By Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez

As a child what I desired most was to be rescued from the violence I experienced at home. I was undocumented and domestic violence was far too common. While I now know that these are real experiences for many Latino homes, these were secrets that I walked around with for fear that my family would be separated if I said anything. Retrospectively, what I probably needed, aside from the violence to stop, was to understand why the violence was happening in the first place. There was nothing or no one around to explain my feelings of anxiety, fear, and/or self-hate around the violence I witnessed and then internalized. At the time, shows like “Boy Meets World,” “Saved by the Bell,” and “Full House” only reaffirmed for me that my family was different, did not belong, or that there was something wrong us. I was reading a lot, too, but I only got more and more frustrated that the books I read did not speak to my reality. I was obsessed with Beverly Cleary’s Ramona because she was everything I wanted to be—free, adventurous, and happy. And while characters like Ramona fueled my imagination they explained nothing about the violence I endured.

My investment in Latina/o children’s and young adult literature stems from my desire to explain why violence is more prevalent in certain communities than it is in others. But it is also driven by what I have seen is the genre’s potential to provide paths toward healing for Latina/o children and young adults. Recent conversations about the need for diversity in children’s literature have discussed at length the impact that being or not being represented in books can have on a child’s self-esteem and where they see themselves positioned in society. These conversations have made visible the discrimination within publishing industries and the ways that children of color stand to lose the most. Diversity is important to my project simply because stories about children of color can save their lives.

I was first introduced to Luis J. Rodriguez’s América is Her Name as a graduate student and it was the first children’s book I read with a Latina protagonist. I was a taken aback that a kid’s book actually talked about immigration and included scenes of violence. Mainstream children’s literature is no stranger to violence, gruesomeness, monsters, and the like; however, it is out of the ordinary to see a story about immigration, gang violence, and abuse at home that does not depend on stereotypes or is read as ethnography. América Soliz, the protagonist, is a recent immigrant from Oaxaca, Mexico to Pilsen, Illinois— one of Chicago’s predominantly Mexican communities— who struggles to find a voice in a place that seeks to silence her. Throughout the text, the reader is privy to the discrimination she faces in the classroom, the violence in her community, and the patriarchal oppression in her home. What I found most powerful about the book was that América is given a tool to challenge the oppressions around her. Poetry becomes her outlet, and it allows her to process the violence she witnesses and experiences. In this way, the violence does not overwhelm her, but instead, she is able to find strength despite it. Rodriguez’s book opened a new world of children’s books for me, and it allowed me to see this genre as having the potential to create social change.

I was first introduced to Luis J. Rodriguez’s América is Her Name as a graduate student and it was the first children’s book I read with a Latina protagonist. I was a taken aback that a kid’s book actually talked about immigration and included scenes of violence. Mainstream children’s literature is no stranger to violence, gruesomeness, monsters, and the like; however, it is out of the ordinary to see a story about immigration, gang violence, and abuse at home that does not depend on stereotypes or is read as ethnography. América Soliz, the protagonist, is a recent immigrant from Oaxaca, Mexico to Pilsen, Illinois— one of Chicago’s predominantly Mexican communities— who struggles to find a voice in a place that seeks to silence her. Throughout the text, the reader is privy to the discrimination she faces in the classroom, the violence in her community, and the patriarchal oppression in her home. What I found most powerful about the book was that América is given a tool to challenge the oppressions around her. Poetry becomes her outlet, and it allows her to process the violence she witnesses and experiences. In this way, the violence does not overwhelm her, but instead, she is able to find strength despite it. Rodriguez’s book opened a new world of children’s books for me, and it allowed me to see this genre as having the potential to create social change.

One of the biggest personal challenges that América faces is feeling like she does not belong. As an undocumented student in an ESL classroom, her fear is reaffirmed by her teachers:

Yesterday as [América] passed Miss Gable and Miss Williams in the hallway, she heard Miss Gable whisper, “She’s an illegal.” How can that be—how can anyone be illegal! She is Mixteco, an ancient tribe that was here before the Spanish, before the blue-eyed, even before this government that now calls her “illegal.” How can a girl called América not belong in America? (n.p)

América’s genuine question signals a history of systemic oppression demarcating who gets to belong and who is excluded from the American imaginary. By tracing her indigenous roots, América seeks to challenge who can lay claim to the land her teachers wish to erase her from. Upon first reading Rodríguez’s book, I found América’s question rather painful. Even though América is a child, her teachers have no qualms about criminalizing and excluding her. At nine years old, there is very little that América can do to challenge her teachers’ ignorance and discrimination; however, the tension in the classroom shifts when Mr. Aponte, a Puerto Rican poet, visits America’s class. Mr. Aponte encourages the class to write poetry about what they know and in whatever language they feel comfortable. América writes about Oaxaca and shares her poetry with her family. Eventually, her mother and younger siblings take part in writing. At the end of the book, Ms. Gable gives América a high mark on one of her poems, which brings great joy to América and her family.

While América remains undocumented at the end of the story, she finds that her poetry gives her a sense of belonging that she did not feel at the beginning. She says: “A real poet. That sounds good to the Mixteca girl, who some people say doesn’t belong here. A poet, América knows, belongs everywhere” (n.p.). Writing has given America a way to challenge and transform the oppressions around her. Her poetry serves as a voice and power that she lacked and has since shared with her family. When I teach this book, I am very careful about talking about the conclusion as the “happy ending.” Instead, I encourage my students to read this moment as part of América’s healing process. Leaving the book with the assumption that everything works out for América is a disservice to the book and those like it. The fears and perils of immigration do not go away because América learned to write poetry. Instead, what she has learned is a set of skills that will help her express how immigration impacts her identity and will help her challenge a system that seeks to exclude her. Reading the ending as a moment in a much larger healing process instead of a resolution further allows me to demonstrate how Latina/o kids lit can transform the lives of Latina/o children and young adults.

If a book like América is Her Name had been available to me as a child, I can imagine it having made a real difference. Feeling excluded or not belonging is a very common theme within traditional coming-of-age stories. However, those feelings become rationalized as “growing pains” or generalized as “everyone feels left out,” or they become a lesson on “not everyone is going to like you.” These motifs often learned in mainstream coming of age stories and in common (mis)understandings of American childhood do not capture América’s experience. América is excluded for specific political and historical reasons. If she were a real child, she will probably be excluded her entire life because she is an (im)migrant. Even if she were to gain legal citizenship, someone will someday ask her “where are you from?” and assume that she does not belong. When I talk about Latina/o children’s books as having the potential to heal, I mean it in reference to these specific moments of exclusion and violence that unfortunately are a reality for Latina/o children. How do we teach our children to answer questions like “where are you from?” or to respond to comments like “you don’t look American”? How do we make them feel like they belong when the world around them may be telling them otherwise? Latina/o children’s literature does not have all of the answers but it is creating conversations on the topics that still require much attention.

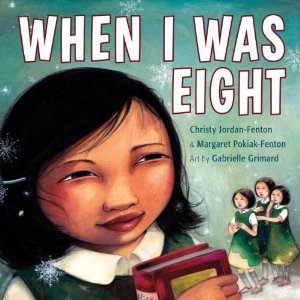

Other Latina/o children’s books with immigration as a theme:

Sonia Alejandra Rodríguez has been an avid reader since childhood. Her literary world was first transformed when she read Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless me, Última as a high school student and then again as a college freshman when she was given a copy of Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street. Sonia’s academic life and activism are committed to making diverse literature available to children and youth of color. Sonia received her B.A. in English from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is currently a PhD candidate at the University of California, Riverside, where she focuses her dissertation on healing processes in Latina/o Children’s and Young Adult Literature.

Sonia Alejandra Rodríguez has been an avid reader since childhood. Her literary world was first transformed when she read Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless me, Última as a high school student and then again as a college freshman when she was given a copy of Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street. Sonia’s academic life and activism are committed to making diverse literature available to children and youth of color. Sonia received her B.A. in English from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She is currently a PhD candidate at the University of California, Riverside, where she focuses her dissertation on healing processes in Latina/o Children’s and Young Adult Literature.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Juanita lives in New York and is Mexican. Felipe lives in Chicago and is Panamanian, Venezuelan, and black. Michiko lives in Los Angeles and is Peruvian and Japanese. Each of them is also Latino.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Juanita lives in New York and is Mexican. Felipe lives in Chicago and is Panamanian, Venezuelan, and black. Michiko lives in Los Angeles and is Peruvian and Japanese. Each of them is also Latino.

After you sign a publishing agreement, whether it’s your first book or tenth, you immediately start to consider your marketing strategy. What people don’t tell you upfront is that you are about to embark on a crazy adventure of ups and downs, sometimes more downs than ups, and you’ll find yourself overwhelmed, exhausted, and maybe even depressed.

After you sign a publishing agreement, whether it’s your first book or tenth, you immediately start to consider your marketing strategy. What people don’t tell you upfront is that you are about to embark on a crazy adventure of ups and downs, sometimes more downs than ups, and you’ll find yourself overwhelmed, exhausted, and maybe even depressed.