by Cecilia Cackley

by Cecilia Cackley

Juana Medina’s latest book is Juana and Lucas, published this September by Candlewick Books. An illustrated early chapter book, it is narrated by Juana, a little girl living with her dog Lucas in Bogotá, Colombia, who gives the reader a tour of her city and her life. Juana loves her family, her friends and her school, but she does not like having to learn English. Only when her family reminds her that they have a trip planned to the theme park Astroland in the United States, does Juana admit that maybe English has its uses after all.

Medina was born in Colombia and now lives in Washington, DC, where she works out of a shared studio space on the northwest side of the city. I spent an afternoon with her there, looking at the tools she used to create the illustrations for Juana and Lucas and talking about the process of creating the book.

Medina started out working in graphic design. She originally came to the United States from Colombia to study at the Corcoran School in DC, but found that the program there didn’t fit her needs and instead she moved to the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Her study of graphic design prepared Medina to write and illustrate this story. “It gave me great structure to understand books,” she says, adding that studying alongside undergrad students “made it more fun, gave it a sense of exploration.”

That sense of exploration is on full display in Juana and Lucas, which features a loose, sketchy quality to the ink drawings. Medina points to the British illustrator Quentin Blake as a key influence, noting that he draws with both hands, and she often does too, or sometimes draws with one hand and colors with the other. Another favorite artist is Joaquin Salvador Lavado, better known by his pen name Quino, who created the iconic comic strip Mafalda for the Argentine newspaper El Mundo. Medina gushes about Quino’s “level of expressiveness.” She points out: “He includes wit in such simple traces and achieves complexity and an incredible level of detail in just a few lines.”

That sense of exploration is on full display in Juana and Lucas, which features a loose, sketchy quality to the ink drawings. Medina points to the British illustrator Quentin Blake as a key influence, noting that he draws with both hands, and she often does too, or sometimes draws with one hand and colors with the other. Another favorite artist is Joaquin Salvador Lavado, better known by his pen name Quino, who created the iconic comic strip Mafalda for the Argentine newspaper El Mundo. Medina gushes about Quino’s “level of expressiveness.” She points out: “He includes wit in such simple traces and achieves complexity and an incredible level of detail in just a few lines.”

Medina likes the ability to switch between different artistic media from book to book. For her, it’s about what the story asks for. Juana and Lucas is illustrated in pen and ink, and colored with watercolor, which is a very personal medium for Medina, as it reminds her of childhood and illustrations by favorites such as Quentin Blake. The personal components of the story of Juana and Lucas meant that watercolor felt right for the book, because it gives it a sense of nostalgia. Other illustration projects that Medina has worked on, such as Smick, written by Doreen Cronin, and the counting book 1 Big Salad combine found objects with digital drawings.

For Juana and Lucas, Medina experimented with sketches in pencil first, then used a light box to draw the final version of each illustration in ink. Watercolor came next and the drawing was then scanned so that the colors could be adjusted digitally. This process also allowed Medina to correct small errors without having to redraw an entire composition. She showed me one spread containing an airplane that hadn’t been in the original sketch. Later in the process, it was added digitally to cover up an unruly inkblot!

For Juana and Lucas, Medina experimented with sketches in pencil first, then used a light box to draw the final version of each illustration in ink. Watercolor came next and the drawing was then scanned so that the colors could be adjusted digitally. This process also allowed Medina to correct small errors without having to redraw an entire composition. She showed me one spread containing an airplane that hadn’t been in the original sketch. Later in the process, it was added digitally to cover up an unruly inkblot!

For Juana and Lucas, her first chapter book, Medina wrote the story first, and then went back to draw. Through writing and rewriting, she found the balance between word and image. She says “It’s important to make a book where even if a kid can’t read yet, they can still get a sense of the story.” The relationship between Juana and Lucas, in particular, is mostly visual, so even if Juana isn’t talking about him very much in the text, you see them interacting in the illustrations. Medina points out that this is more realistic, as our interactions with our pets are mostly visual and tactile. Having narrative both in the text and in the illustrations makes this a great choice for readers still transitioning from picture books to chapter books.

The dynamic presentation of text (words that curve, get bigger or in other ways deviate from the standard type) featured throughout the story was Medina’s idea. Her thinking is that typography is part of language, explored, and it can cue certain meanings of words that may be unfamiliar to young readers.

The dynamic presentation of text (words that curve, get bigger or in other ways deviate from the standard type) featured throughout the story was Medina’s idea. Her thinking is that typography is part of language, explored, and it can cue certain meanings of words that may be unfamiliar to young readers.

Medina says about her writing process: “I was telling a story that was personal in my second language, so that was hard. I was lucky to be working with an editor who got it—figuring out the exact language to make it understandable without imposing too much. Candlewick has been great at not treating the text as precious, but instead seeing what is working and what isn’t.”

The book was written first in English, and she says it was almost like writing lyrics, choosing places where Spanish could be inserted in a way that made sense. Medina wanted to avoid echoing the English words in Spanish. She felt it was important to be respectful of readers and give them a chance to figure out the meanings of the Spanish words on their own. Its inclusion adds richness and reminds the reader that English isn’t Juana’s first language. The mix of the two languages feels very genuine, because mixing languages happens with all multilingual children. Their brains are trying to figure it out, and it’s natural for them to begin a sentence in one language and end it in another. The Spanish hasn’t deterred young readers who aren’t already familiar with the language. According to Medina, “I gave it to my niece, who was the first kid to ever read it. She doesn’t speak Spanish, but as soon as she finished the book, she went to the computer and pulled up Google Translate. After a moment she turned to me and said, ‘Me encantó tu libro,’ which was just…I was crying.”

For readers in the United States used to seeing European cities such as London or Paris in children’s literature, it’s a breath of fresh air to get such a detailed, child’s-eye view of a major South American city. Medina went back to Bogotá after writing several versions, and says the trip was bittersweet. “It was the first time there without my grandparents, without having a place there to call home. It was a difficult trip, but it was sweet to see the mountains and smell the eucalyptus, and it was validating to see everything. I took some license in the book. I’m not tying myself to fact-checking everything, which was liberating in a way. There was a lot I left out, especially surrounding the conflict and civil war I grew up with. That’s something I’ll maybe address in another book. The hardest illustration was my grandparents’ house, which no longer exists. It was a safe haven, so no illustration could truly do it justice.”

For readers in the United States used to seeing European cities such as London or Paris in children’s literature, it’s a breath of fresh air to get such a detailed, child’s-eye view of a major South American city. Medina went back to Bogotá after writing several versions, and says the trip was bittersweet. “It was the first time there without my grandparents, without having a place there to call home. It was a difficult trip, but it was sweet to see the mountains and smell the eucalyptus, and it was validating to see everything. I took some license in the book. I’m not tying myself to fact-checking everything, which was liberating in a way. There was a lot I left out, especially surrounding the conflict and civil war I grew up with. That’s something I’ll maybe address in another book. The hardest illustration was my grandparents’ house, which no longer exists. It was a safe haven, so no illustration could truly do it justice.”

Readers will be happy to learn that Medina is already working on a second book in the Juana and Lucas series. In addition, her follow up to 1 Big Salad, an ABC book called ABC Pasta, will be out in the spring from Penguin Random House. Medina’s advice to other Latinx artists looking to break into illustration is to be persistent and disciplined about their work. “Tell your own stories,” she says “Not the ones that will simply please an audience, but the ones that are meaningful.” And like her character Juana, struggling to balance her two languages, Medina advises artists to “find the language for the story you want to tell.”

Juana Medina is a native of Colombia, who studied and taught at the Rhode Island School of Design. Her illustration and animation work have appeared in U.S. and international media. Currently, she lives in Washington, DC, and teaches at George Washington University. See more of Juana’s work at her official website.

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at www.witsendpuppets.com.

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at www.witsendpuppets.com.

By Monica Brown

By Monica Brown

mother, a teacher, and a writer who meets thousands of children each year, I’ve also observed the way girls (and boys) who don’t quite “fit in” can experience social exclusion, teasing, and even bullying.

mother, a teacher, and a writer who meets thousands of children each year, I’ve also observed the way girls (and boys) who don’t quite “fit in” can experience social exclusion, teasing, and even bullying. everybody else tells us to be.” He goes on to say, “we should not obey . . . imagination should not comply.” There is such a freedom in being oneself, and that is a gift I bestow on my character Lola. It was a dream and a pleasure to create a smart, diverse, multicultural character who each day chooses to be herself, and whose imagination certainly does not comply! Viva smart, bold girls, and viva Lola!

everybody else tells us to be.” He goes on to say, “we should not obey . . . imagination should not comply.” There is such a freedom in being oneself, and that is a gift I bestow on my character Lola. It was a dream and a pleasure to create a smart, diverse, multicultural character who each day chooses to be herself, and whose imagination certainly does not comply! Viva smart, bold girls, and viva Lola!

Monica Brown, Ph.D. is the author of many award-winning books for children, including

Monica Brown, Ph.D. is the author of many award-winning books for children, including

Joe Jiménez is

Joe Jiménez is

Alarcón, F. (2005). Poems to Dream Together/Poemas para sonar juntos. Illustrations by Paula Barragán. Lee & Low Books.

Alarcón, F. (2005). Poems to Dream Together/Poemas para sonar juntos. Illustrations by Paula Barragán. Lee & Low Books. Tracey Flores is a former English Language Development (ELD) and Language Arts teacher who worked in elementary classrooms for eight years. She currently serves as the director of El Día de los Niños, El Día de los Libros and is a teacher consultant with the Central Arizona Writing Project (CAWP) at Arizona State University (ASU). Currently, Tracey is a PhD Candidate in English Education in the Department of English at ASU. Her research focuses on adolescent Latina girls and mothers’ language and literacy practices and on using family literacy as a springboard for advocacy, empowerment, and transformation for students, families, and teachers. In her free time she enjoys writing, reading Young Adult (YA) literature, drinking coffee, running, practicing yoga and spending time with her 8 month old daughter.

Tracey Flores is a former English Language Development (ELD) and Language Arts teacher who worked in elementary classrooms for eight years. She currently serves as the director of El Día de los Niños, El Día de los Libros and is a teacher consultant with the Central Arizona Writing Project (CAWP) at Arizona State University (ASU). Currently, Tracey is a PhD Candidate in English Education in the Department of English at ASU. Her research focuses on adolescent Latina girls and mothers’ language and literacy practices and on using family literacy as a springboard for advocacy, empowerment, and transformation for students, families, and teachers. In her free time she enjoys writing, reading Young Adult (YA) literature, drinking coffee, running, practicing yoga and spending time with her 8 month old daughter. My husband, Gene, inspired me. I wouldn’t know the first thing about magic if it weren’t for him. He’s an aficionado with a great collection of magic books, props, and videos. Over the years, I’ve been a tagalong at magic lectures and conventions, including the TAOM convention that I write about. Magicians are so creative, and if you think about a magic performance, you’ll realize that it’s just another form of storytelling. How could I resist? I had to write this book! And I had so much fun finding magic tricks that resonated with the characters’ personal lives. This is what stories do—give us tools for coping and for celebrating life.

My husband, Gene, inspired me. I wouldn’t know the first thing about magic if it weren’t for him. He’s an aficionado with a great collection of magic books, props, and videos. Over the years, I’ve been a tagalong at magic lectures and conventions, including the TAOM convention that I write about. Magicians are so creative, and if you think about a magic performance, you’ll realize that it’s just another form of storytelling. How could I resist? I had to write this book! And I had so much fun finding magic tricks that resonated with the characters’ personal lives. This is what stories do—give us tools for coping and for celebrating life.

Marianne Snow Campbell

Marianne Snow Campbell

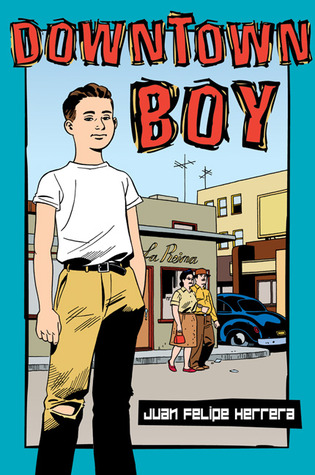

For older students I often refer to Juan Felipe Herrera’s novel in verse Downtown Boy. More often than not, we focus on the young main character Juanito to discuss issues such as discrimination in school, immigration, gender roles, masculinity and femininity, diabetes, family, and more. If I have an opportunity to teach the entire novel, then I often create poetry portfolios with my students where we pick a broader theme like identity, culture, and/or community that will thread throughout all their poems. If I don’t have enough time to cover the entire novel, then I usually pick the poems that will best represent the student population or the poem with which they can connect to the most.

For older students I often refer to Juan Felipe Herrera’s novel in verse Downtown Boy. More often than not, we focus on the young main character Juanito to discuss issues such as discrimination in school, immigration, gender roles, masculinity and femininity, diabetes, family, and more. If I have an opportunity to teach the entire novel, then I often create poetry portfolios with my students where we pick a broader theme like identity, culture, and/or community that will thread throughout all their poems. If I don’t have enough time to cover the entire novel, then I usually pick the poems that will best represent the student population or the poem with which they can connect to the most. Dr. Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez’s research focuses on the various roles that healing plays in Latinx children’s and young adult literature. She currently teaches composition and literature at a community college in Chicago. She also teaches poetry to 6th graders and drama to 2nd graders as a teaching artist through a local arts organization. She is working on her middle grade book. Follow Sonia on Instagram @latinxkidlit

Dr. Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez’s research focuses on the various roles that healing plays in Latinx children’s and young adult literature. She currently teaches composition and literature at a community college in Chicago. She also teaches poetry to 6th graders and drama to 2nd graders as a teaching artist through a local arts organization. She is working on her middle grade book. Follow Sonia on Instagram @latinxkidlit