By Patrick Flores-Scott

#WeNeedDiverseBooks. The trending hashtag is a channel for conversation around the huge problem of a lack of diversity in children’s literature. The problem has been noted in many recent articles and so have the reasons we need more books by diverse authors and books with complex, real diverse characters.

For many years I was lucky to be a public school teacher in very diverse schools. At different points I was both a general education classroom teacher and a reading specialist. As a classroom teacher, I was able to seek and find the books I wanted my class to hear and read. More often than not, these books had main characters of color. I had the time, energy, resources, and relationships that helped me find great books that my students loved.

My students, however, especially my reluctant readers, were not going to work so hard to find a book that would reflect the cultural, racial, socio-economic realities of their community. They were going to pick the available book, the one closest to their hand when it was time to leave the library, or the trendy book that made them look like they were in the reading “know.”

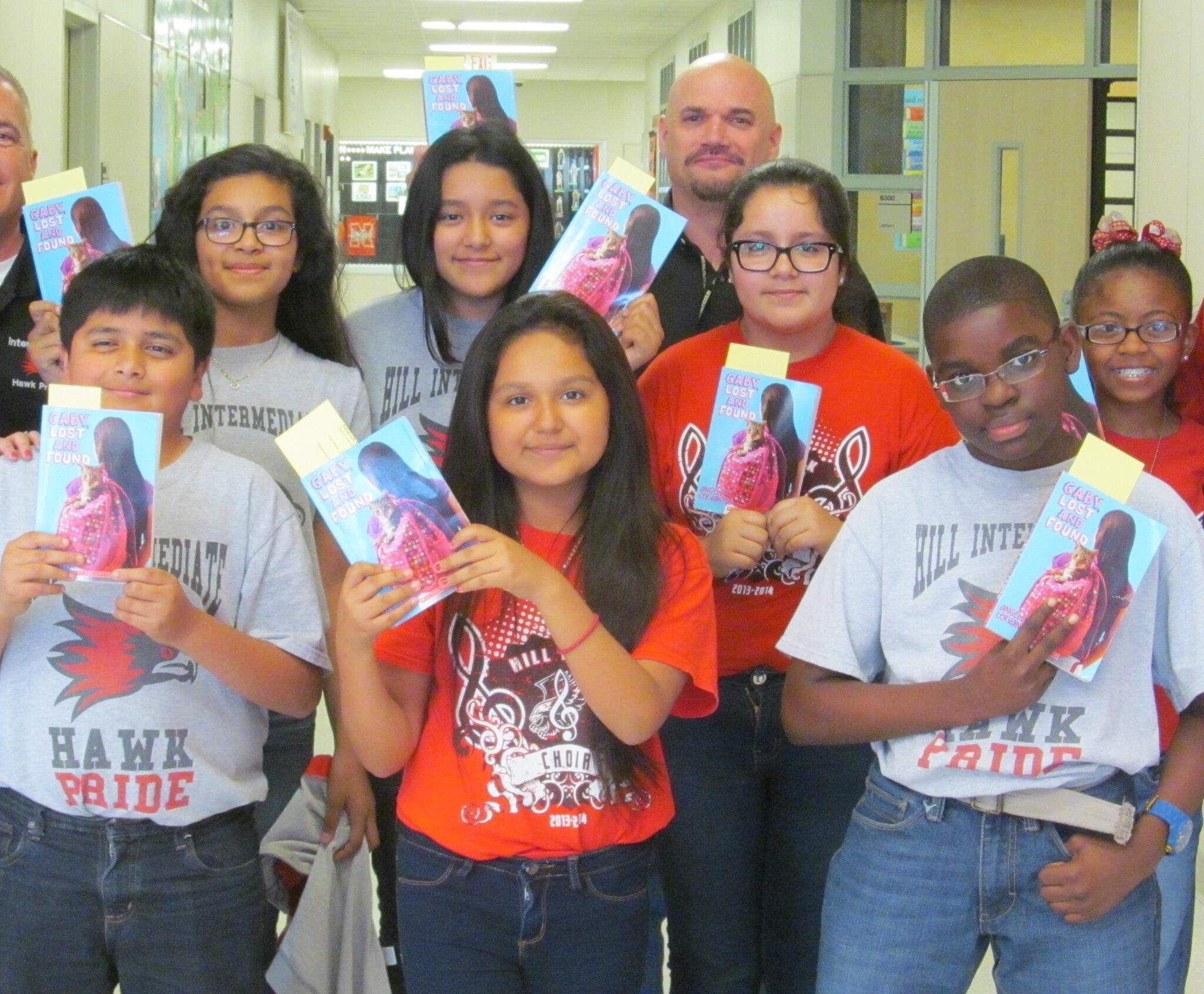

Author Angela Cervantes posted this picture on Twitter during the #WeNeedDiverseBooks Campaign.

Students need to be able to accidentally stumble their way into a great book that reflects their own background or one that opens their eyes to new characters and communities. They shouldn’t have to work for it. They shouldn’t have to fight for it. Kids have enough on their plate. Yes, some students are going to research authors, seek out new books and reading experiences, challenge their school librarian and make demands. Most fifth graders, however, are just struggling to make it through the day. They end up with the default book… and given the math of the situation, they’re going to walk out with another book by a white author with a white main character. Is this a tragedy? In the moment, no. That default book might be a great one. But this scene takes place over and over each day in most schools in the country and that great book–if the student is lucky–may just be another in a long line of books that reinforces the notion that great books are written by white authors and that white kids are the ones worthy of books written about them. This notion is a toxic one, regardless of a student’s background.

Children’s books are a piece of a larger pie. A lack of diversity in film and television reinforces the notion that white stories are more relevant than non-white stories. The make-up the Senate (97 out 0f 100 are white) reinforces the notion that non-whites do not have a role in the highest levels of politics. Yes, there is the President, but his cabinet is made up of 70% white males. Kids see this. They see thousands of African American college athletes and they know that, in the vast majority of cases, these athletes are led to battle by white coaches. They know that the percentages of Black and Latino men in prison are crazily out of proportion with the population of Black and Latino men. Kids see all this. They take it in. The perceptions become realities for them.

My wife and I are the proud, exhausted parents of two rambunctious little boys. Their grandparents are Mexican-American on their mom’s side. My parents are white. My dad is from the U.S., my mom a Spanish-speaking Latina from South America. We will raise our boys to be proud of all that they are and proud of all the Latino, Caucasian, African-American, Asian and mixes of the aforementioned that make up their diverse extended family. While we will do our best to teach that the content of one’s character, not the color of one’s skin (one’s gender, sexual orientation, physical ability) is what is important, television, our political and judicial systems, sports…. And even the make-up of CHILDREN’S BOOKS, will send messages that complicate, skew, and even deem our parental message well-meaning, but just wrong.

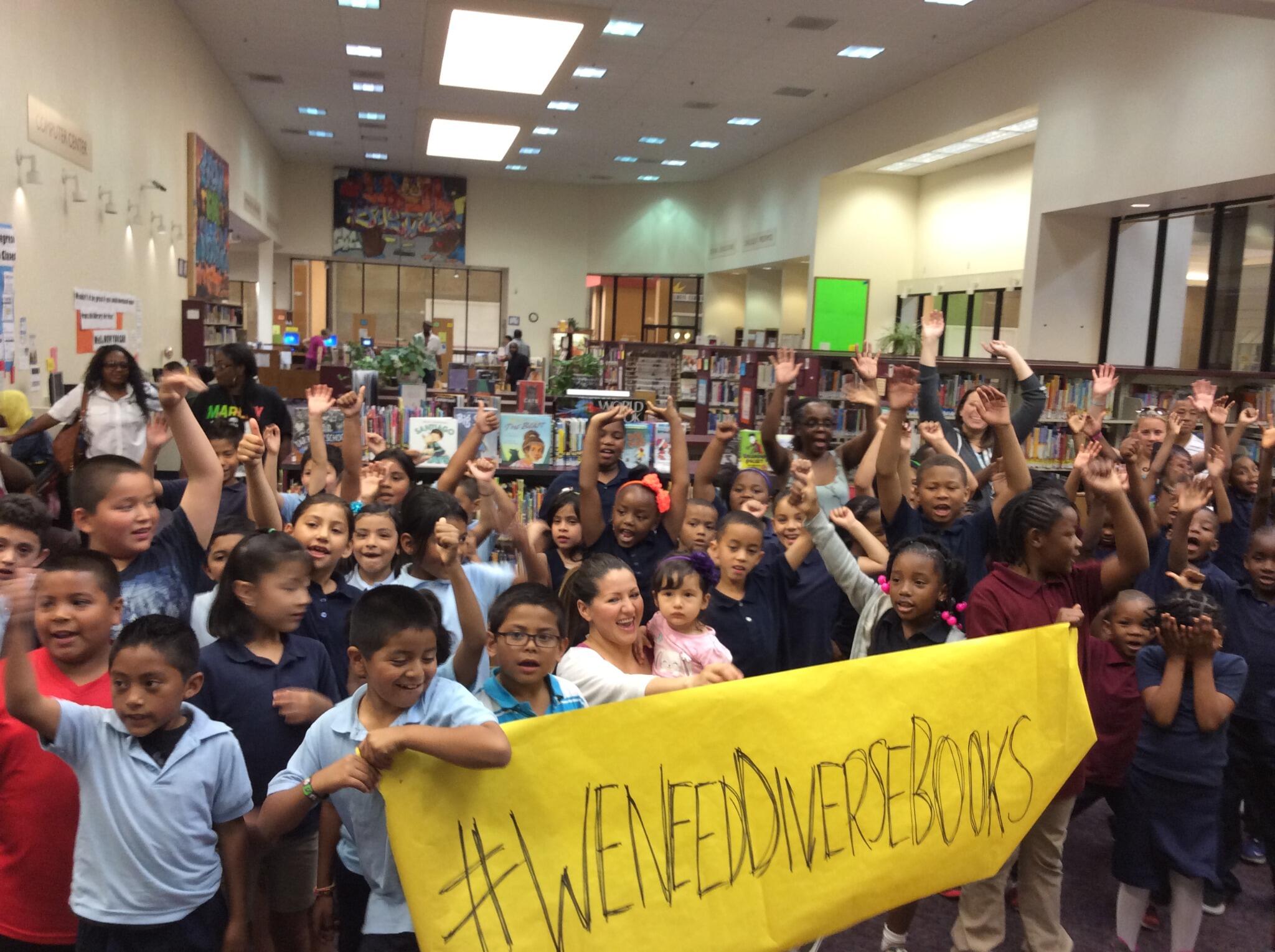

The Oakland Public Library in California posted lots of great pictures like this one on Twitter during the #WeNeedDiverseBooks Campaign.

What do we do about it? The #WeNeedDiverseBooks Movement (Can it please be a movement? We need more movements around here.) is a potentially very important call for change in the children’s book world. Now, we need to push for intentionality. Gatekeepers need to have their feet held to the fire. The Movement (!) needs to push publishers to set goals that trend their books in a more realistically diverse direction. It needs to push the industry to hire editors from diverse backgrounds and to hire and support diverse interns and entry-level assistants who can have the power to move books off the pile and into editors’ hands. The Movement needs to hold publishers accountable.

Institutions which support writers and illustrators, like my beloved SCBWI, need to recruit underrepresented writers to their conferences. (And to check out the percentage of white male panelists and speakers compared to the percentage of white male attendees.) Groups like SCBWI need to be pushed to intentionally foster and mentor a more diverse writing community.

The movement needs to push us published authors of all colors and stripes, to mentor diverse up-and-comers, to include pro-bono school visits to underfunded schools, and to write real, complex, fallible diverse characters who live the entirety of the American experience.

Members of The Movement need to request diverse books at their bookstores and libraries. We need to post reviews on Amazon and Goodreads and library websites. Members of the Movement need to advise book bloggers and to follow and support blogs like this one. We need to give diverse books as birthday presents and to talk about our favorites on the bus, at work, in line at the bookstore…

Members of The Movement need to push our political leaders to support the health, education and welfare of our future readers and writers.

Publishers, agents, bookstore workers, librarians, teachers, authors… there are bunches these folks out there doing the positive stuff that will make change possible. The Movement needs to support them and it needs to push for intentionality in those who mean well, but have not yet made the move to change.

Patrick Flores-Scott was, until recently, a long-time public school teacher in Seattle, Washington. He’s now a stay-at-home dad and early morning writer in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Patrick’s first novel, Jumped In, has been named to a YALSA 2014 Best Fiction for Young Adults book, an NCSS/CBC Notable Book for the Social Studies and a Bank Street College Best Book of 2014. He is currently working on his second book, American Road Trip.

Patrick Flores-Scott was, until recently, a long-time public school teacher in Seattle, Washington. He’s now a stay-at-home dad and early morning writer in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Patrick’s first novel, Jumped In, has been named to a YALSA 2014 Best Fiction for Young Adults book, an NCSS/CBC Notable Book for the Social Studies and a Bank Street College Best Book of 2014. He is currently working on his second book, American Road Trip.

Jumped In was featured in Libros Latin@s on Thursday. Click here to see the overview.

But if you’ll note: in all those books and the hundreds of others I devoured, I never really saw myself, or anyone remotely like me. The majority of characters in books for kids and teens in the ’80s and ’90s were white. And according to Christopher Myers in his recent New York Times piece,

But if you’ll note: in all those books and the hundreds of others I devoured, I never really saw myself, or anyone remotely like me. The majority of characters in books for kids and teens in the ’80s and ’90s were white. And according to Christopher Myers in his recent New York Times piece,

Millennium pop and idolized Harriet the Spy.

Millennium pop and idolized Harriet the Spy. When people say they’re “afraid” they’re not going to give their “Other” character justice by writing from an experience other than an Anglo-American experience, I call bull. It is scary writing about an experience other than yours. However, unless your character has just moved to Kentucky from a remote town in Panama, then why are you afraid to write the experience of an otherwise straightforward character? Your character can still be named Danilo Cordova and the only research you have to do is “What does a teenage boy like?”

When people say they’re “afraid” they’re not going to give their “Other” character justice by writing from an experience other than an Anglo-American experience, I call bull. It is scary writing about an experience other than yours. However, unless your character has just moved to Kentucky from a remote town in Panama, then why are you afraid to write the experience of an otherwise straightforward character? Your character can still be named Danilo Cordova and the only research you have to do is “What does a teenage boy like?”