By Lettycia Terrones

On a bright, 108º F. Las Vegas afternoon, inside the cavernous decadence of Caesars Palace, audience members attending the 2014 Pura Belpré Award Celebración were treated to a gem of a speech by this year’s Pura Belpré Illustrator Award winner, Yuyi Morales. Recognized for her outstanding book, Niño Wrestles the World, Yuyi’s acceptance speech affirmed the resilient strength of children and their power of imagination. Her words served as a reminder to all educators of the important charge we have to provide our children with stories that accurately portray their worlds and strengths.

Since 1996, the Pura Belpré Award has annually recognized Latin@ writers and illustrators for excellence in children’s literature that “best portrays, affirms, and celebrates the Latino cultural experience.” This year’s winner for illustration, Niño Wrestles the World, does just this by capturing –through story, rhythm, and images— the intangible ingredients that come together to form a uniquely Chicano-Latino flavor that any child growing up in East Los Angeles or El Paso will immediately recognize.

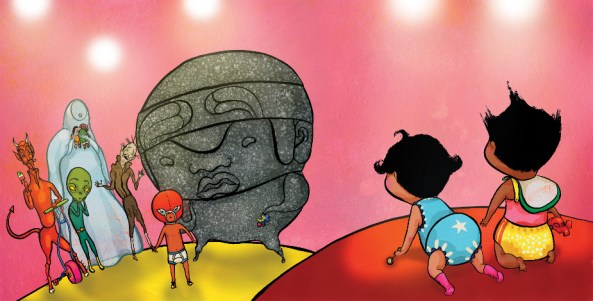

What are these ingredients? La Llorna. El Chamuco. El Extraterrestre. La Cabeza Olmeca. Las Momias. These are the protagonists that star in countless cuentos told and re-told in Mexican and Chicano families. Yuyi presents a dynamic cuento of a boy-hero in a wrestling mask, un niño luchador, who through wit, humor, ganas, and family teamwork, outsmarts these terrifying figures of Mexican and Chicano cultural mythology. As Yuyi reminded us in her acceptance speech, children’s imaginative capacity is an empowering tool that enables them to confront life situations with positive resilience. In addition to her prepared remarks, Yuyi described her own imaginative process as a child, where she was able to transform the often scary and mysterious cultural myths of La Llorona and El Chamuco into figures she could contend with and, perhaps most importantly, learn to play with.

What are these ingredients? La Llorna. El Chamuco. El Extraterrestre. La Cabeza Olmeca. Las Momias. These are the protagonists that star in countless cuentos told and re-told in Mexican and Chicano families. Yuyi presents a dynamic cuento of a boy-hero in a wrestling mask, un niño luchador, who through wit, humor, ganas, and family teamwork, outsmarts these terrifying figures of Mexican and Chicano cultural mythology. As Yuyi reminded us in her acceptance speech, children’s imaginative capacity is an empowering tool that enables them to confront life situations with positive resilience. In addition to her prepared remarks, Yuyi described her own imaginative process as a child, where she was able to transform the often scary and mysterious cultural myths of La Llorona and El Chamuco into figures she could contend with and, perhaps most importantly, learn to play with.

This transformative power demonstrates the enormous agency children have to make meaning in the world. It depicts what Dr. Tara Yosso points to in her seminal work on cultural wealth and social capital, which she calls Community Cultural Wealth. Community Cultural Wealth lists specific assets practiced and nurtured in communities of color, which serve as forms of resistance to the myriad social oppressions marginalized people contended with daily. Emerging from the cultural knowledge passed down in families and communities, these assets include “aspirational, navigational, social, linguistic, familial and resistant capital.”

Yuyi’s book exemplifies Community Cultural Wealth at work. Its text and illustration display the wealth of linguistic storytelling traditions of cuentos handed down in our families. It also serves as a meta-narrative of resistance through its prominent use of Mexican and Chicano cultural images. Yuyi’s narrative and illustration authentically capture how, for instance, the myth of La Llorona is in continuous transformation as she is imagined by our children today. Instead of becoming clichéd tropes of Mexican and Chicano culture, El Chamuco, El Extraterrestre, La Cabeza Olmeca, and Las Momias, are represented authentically as living and changing stories. This truly is a marker of Yuyi’s outstanding mastery of the picture book. She brings to the world of children’s literature works that defy cultural stereotypes, and that champion children as creative, imaginative meaning-makers.

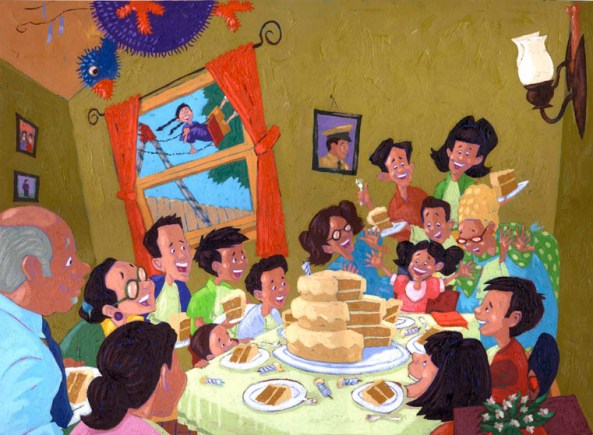

I thought a lot about the impact of Yuyi’s Niño Wrestles the World when I attended a Lucha Libre Night at the East Los Angeles Community Youth Center last spring. The family-run event brought in masked luchadores from Tijuana and Los Angeles to battle it out in the recreation center’s well-worn boxing ring. At the halftime marker, the ring became open for the many kids in attendance to frolic with abandon and take photos with the night’s Lucha Libre heroes. I thought about how for many children living in underserved communities, Yuyi’s story of the boy-hero, the niño luchador, is an actual and accurate depiction of their lives. I wondered how many of the kids in attendance that night had been exposed to Niño Wrestles the World in their classroom or public library. I wondered how this exposure would strengthen their sense of belonging and reflect back to them their self-efficacy.

Educators should remember the characters brought to life in Yuyi’s picture book are still very much alive today in the imaginations of Latino children. They are stories that form an essential cultural fabric of what it means to be Mexican and/or Chicano. Whether we call our people first-generation, second-generation, or if we are from generations that preceded the Treaty of Guadalupe, or are present-day refugee generations embarking on perilous journeys, climbing atop trains and traversing deserts, to seek our families and a promise of a better future in the United States. These stories are ours. They form an American story.

References

Pura Belpré Award

http://www.ala.org/alsc/awardsgrants/bookmedia/belpremedal

Yosso*, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69-91.

Yuyi Morales, Illustrator Award Acceptance Speech, page 4 http://www.ala.org/alsc/sites/ala.org.alsc/files/content/awardsgrants/bookmedia/belpre-14.pdf

Lettycia Terrones, M.L.I.S., serves as the Education Librarian at the Pollak Library at California State University, Fullerton. Her research interests are in Chicana/o children’s literature and critical literacy. Lettycia is an American Library Association Spectrum Scholar and a member of REFORMA: The National Association to Promote Library & Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish Speaking.