Have you ever cried in class? I have. And no, I’m not talking about kindergarten. I’m in my 30s, and yes, I shed actual tears during a workshop during my writing for children creative writing MFA program at the New School two years ago.

No, it wasn’t a particularly harsh critique. I have to say, I have an incredibly thick skin. Most of the time.

But this particular workshop was a safe space. Taught by the stunningly smart and super-nurturing Andrea Davis Pinkney, this one focused on a topic too frequently neglected by both the academy and publishing: diversity. Specifically, we were talking about diversity in kidlit and YA, and addressing why it is important.

And though it’s been a long time since I was a kid or even a teenager, the wound was still fresh. Because we still haven’t gotten there.

Growing up as a little brown girl – one of the few, back then – in small-town, suburban central New Jersey, books were my escape. I caused a ruckus alongside little Anne in Avonlea; I mourned Beth along with her sisters in the harsh winter of Maine; I honed my grand ambitions like Kristy and her babysitters’ club; I even swooned alongside Elena over the brothers Salvatore when the Vampire Diaries was originally released. (Yes, I am that old.)

But if you’ll note: in all those books and the hundreds of others I devoured, I never really saw myself, or anyone remotely like me. The majority of characters in books for kids and teens in the ’80s and ’90s were white. And according to Christopher Myers in his recent New York Times piece, “The Apartheid of Children’s Literature,” the majority still are today, by quite a landslide.

But if you’ll note: in all those books and the hundreds of others I devoured, I never really saw myself, or anyone remotely like me. The majority of characters in books for kids and teens in the ’80s and ’90s were white. And according to Christopher Myers in his recent New York Times piece, “The Apartheid of Children’s Literature,” the majority still are today, by quite a landslide.

Why is this worth discussing? Because it hurts. A lot. It’s a hit to a kid’s self-esteem to be told – silently, but oh so clearly – that their story is not worth telling, that their voice is not important.

As Myers notes in his piece, it leaves you with “a gap in the much-written-about sense of self-love that comes from recognizing oneself in a text, from the understanding that your life and lives of people like you are worthy of being told, thought about, discussed and even celebrated.”

Honestly, it’s a punch to the gut. It kills me that, 30 years later, kids are still feeling this way. That my daughter, all of four now and already shaping up to be a voracious reader, will still feel that pinch.

That’s why I cried that day in class. And that’s why, with my writing partner Dhonielle Clayton, whom I met on the first day of my MFA program, I co-founded CAKE Literary, a literary development company that focuses on high concept fiction with a strong commitment to diversity.

I know what you’re thinking: silly thing to bank a personal fortune (however small) on, right? We all know diversity doesn’t sell.

Well, Dhonielle and I would like to call bullshit on that. Done the right way, diversity can bring a richness and flavor to any manuscript. After all, so much about a great read is in the details – the scent and sizzle of freshly-fried samosas wafting up from her mama’s kitchen, the ferocious whip of the wind on an icy February morning, the ashy knees she keeps hidden under too-long skirts, the blush that climbs up her throat and to her cheeks when she flirts with her crush for the first time. The details give texture and color, a sense of time and place and, most importantly, character. The details define worldview and fill out voice.

But the main thing is the big picture – and what our company will do is focus on BIG pictures. Smart, sophisticated storytelling that’s full of flavor – books where the diversity is a major part of the character, but not the central focus of the character.

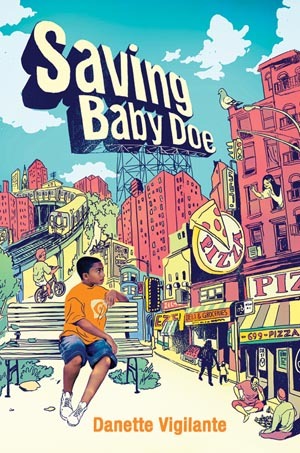

Case in point: our debut novel, Tiny Pretty Things, which is due next summer. Set in a cutthroat New York City ballet academy, the book centers on three characters, one white, one black, and one half-Korean. And while their backgrounds definitely inform the characters’ worldviews and experiences, the book is not about skin color. It has a plot – a juicy, riveting and ultimately relatable story that we’re hoping will leave readers wanting more.

That’s what we’ll do with each of our projects: tell a fun, delicious story that readers want to read, but incorporate real-life flavor – meaningful diversity – in a natural, relevant way. We’re all about keeping it real, so part of our mission will be to connect vibrant, authentic voices with the stories we’re crafting.

What exactly does CAKE do? We’re not an agency or publisher, but rather a book packager – a YA and middle grade think tank of sorts. We come up with sharp multimedia concepts that we then develop into a detailed outline. Once the idea is fleshed out, we hire a writer to work with us on several chapters or a complete manuscript, which we then package to take to publishers. Once the project sells, the writer stays on board to complete the project. Some book packagers get a bad rap for being notoriously stingy. But CAKE’s aim is to be very writer friendly, because, after all, we’re writers, too. So when we work with a writer on a project, they get paid a flat fee on signing, on delivery, and then, when the project sells, they get a cut of those proceeds as well. The other thing that sets CAKE apart is our commitment to diversity, which is an integral part of every CAKE project.

Interested in learning more? We’ll be looking to hire writers beginning this spring, so connect with us on CAKELiterary.com or via CakeLiterarySubmissions@gmail.com. You can also follow us on Twitter @CAKELiterary.

AUTHOR:

AUTHOR: