. She and her husband, Paul, are the parents of three grown children. She can also be found on her own website, Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

Lila Quintero Weaver is the author-illustrator of Darkroom: A Memoir in Black & White. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Darkroom recounts her family’s immigrant experience in small-town Alabama during the tumultuous 1960s. It is her first major publication. Lila is a graduate of the University of Alabama. She and her husband, Paul, are the parents of three grown children. She can also be found on her own website, Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Judith Ortiz Cofer was born in Hormigueros, Puerto Rico and grew up in Paterson, New Jersey, two locations that have inspired her work. She has written for all ages – children’s and young adult books including ¡A bailar! / Let’s Dance! (2011), The Poet Upstairs (2012), Animal Jamboree (2012), Call Me Maria (2006), and If I Could Fly (2011), and books of poetry and prose for adults, including The Meaning of Consuelo (2003) and the Pulitzer Prize-nominated The Latin Deli (1993). Her work has won various prizes and honors, such as the Pushcart Prize and the O. Henry Prize and has appeared in several literary anthologies. Moreover, she has received fellowships at Oxford University and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. Currently, she lives in Georgia and is the Regents’ and Franklin Professor of English and Creative Writing, Emerita.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Judith Ortiz Cofer was born in Hormigueros, Puerto Rico and grew up in Paterson, New Jersey, two locations that have inspired her work. She has written for all ages – children’s and young adult books including ¡A bailar! / Let’s Dance! (2011), The Poet Upstairs (2012), Animal Jamboree (2012), Call Me Maria (2006), and If I Could Fly (2011), and books of poetry and prose for adults, including The Meaning of Consuelo (2003) and the Pulitzer Prize-nominated The Latin Deli (1993). Her work has won various prizes and honors, such as the Pushcart Prize and the O. Henry Prize and has appeared in several literary anthologies. Moreover, she has received fellowships at Oxford University and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. Currently, she lives in Georgia and is the Regents’ and Franklin Professor of English and Creative Writing, Emerita. Marianne Snow Campbell

Marianne Snow Campbell

In my book,

In my book,

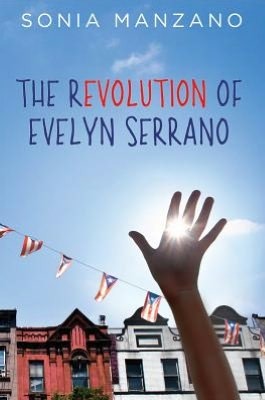

By Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez

By Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez