This is an excellent post from Kayla Whaley who has joined our 2014 Reading Challenge. She makes a great point about supporting diversity by choosing to diversify her bookshelves. Saying you support diversity in kid lit is great. Doing something, like reading more books by and about POC, is even better! Thanks for joining us, Kayla!

Category Reading

The Road to Publishing: One Take on Working with a (Rock Star) Editor

In articles and blog posts about breaking into the world of publishing, the lion’s share of attention goes to the writing craft, getting an agent, and securing a book deal. But what happens after those hurdles have been jumped? What can writers expect from their editors once the deal is sealed? And what will editors expect from writers?

Because writer-editor relationships are endlessly varied, I don’t actually have the answers to these questions. In fact, as I started writing this post, I realized that the only thing I am really qualified to talk about are my experiences working with Andrew Karre, my editor at Carolrhoda Lab. Andrew bought my first two novels, What Can’t Wait and The Knife and the Butterfly, in a two-book deal back in 2009, and now I am in the beginning stages of working with Andrew on a third novel. I can’t say what it’s like for other writers, although you can find some descriptions of authors’ experiences with editors, my favorite being the five perspectives offered up here.

Because writer-editor relationships are endlessly varied, I don’t actually have the answers to these questions. In fact, as I started writing this post, I realized that the only thing I am really qualified to talk about are my experiences working with Andrew Karre, my editor at Carolrhoda Lab. Andrew bought my first two novels, What Can’t Wait and The Knife and the Butterfly, in a two-book deal back in 2009, and now I am in the beginning stages of working with Andrew on a third novel. I can’t say what it’s like for other writers, although you can find some descriptions of authors’ experiences with editors, my favorite being the five perspectives offered up here.

For the editor’s perspective, check out this post from Scholastic imprint editor Cheryl Klein, who also has a book on editing YA. Andrew will stop by the blog on Thursday to toss in his two cents on editorial work; if you want to balance some of my gushing below with more objective reporting, you can read this feature on him in Publisher’s Weekly.

Enough preliminaries. Here’s the scoop I can offer on working with my editor.

What happens after you sign the contract with a publisher? Waiting. Waiting. Waiting. I remember expecting to hear from Andrew the day after the contract was signed, but often there’s a considerable lag (months, friends) between sealing the deal and getting the feedback that will guide the revision. Editors are working on dozens of projects—all in different stages—at any given point. The good ones are expert at juggling these demands and giving each project what it needs.

Isn’t it painful to be told how to revise? To start with, I have to say that Andrew is as close to my “ideal reader” as I expect ever to find. With all three novels, he has grasped the essential aspects of the projects as well as (or better than) I did myself. This fact secures my total confidence in his intuition and editorial recommendations; on top of that, I’ve benefitted from his ability to see subterranean connections that invited development as well as other missed opportunities. So even what might have been “pain” in the process invariably felt crucial to the mission of making the book what it was meant to be.

I should also say that the thought of revision is what gets me through the agony of drafting; revision is my happy zone, where things finally come together. I don’t mind cutting scenes or paragraphs or sentences that I love. I don’t mind writing new material. I don’t mind collapsing subplots, ditching characters, or even radically altering the point of view for 100,000 words of prose. I don’t mind because when Andrew tells me to do these things, I instantly see how much sense they make. For me, Andrew’s vision manages to expand the story’s possibilities while also clarifying what needs to be done to achieve those possibilities.

I should also say that the thought of revision is what gets me through the agony of drafting; revision is my happy zone, where things finally come together. I don’t mind cutting scenes or paragraphs or sentences that I love. I don’t mind writing new material. I don’t mind collapsing subplots, ditching characters, or even radically altering the point of view for 100,000 words of prose. I don’t mind because when Andrew tells me to do these things, I instantly see how much sense they make. For me, Andrew’s vision manages to expand the story’s possibilities while also clarifying what needs to be done to achieve those possibilities.

How, specifically, does the editing happen? I’ve often heard writer friends discuss the editorial letter, which I’m told is a fairly formal write-up of all the things that need to be done in revision for a manuscript to be acceptable to the editor. (More discussion of the editorial letter and an example here ) The editorial letter reflects the major first pass of editing and defines the focal areas for the main revision, after which (everyone hopes) it will be mostly scene- and sentence-level rewriting.

Unless I have suffered some serious memory loss—which is possible since I gave birth to my son during the early editorial process with What Can’t Wait—I don’t think I’ve ever gotten a formal editorial letter from Andrew. Instead, we tend to have several hour-longish phone calls where he tells me what his instincts are as far as what could or should change in the manuscript and why. Perhaps what is most important to me about how these things go is that the “why” is always intimately linked to the internal logic of the novel or its essential characteristics (as opposed, for example, to trends in the market or notions of what teens can “handle”). These conversations generally entail multiple epiphanies on my part and copious note-taking. The macro-level feedback from the phone calls comes along with scene-by-scene feedback via comments and edits in Word.

After responding to the major editorial feedback (over 2-5 months), I submit to Andrew my “final” manuscript. Once he reads and accepts it, I get the second half of the advance (the first half comes with signing the contract). There is still some back and forth and perhaps even some more substantive changes, but all the major pieces are in place. There will be at least one more full read-through with comments to address before the book goes to the next stage of copy-editing (line-by-line stuff and the standardization of things like “OK” for “okay” according to the publisher’s house style), which is done by wonderful people who work under Andrew.

What’s next? Then the book goes into production, and a while later (3-6 months) I get an email with galleys that give an idea of what the manuscript will look like as a “real” book. There will also be drafts of jacket copy, which I’m glad I don’t have to write, and cover designs. With What Can’t Wait, I wasn’t in on anything until after the final cover was chosen; with The Knife and the Butterfly, I saw about a dozen preliminary designs and got to weigh in on their relative merits. From contract to the printing of advance reader copies, the process has taken between a year and two.

What’s next? Then the book goes into production, and a while later (3-6 months) I get an email with galleys that give an idea of what the manuscript will look like as a “real” book. There will also be drafts of jacket copy, which I’m glad I don’t have to write, and cover designs. With What Can’t Wait, I wasn’t in on anything until after the final cover was chosen; with The Knife and the Butterfly, I saw about a dozen preliminary designs and got to weigh in on their relative merits. From contract to the printing of advance reader copies, the process has taken between a year and two.

Any words of advice for those on the road to publishing? The truth is that—at least for your first book—you will have little say in who your editor is. Your agent will submit the book where she or he thinks it’s a good fit, and if an editor bites and makes a reasonable offer, your agent will advise you to accept. There is no room in this process for mailing editors personality tests to check for compatibility.

What you can do is embrace the editorial process as an opportunity to discover more about your novel and your work as a writer. I find that the writer-editor dynamic—inevitably centered on the book—creates an amazing triangle of insight inside of which all kinds of possibilities for the story come into focus. I hope that’s the case for many other writers, too.

JOIN OUR 2014 READING CHALLENGE!

A year ago, The New York Times wrote about the lack of Latin@ literature in classrooms, which leaves the youngest members of the largest ethnic or racial minority in the U.S. with little chance to “see themselves in books.” The School Library Journal countered that the literature is there but needs to be promoted.

We believe both statements and would like to see more all around, meaning: more Latin@ children’s literature on bookshelves and in libraries and classrooms, more titles by and for Latin@s on year-end “Best of” lists and best-seller lists, more people buying, reading, and writing about Latin@ children’s literature.

We cannot control publishing and marketing, but we can read and write about Latin@s in children’s literature. So, as the new year approaches, we invite you to participate in our 2014 Reading Challenge. This would be a great way to diversify your reading lists and support already established and emerging writers who include Latin@s in their books. One of the best ways to express that diversity in kid lit is important is to buy, read, and write about these titles.

Here are the Guidelines:

- This challenge will run from January 1, 2014-December 31, 2014.

- Anyone can join! You don’t have to be a book blogger. WordPress doesn’t accept anything that uses JavaScript, so we can’t use a linky list. If you want to participate: post somewhere that you are joining the 2014 Latin@s in Kid Lit Reading Challenge, sign up in the comments, and include a direct link to your announcement. Copy and paste our reading challenge logo onto your site. If you don’t have a site, you can spread the word on Facebook, Twitter, or any other way.

- The goal is one book per month. You may post reviews on GoodReads (use a shelf dedicated to 2014 Latin@s in Kid Lit Reading Challenge), Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Facebook, or wherever else you post your reviews. Again, link back to the challenge. Each month, we will check up on participants, but you can also send a direct link to our email at: latinosinkidlit@gmail.com whenever you read and review a book. We will have a monthly round-up post that lists all reviews available online.

- Re-reads and crossovers from other challenges are fine.

- You may select books as you go.

- You can join at anytime during the year. Any books you have read in 2014 can be added.

- Prizes will be given to those who stick with it through the year!

- Any format, level (children’s, MG, or YA), or genre is welcome. The book, however, must be written by a Latin@ author and/or include Latin@ characters, settings, themes, etc.

“How will I find such books?” you ask.

“No problemo,” we say. Here are some suggestions:

- Browse our book lists and “Great Resources” tab for possibilities.

- Read School Library Journal’s Top 10 Latino-themed Books of 2013.

- Latinas 4 Latino Lit put out its own list of Remarkable Latino Children’s Literature of 2013 when the annual New York Times Notable Children’s Books list failed to honor a single book by or for Laint@s. They also offer book suggestions throughout the year.

- Search through the Pura Belpre Medal winners.

- Check out the winners of the International Latino Book Awards. The SLJ has a list of top prizes in various categories here.

Also, these titles were on “Best of” 2013 lists:

Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass by Meg Medina; SLJ, Kirkus

From Norvelt to Nowhere by Jack Gantos: PW

Enrique’s Journey by Sonia Nazario, Kirkus

Death, Dickinson, and the Demented Life of Frenchie Garcia by Jenny Torres Sanchez, Kirkus

Niño Wrestles the World written and illustrated by Yuyi Morales, Horn

The Summer Prince by Alaya Dawn Johnson, Kirkus

If you’re like us, then you will be reading anyway because you’re a person who loves books and children’s literature, in particular. Why not challenge yourself to add some Latin@ literature to your TBR pile? We hope you join us!

12 Days of Christmas Book Giveaway!!

¡Feliz Navidad! ¡Feliz Natal! Merry Christmas!

We are celebrating the holiday with a 12-book giveaway. Here’s how it works: enter by clicking on the “a Rafflecopter giveaway” link below the book images. From Christmas Day through Three Kings Day (January 6), one lucky winner will win one of these awesome books.

12 days = 12 books = 12 winners.

One of them could be you!

Remember, when you enter, you are putting your name into a pool for any of these books, not one in particular. To increase your chances, you can Tweet about the giveaway, follow us on Twitter, like our Facebook page, leave a comment, or share news of our giveaway on your blog or website. Good luck and thanks for entering and spreading the word about Latin@s in Kid Lit! Winners will be notified each day and arrangements will be made for shipping. We will ship only within the US and Canada.

After today, you will also find this information on a page in the menu area so that you can easily find it and enter over the next three weeks!

a Rafflecopter giveaway

Changes I’ve Seen, Changes I Hope to See

For our first set of posts, each of us will respond to the question: “Why Latin@ Kid Lit?” to address why we created a site dedicated to celebrating books by, for, or about Latin@s.

1963, Small Town, Alabama: I’m an immigrant kid in the second grade, well in command of English by now and eighty percent Americanized. Nobody brown or trigueño whose last name isn’t Quintero lives around here. Matter of fact, we’re one of the rare foreign families in the whole of Perry County—a bit of exotica, like strange but harmless birds that show up in the chicken yard one day.

With our nearest relatives in Argentina, seven thousand miles removed, my mother’s best friend is a war bride from Italy whose nostalgia for the old country goes hand in hand with Mama’s pining for Buenos Aires. Their conversations are peppered with overlapping terms from the Romance languages of their backgrounds. My father has his own ways of navigating the cultural void. He’s no communist, but he listens to Radio Habana Cuba on the shortwave radio. Fidel’s propaganda is something to ridicule, yet nothing else on the dial delivers Spanish. And he craves Spanish. That’s what your native tongue does—transports you back to the place you sprang from.

In 1963, nobody uses the terms Latino or Hispanic. Diversity may be in the dictionary, but if anyone’s applying it to ethnic groups, it hasn’t reached these backwaters of the American South. And as far as I know, the word multicultural hasn’t been invented; for that, we’ll have to wait another twenty years.

When I, the second-grade immigrant kid, drop by the Perry County Public Library, it’s to a creaky old clapboard house whose floors sag under the weight of books. The library at my elementary school is much the same, dusty and clogged with outdated materials. Luckily, my dad’s faculty status at a local college gives me library privileges. There, a small but gleaming collection of children’s books entices me up to the second floor.

I’m a bookworm. I devour everything published for kids. The books I love best entrance me through the power of story, not by how well their characters reflect me. Even so, I can’t help but notice that none of the characters has snapping brown eyes and olive skin. The girls in the books I read have names like Cathy and Susan. No one stumbles over these girls’ surnames and their parents don’t speak accented English. The closest thing to a Latino character I come across is Ferdinand, the Bull. ¡Olé!

Thirty-eight years later, when my youngest daughter is in fifth grade, we read aloud together almost daily. In Pam Muñoz Ryan’s Esperanza Rising, it’s wondrous to encounter a Latina character that feels like a real girl, not a shadow puppet with easy gestures that stand in for Hispanic. Fast forward to 2013, when Dora the Explorer is almost as well known as Mickey Mouse, and authors with names like Benjamin Alire Saenz and Guadalupe Garcia McCall show up in the stacks of the local public library with regularity. Compared to the Latin@ offerings of my childhood, this feels like an embarrassment of riches.

In March 2012, just after publishing my coming-of-age graphic novel, Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White, I find myself at the National Latino Children’s Literature Conference. There, my eyes are opened. I discover that the exploding population of young Latin@ American readers is still under served. On the whole, children’s publishing favors a model that reflects the Anglo world familiar to most editors, agents, and booksellers. The terms diversity and multiculturalism roll off the tongue easily now, but books about minority kids are still not rolling off the presses in sufficient numbers to match the need.

Through this blog, together with my younger collaborators— all of whom grew up in an era far more open to diverse cultures—I have the glorious opportunity to make a difference. I can celebrate the Latin@ characters that do exist in children’s books. I can help promote authors and illustrators who incline toward such stories or whose heritage broadcasts the message to Latin@ youth that they too can write and illustrate books. I can connect parents to new offerings in the biblioteca and hunt down librarians, scholars, and teachers eager to share their expertise with a non-academic audience. That’s what I’m here for—to dig out books, authors, and experts that affirm Latin@ identity and give them a friendly shove into the limelight.

Through Reading, Anything Is Possible

For our first set of posts, each of us will respond to the question: “Why Latin@ Kid Lit?” to address why we created a site dedicated to celebrating books by, for, or about Latin@s.

Our house was an oasis in the Chicago neighborhood crumbling around us. The house on the left was torn down after Old Man Louie died. The building on the right was bulldozed after some kids set it on fire. Inside our little haven, my parents encouraged me to read. Through books, I left that neighborhood to meet interesting characters in beautiful places who were struggling with life, love, and purpose, and who were trying to become free mentally, physically, or spiritually.

My parents moved us into better neighborhoods. Books moved me into a broader world of ideas and possibilities. A love for literature has made all the difference in my life. Now, I teach and write because I want children from all kinds of backgrounds to realize that, through literacy, anything is possible.

This may sound naïve, simplistic, or overly optimistic, but I honestly believe it.

I understand the challenges young people face because I’ve worked with middle and high school students for thirteen years. I’ve met the tattooed freshman girl whose education was interrupted because her mom had to move from place to place. At age fourteen, she had the reading level of a sixth grader. But guess what? She earned all As and Bs, joined a sport, and quickly became a leader in our school.

I’ve met the sixteen-year-old freshman boy who earned an in-school suspension for verbally and physically confronting a female teacher during the first week of school. He continued to struggle, earning Ds and Fs in his classes. But guess what? He read a book independently for the first time ever. He said he knew the teachers cared about him, and once he came to talk to me, tears streaming down his face after his girlfriend broke up with him via text message. He had made a collage with movie tickets and other mementos for their one-year anniversary that would never happen.

I’ve also met the jaded seventh-grade boy who asked me straight-out one day, “Why are you the only minority teacher in our school?”

All of these students are young Latin@s. They need safe places, trusted people to talk to, and answers to their questions. As a teacher who sees them for forty-five minutes a day, I do my best, and one of the most significant things I can do is encourage them to read. I can’t solve their problems at home or with their friends, but I can pass along my belief—given to me by my parents—that literacy is important and life-changing.

I want my students to develop the skills needed for academic and professional success. I also want them to enjoy a lifetime of beautiful places and interesting characters. I want them to have access to lots and lots of books with characters who look, speak, and act like them. Previous posts have outlined why it’s crucial for readers to “see themselves” in literature. But I also want them to see beyond their current selves. I want them to see realistic and fantastical futures. I want them to realize anything is possible.

Yes, you can be a U.S. Supreme Court Justice. Here, read a picture book about Sonia Sotomayor.

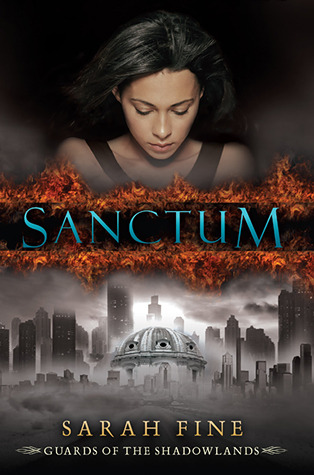

Yes, you can “escape” for a while and travel through the depths of the afterlife to save your best friend’s soul. Here, read Sanctum by Sarah Fine.

Yes, you can be a civil rights activist. Here, read biographies about César Chávez and Delores Huerta.

In the very distant future, if you discover you are a clone created to keep someone else alive, remember this: you will still have an identity and choices. For now, though, question whether science fiction will someday become nonfiction. Here, read The House of the Scorpion by Nancy Farmer.

Yes, you will survive your teen years. More than that, you will thrive. You’ll learn about love and family and friendship and acceptance and perseverance and integrity. Here, read Margarita Engle, Alex Sanchez, René Saldaña, Jr., Gary Soto, and Guadalupe Garcia McCall.

I’m involved with Latin@s In Kid Lit because I believe all children should have books in their hands, even when they’re too young to turn the pages, and they should all be told again and again, “Oh, the places you’ll go.”