by Jacqueline Jules

Jacqueline Jules’ family in 1956

In my small Virginia town, like many places in the 1960s south, the first question people asked upon meeting was “What church do you go to?”

As a child, I remember fielding that question from parents of new friends and hearing my mother answer it in grocery stores.

“We’re Jewish,” I would explain politely. “We go to a synagogue.”

The response was generally a startled one. People would stare like I was a new species at the zoo.

“Oh my! I don’t think I’ve ever met a Jewish person before!”

From there, I’d often have to answer a series of questions about my “Jewish Church.”

I had been taught from a young age that I represented my religion. If I was impolite, all Jews would be considered rude. I had to be on my best behavior at all times so that others would not have a reason to dislike Jewish people. On many occasions, I also had to explain why Jews didn’t believe in Jesus and why I wasn’t terrified of going to hell. And the questions were just as likely to come from adults as other children.

Growing up, Christmas and Easter were never seasons of joy for me. They were times when the questions intensified. Why didn’t I celebrate Christmas? Didn’t the Jews kill Jesus? I learned early on that the Christmas spirit did not extend to Jewish children.

To add to my stranger status, my parents were not Southern born. Mom was a Northerner from Rochester, New York. Dad was from Switzerland and spoke with a thick German accent. He came to the US after World War II and was not a citizen when I was born. His name was Otto. In small-town Southern culture, having foreign roots set my family apart even in our tiny Jewish community.

So feelings of being “different” are quite familiar to me. I know what it is like to be the child of an immigrant. To be embarrassed in public when people ask your father to repeat something three times because they can’t understand what he is saying. To hear a parent talk of a homeland missed deeply. To long for relatives abroad who were only a part of our lives through letters and very occasional visits. To feel alone, apart from others who are comfortable in their skin and their surroundings.

Years later, when I took a position as a librarian in an elementary school with a large immigrant population, I identified with my students immediately. I had watched my own father struggle with the English language, which he learned in adulthood, at age 32. To his credit, he became quite fluent, but he still made some mistakes with grammar and pronunciation. Misunderstandings occurred in family conversations when my father did not understand a nuance or a cultural reference. Or we didn’t understand the perspective he was coming from. He didn’t approve of everything American. I recall what fun he made of sliced white bread which he compared to eating a sponge, and how excited he was when we found bakeries that sold French bread. And I remember how much my father hated turkey. He thought it tasted dry and he insisted my mother serve lamb or duck on Thanksgiving. I also remember that he didn’t care for pumpkin pie. In his mind, pies should be filled with fruit, gooseberries in particular.

The first Thanksgiving I taught at Timber Lane Elementary, a Title I school in Fairfax County, Virginia, I noticed right away that my immigrant students were not interested in my Thanksgiving lessons. Up until then, my story times had been received warmly. Seeing that my English-language learners enjoyed repetitive songs and choruses, I had quickly adopted them into my curriculum. My students had enjoyed songs about animals, the seasons, the five senses, etc. Why did they hate my turkey songs?

A student gently explained: “We don’t have that kind of Thanksgiving dinner in my house.” Suddenly, I stopped being a teacher and returned to my own childhood, where I had been informed that turkey and pumpkin pie were the correct meal choices. These memories led to my first book with Albert Whitman Publishers, Duck for Turkey Day, about young Tuyet, who is worried that her Vietnamese-American family is breaking the rules for Thanksgiving. While the emotions of this book belong to my own childhood, they were deeply shared by the kids I taught. Making my characters Vietnamese-American gave me the opportunity to show how much I identified with my students, along with the universality of the problem. It also made my story current. My experiences as a Jewish child of a German-Swiss in the 1960s south are historical now. While I have shared my Jewish heritage in many of my books, I don’t want everything I write to be limited to my own particular, and not necessarily, universal experiences. Growing up as an outsider myself has naturally made me empathetic to other minorities in America. And it has made me downright indignant that so few children’s books reflect the lives of children who are not white, Christian, and middle-class.

A student gently explained: “We don’t have that kind of Thanksgiving dinner in my house.” Suddenly, I stopped being a teacher and returned to my own childhood, where I had been informed that turkey and pumpkin pie were the correct meal choices. These memories led to my first book with Albert Whitman Publishers, Duck for Turkey Day, about young Tuyet, who is worried that her Vietnamese-American family is breaking the rules for Thanksgiving. While the emotions of this book belong to my own childhood, they were deeply shared by the kids I taught. Making my characters Vietnamese-American gave me the opportunity to show how much I identified with my students, along with the universality of the problem. It also made my story current. My experiences as a Jewish child of a German-Swiss in the 1960s south are historical now. While I have shared my Jewish heritage in many of my books, I don’t want everything I write to be limited to my own particular, and not necessarily, universal experiences. Growing up as an outsider myself has naturally made me empathetic to other minorities in America. And it has made me downright indignant that so few children’s books reflect the lives of children who are not white, Christian, and middle-class.

All too often, books with non-majority characters portray their lives as a situation requiring great explanation. As a young Jewish mother in the 1980s, I was annoyed that most Jewish holiday books described traditions in such detail, they read like nonfiction. Not every Christmas story describes the Nativity. Most Easter stories are about bunnies, not the Resurrection. Why can’t Jewish children have light-hearted picture books that celebrate the joy of their culture, too?

And why can’t children of color have books, particularly easy readers, where they see themselves enjoying life? Why is minority status always the problem in a story rather than just one facet of a particular person’s existence? In my Zapato Power books, a chapter book series about a boy with super-powered purple sneakers, the main character, Freddie Ramos, is Latino. He lives an urban apartment life in a close-knit immigrant community, just like most of the students I taught. But that is not the plot of his stories. Freddie is mostly concerned with how he will solve mysteries and be a hero with his super speed. And in my new series, Sofia Martinez, my main character is a spirited Latina who wants more attention from her large, loving family. I taught many Sofias. Her family eats tamales at Christmas. She uses Spanish phrases in her conversations. And she deserves to learn to read with books that show her family life as fun and normal, not a particular ethnic challenge to be overcome.

And why can’t children of color have books, particularly easy readers, where they see themselves enjoying life? Why is minority status always the problem in a story rather than just one facet of a particular person’s existence? In my Zapato Power books, a chapter book series about a boy with super-powered purple sneakers, the main character, Freddie Ramos, is Latino. He lives an urban apartment life in a close-knit immigrant community, just like most of the students I taught. But that is not the plot of his stories. Freddie is mostly concerned with how he will solve mysteries and be a hero with his super speed. And in my new series, Sofia Martinez, my main character is a spirited Latina who wants more attention from her large, loving family. I taught many Sofias. Her family eats tamales at Christmas. She uses Spanish phrases in her conversations. And she deserves to learn to read with books that show her family life as fun and normal, not a particular ethnic challenge to be overcome.

Many authors say they write the books they would have liked to see as a child. I do that. But I also write stories I wish I had been able to give my students when I taught—books that show it is okay to be who you are.

Jacqueline Jules is the award-winning author of 30 books, including No English, Duck for Turkey Day, Zapato Power, Never Say a Mean Word Again, and the recently released Sofia Martinez series. After many years as a librarian and teacher, she now works full-time as an author and poet at her home in Northern Virginia. Find her on Facebook and at her official author site.

As a reader of this blog, you know what we’re up against. Nearly 5,000 children’s and YA books were published in 2012, but only 1.5% of those titles featured Latin@s. Given the historical inequities our community has faced—which have resulted in our kids’ educational struggles, low average reading level, and high drop-out rate—it is more important than ever that children of diverse cultural backgrounds have access to books in which they see themselves reflected.

As a reader of this blog, you know what we’re up against. Nearly 5,000 children’s and YA books were published in 2012, but only 1.5% of those titles featured Latin@s. Given the historical inequities our community has faced—which have resulted in our kids’ educational struggles, low average reading level, and high drop-out rate—it is more important than ever that children of diverse cultural backgrounds have access to books in which they see themselves reflected. Our first title will be Heartbeat of the Soul of the World, a new short-story collection by René Saldaña, Jr., author of books such as The Jumping Tree and The Whole Sky Full of Stars. A vital book that explores the ins and outs of Latin@ adolescence along the border, Heartbeat is a flagship publication that encapsulates the values and mission of Juventud Press.

Our first title will be Heartbeat of the Soul of the World, a new short-story collection by René Saldaña, Jr., author of books such as The Jumping Tree and The Whole Sky Full of Stars. A vital book that explores the ins and outs of Latin@ adolescence along the border, Heartbeat is a flagship publication that encapsulates the values and mission of Juventud Press.

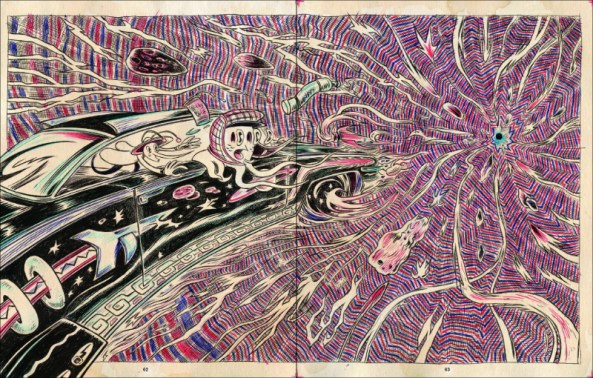

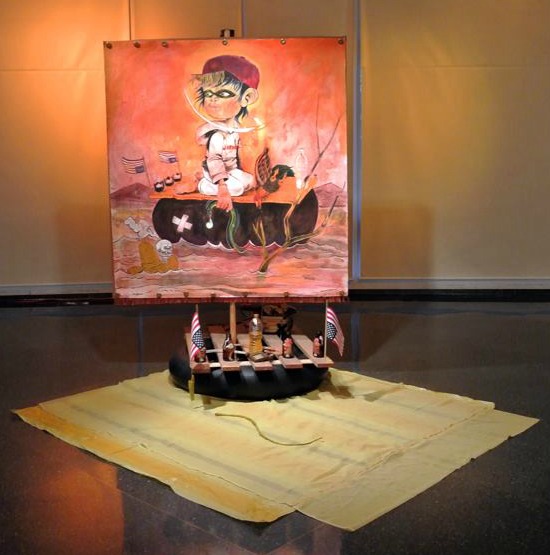

As important as it is to contest happy endings, it is also important to protect Latino children’s right to happiness. I became more aware of this significance upon giving a presentation on Juan Felipe Herrera’s Super Cilantro Girl where I was asked if the story’s ending undermined Esmeralda’s agency. Super Cilantro Girl tells the story of Esmeralda Sinfronteras and her transformation into a giant green superhero set to rescue her mother from an ICE detention center. Upon learning that her mother has been detained at the border, Esmeralda taps into the power of cilantro and gradually changes into Super Cilantro Girl. Bigger than a bus, taller than a house, and with the power of cilantro and flight, Esmeralda breaks her mother out of the detention center and brings her home. Super Cilantro Girl disrupts the anti-immigration policies that seek to separate her family by becoming bigger, stronger, and more heroic than the system. At the end of the story, however, it turns out that Esmeralda was dreaming and did not change into Super Cilantro Girl nor did she rescue her mother. Despite that, though, Esmeralda’s mother returns. In my presentation, I claimed that Esmeralda’s transformation exemplified how the body can be a site of healing. What does the ending then suggest about Esmeralda’s healing process and agency if her transformation into a superhero was just a dream? It was then suggested that I’d have a more productive reading of Super Cilantro Girl if I talked about it as magical realism and/or science fiction.

As important as it is to contest happy endings, it is also important to protect Latino children’s right to happiness. I became more aware of this significance upon giving a presentation on Juan Felipe Herrera’s Super Cilantro Girl where I was asked if the story’s ending undermined Esmeralda’s agency. Super Cilantro Girl tells the story of Esmeralda Sinfronteras and her transformation into a giant green superhero set to rescue her mother from an ICE detention center. Upon learning that her mother has been detained at the border, Esmeralda taps into the power of cilantro and gradually changes into Super Cilantro Girl. Bigger than a bus, taller than a house, and with the power of cilantro and flight, Esmeralda breaks her mother out of the detention center and brings her home. Super Cilantro Girl disrupts the anti-immigration policies that seek to separate her family by becoming bigger, stronger, and more heroic than the system. At the end of the story, however, it turns out that Esmeralda was dreaming and did not change into Super Cilantro Girl nor did she rescue her mother. Despite that, though, Esmeralda’s mother returns. In my presentation, I claimed that Esmeralda’s transformation exemplified how the body can be a site of healing. What does the ending then suggest about Esmeralda’s healing process and agency if her transformation into a superhero was just a dream? It was then suggested that I’d have a more productive reading of Super Cilantro Girl if I talked about it as magical realism and/or science fiction.

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK (from

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK (from

By

By  Fontenot

Fontenot