A friendly reminder: we’re at the midway point of the Pitch Fiesta. Don’t wait much longer to submit your novel! Need a refresher on the rules and procedures? Go here.

Category Publishing

Forgive Me My Bluntness: I’m a Writer of Color and I’m Right Here In Front of You: I’m the One Sitting Alone at the Table

By René Saldaña, Jr.

I’ve avoided writing this piece long enough. Number one reason is that politically I’m a conservative, and the last thing I want to do is to appear as though I’m playing the race card. Which I’m not, though it might look like it. Doing so’s a cheap and underhanded thing to do. So I don’t. Second reason: what I’m tossing out there can be dangerous to my career as a writer, I’ve been told, because of who I’m aiming it at: the very folks who buy my books, or won’t due to my brazenness: librarians and fellow educators, my bread and butter. (I trust in the educator, though, enough to know that if we are about anything we are about growth through honest self-reflection; it’s my hope that this piece will serve as a catalyst for such). Third reason: during my own reflection over the last couple of years, mulling over whether I should or shouldn’t put this observation to paper, one of the cons was that maybe it’s just sour grapes I’m dishing. Ultimately, it’s not. Not even just a little.

My sincere desire is to talk from the heart, to share this heavy load I’ve been carrying, and to reciprocate. I’ll do my part to take on the equally heavy burden librarians and educators have been carrying for far too long. To, arm in arm, move in a direction upward when we’re talking about race, in particular race in children’s and YA publishing, a hot topic to be sure.

Let me tell you a story: I’m attending a librarians’ convention. I’ve been asked to sit on a panel or two, and at this point in my story I’ve met those obligations. Like happens at these functions, as a writer with a new book under my belt (best I can remember it’s A Good Long Way published by Piñata Books, an imprint of Arte Público Press), I’m also committed to sit for an hour at a table to sign copies of my latest. This is a very awkward thing for me to do. I really don’t like this part of my job. I mean, really, who am I? I’m not a top-tier author, and so I realize I won’t get the throngs of fans begging for my signature. (I found this out while sitting at another table, this one in D.C. at the National Book Festival in 2005, and I happened to be sitting next to Mary Pope Osborne, whose line was unimaginably long; I had to ask my wife, who was pushing our son in a stroller, and my sister-in-law to act as my line). Talk about eating humble pie. I get it. If a couple of teachers or librarians line up for my signature I count myself the most fortunate writer in the world. This time is no different from other times. I’m resolved to sit my time out, and if I get that librarian or two, I’ll make it a point to let them know how lucky I am to meet them.

Let me tell you a story: I’m attending a librarians’ convention. I’ve been asked to sit on a panel or two, and at this point in my story I’ve met those obligations. Like happens at these functions, as a writer with a new book under my belt (best I can remember it’s A Good Long Way published by Piñata Books, an imprint of Arte Público Press), I’m also committed to sit for an hour at a table to sign copies of my latest. This is a very awkward thing for me to do. I really don’t like this part of my job. I mean, really, who am I? I’m not a top-tier author, and so I realize I won’t get the throngs of fans begging for my signature. (I found this out while sitting at another table, this one in D.C. at the National Book Festival in 2005, and I happened to be sitting next to Mary Pope Osborne, whose line was unimaginably long; I had to ask my wife, who was pushing our son in a stroller, and my sister-in-law to act as my line). Talk about eating humble pie. I get it. If a couple of teachers or librarians line up for my signature I count myself the most fortunate writer in the world. This time is no different from other times. I’m resolved to sit my time out, and if I get that librarian or two, I’ll make it a point to let them know how lucky I am to meet them.

I truly feel that way. My love for libraries and librarians goes back a long, long way. Back to when I was checking out the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, and Little House on the Prairie during my elementary school years, and later books on UFOs, lost treasures, and the book that kept me in the reading act, Piri Thomas’s Stories from El Barrio during middle school, and throughout high school and college, to this day even, visiting our public library with my children. Along with my parents and a small handful of teachers, I owe librarians the bulk of my reading life. This is why, in the end, I feel I need to write this essay: I owe librarians dearly.

So, back to the story: I’m sitting there with Arte Público’s representative, and I do get the one or two curious librarians who ask about my work. I could tell them that I’ve published three other books with Random House, that I’ve published several short stories in several anthologies edited by Gallo, Springer, and Scieszka, but I don’t. The only book that matters to me is the one I just published. It’s my favorite book. Not my favorite because it is my most recent. It’s really and truly my favorite of all the titles I’ve published to date. I love A Good Long Way for so many reasons, but that’s the stuff for another essay. These librarians are kind and buy a copy for their collections, are already thinking of which students will benefit from this book most (and it’s not just Latino kids they’re telling me about).

From the time I sat, I’ve taken notice of the author two tables down from me. I actually just presented with her. Undeniably a rock star in the field. The kind of author for whom I’d stand in line to get her autograph. I know her personally, too. She’s a genuinely awesome person. I’ve used her work in my graduate adolescent lit classes. My students love her. I understand why these librarians are in line to get her signature and for a chance at a word or two, maybe a picture if time allows.

What I don’t get, though, is that not a one of these librarians in this other author’s line chances to look up in my direction, not that I can tell from my time at the table, anyhow. Not a one notices that just two tables down is another writer, one of color, a conversation that has been pushed to the fore recently? The Myers’ father and son team each wrote brilliant editorials for the New York Times (in the middle of me writing and rewriting this piece, wouldn’t you know it? The world of children’s and YA writing is shaken to the foundation at the news of Walter Dean Myers’ death and among his last acts was to force us to have this difficult conversation, so thanks to him). Others like Monica Olivera have added to that conversation in a blogpost on NBC Latino, The folks over at Lee & Low have ably challenged us to consider the state of children’s and YA publishing regarding race. Lee & Low on Twitter, especially, has rocked that boat. But it was a discussion we were having back then, too. Albeit mostly amongst ourselves, we writers and publishers and teachers and librarians of color. So it’s been brewing a long enough time.

So, what I’ve heard librarians say over the last decade and a half on my visits is that there are so many Latino children, and how unfortunate that there are so few Latino authors publishing books for them. “Just look at how excited these kids get,” they tell me, “to find one of their own publishing books.” It’s true, they do get excited to meet writers of color; I’ve seen it with my own eyes, heard it with my own ears. As a side note: I’ve also seen kids jump for joy at meeting white authors.

Can you tell I’m purposely going off on rabbit trails? I’m avoiding getting to the point again.

But whatever. There’s an urgency. We need to get beyond this hurdle. We need to courageously speak about race. Confront it head on. We’re told this also by U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder in one of his early speeches at the outset of his work for the Obama administration. We must face our shortcomings if we are to get to that place Dr. King dared us to dream about alongside him.

Anyway, these librarians have told me that there is so little of this material, and what there is of it is so hard to find.

Okay, I’m jumping in, confronting, being courageous, mostly trusting my readers to know I’m out for all our best interests, and especially for those we serve, our students: so,

NO! this material is not hard to find.

Simply look up and two tables down from where you’re standing, there I am. At that point in my career I’ve got some six books to my name. There. I. Am.

And if you think I’m an idiot, especially now that I’m telling you this, then do this other thing and you’ll know I’m right: walk up and down those aisles that usually are nowhere near the major publishers, the ones relegated to the edges of the main floor. They’re the small, independent presses. The outliers, in so many ways. You’ll know them because they’re the ones who don’t give out ARCs or free copies of books. Not because they don’t want to but because it’s not in their budgets to do so. Take 20 minutes per stall, look through their catalogues, their titles. For goodness’ sakes, talk to the reps, who are usually the publishers and editors themselves (when it’s not both of them, it’s either Bobby or Lee Byrd of Cinco Puntos Press manning their booth), and these reps will explain clearly what they have for you and your readers. They’re eager, as eager as you and I, to help all children reach their reading potential. Next, buy from them directly. Come ready with cash, checks, or cards. They’ll take any method of payment.

I’m not saying that the Bigs don’t publish authors of color. They obviously do. Random House has me and several other Latinos on their list. So has Dial. Scholastic. Little, Brown. S&S. Etc. They publish Black writers, and Asian writers. The difference is, though, that the smaller presses focus all their attention on writers of color, so they are experts at it. Arte Público Press/Piñata Books is one. Another is Cinco Puntos Press out of El Paso (of Sammy and Juliana in Hollywood fame but before that a picture book titled The Story of Colors by Subcomandante Marcos with magnificent illustrations by Domitila Domínguez, a book I’ve yet to find shelved in the libraries I’ve visited, even in deep South Texas where the majority of the population is Latino, Mexican American, and Mexican to be exact). Lee & Low, that sometime ago acquired Children’s Book Press and that recently started Shen Books, a new imprint that “focuses on introducing young readers to the cultures of Asia,” is yet another. The list of them, admittedly short—nevertheless, these few presses publish nothing but books by and about people of color. For all readers, but in particular readers of color.

The books are there.

All you have to do is to look for them.

And when you think you’ve found them all, look again. Because we’re still writing the books, publishers big and small are still publishing them. All we need is for you to look and look and look again until you can’t look no more, which likely means you’ve retired and you’re no longer pushing books into kids hands formally. But a librarian is a librarian is a librarian. You’ll be giving books to kids any chance you get ’til the day you die.

This is why I know I can write a piece like this, harsh as it might seem: because you’re educators first and foremost. And you’ll forgive me my bluntness. But we are not the focal point of this conversation, our children are. So we are either proactive and talk and then do, or we stand in the way of the progress necessary. Let’s be the former.

René Saldaña, Jr., is the author of the bilingual picture book Dale, dale, dale: Una fiesta de números/Hit It, Hit It, Hit It: A Fiesta of Numbers. He’s an associate professor of Language and Literature in the College of Education at Texas Tech University in West Texas. He’s also the author of several books for young readers, among them The Jumping Tree, Finding Our Way: Stories, The Whole Sky Full of Stars, A Good Long Way, and the bilingual Mickey Rangel detective series. He can be reached at rene.saldana@sbcglobal.net.

Writers: You’re Invited to Our First Ever Pitch Fiesta!

We’re baaaaaaack from vacation and so excited to announce the details for our first ever Pitch Fiesta, an online pitch event that could lead to writer-agent-publisher matches and future books by/for/about Latin@s. This event is open to middle grade and young adult writers. We’re sorry, but no picture book manuscripts this time around. We might have a separate event in the future for picture book writers and illustrators.

Before we get to the application information, let’s introduce our participating agents and publisher:

Adriana Dominguez, an agent at Full Circle Literary since 2009, has 15 years of experience in publishing, most recently as Executive Editor at HarperCollins Children’s Books, where she managed the children’s division of the Rayo imprint. She is a member of the Brooklyn Literary Council, which organizes the Brooklyn Book Festival, and one of the founders of the Comadres and Compadres Writers Conference in NYC. She is interested in middle grade novels and literary young adult novels. Adriana has a long trajectory of publishing underrepresented authors and illustrators, and welcomes submissions that offer diverse points of view.

Adriana Dominguez, an agent at Full Circle Literary since 2009, has 15 years of experience in publishing, most recently as Executive Editor at HarperCollins Children’s Books, where she managed the children’s division of the Rayo imprint. She is a member of the Brooklyn Literary Council, which organizes the Brooklyn Book Festival, and one of the founders of the Comadres and Compadres Writers Conference in NYC. She is interested in middle grade novels and literary young adult novels. Adriana has a long trajectory of publishing underrepresented authors and illustrators, and welcomes submissions that offer diverse points of view.

Adrienne Rosado is an agent at the Nancy Yost Literary Agency as well as the Foreign Rights Director. She is interested in literary and commercial fiction, especially YA, urban fantasy, multicultural fiction, women’s fiction, and new adult, all with strong voices and an authentic tone. She’s especially drawn to dark humor, innovative takes on classic literary themes, and Southern gothics. Adrienne is also on the lookout for quirky and smart narrative nonfiction, memoirs, pop science, and business books with a creative approach. Please no picture books, chapter books, poetry, or westerns.

Amy Boggs is an agent at the Donald Maass Literary Agency. She is looking for all things fantasy and science fiction, especially high fantasy, urban fantasy, steampunk (and its variations), YA, MG, and alternate history. She is also looking for unique works of contemporary YA, historical fiction, Westerns, and works that challenge their genre are also welcome. She seeks and supports projects and authors diverse in any and all respects, such as (but not limited to) gender, race, ethnicity, disability, and sexuality. Please no: thrillers, women’s fiction, picture books, chapter books, poetry, screenplays, or any debut work under 30,000 words in length.

Sara Megibow is an agent at the Nelson Literary Agency. Sara is looking for debut authors with a complete novel-length manuscript in any of these genres: middle grade, young adult, new adult, romance, erotica, science fiction or fantasy. Any sub-genre is accepted including paranormal, historical, contemporary, steampunk, fantasy, etc. In short – if you can write it, Sara will read it – as long as it’s 100% complete, novel-length, not previously published and in one of the above genres. Where does Diversity fit in? Sara is looking for manuscripts AND/OR authors representing diversity of religion, race, culture, socio-economic status, ability, age, gender and/or sexual orientation. Sara is on twitter @SaraMegibow and on Publishers Marketplace here: http://www.publishersmarketplace.com/members/SaraMegibow/

Sara Megibow is an agent at the Nelson Literary Agency. Sara is looking for debut authors with a complete novel-length manuscript in any of these genres: middle grade, young adult, new adult, romance, erotica, science fiction or fantasy. Any sub-genre is accepted including paranormal, historical, contemporary, steampunk, fantasy, etc. In short – if you can write it, Sara will read it – as long as it’s 100% complete, novel-length, not previously published and in one of the above genres. Where does Diversity fit in? Sara is looking for manuscripts AND/OR authors representing diversity of religion, race, culture, socio-economic status, ability, age, gender and/or sexual orientation. Sara is on twitter @SaraMegibow and on Publishers Marketplace here: http://www.publishersmarketplace.com/members/SaraMegibow/

Kathleen Ortiz is the director of subsidiary rights and a literary agent for New Leaf Literary & Media, Inc. She is an active member of AAR and SCBWI. She’s always on the hunt for outstanding stories with strong characters whose voice and journey stay with her long after she finishes reading the story. She loves YAs set within other cultures and experiences across all genres (though she’s a bit full up on sci-fi and dystopian at the moment).

Laura Dail of the Laura Dail Literary Agency received her Master’s degree in Spanish Literature from Middlebury College (but would prefer to consider works in English). She’s most interested in realistic YA, and funny middle grade and chapter books. She represents fiction and nonfiction, but no picture books, poetry, or screenplays. See more here: http://ldlainc.com/kids-teen-ya/

Arte Público Press, affiliated with the University of Houston, specializes in publishing contemporary novels, short stories, poetry, and drama based on U.S. Hispanic cultural issues and themes. Arte Público also is interested in reference works and non-fiction studies, especially of Hispanic civil rights, women’s issues and history. Manuscripts, queries, synopses, outlines, proposals, introductory chapters, etc. are accepted in either English or Spanish, although the majority of our publications are in English.

Arte Público Press, affiliated with the University of Houston, specializes in publishing contemporary novels, short stories, poetry, and drama based on U.S. Hispanic cultural issues and themes. Arte Público also is interested in reference works and non-fiction studies, especially of Hispanic civil rights, women’s issues and history. Manuscripts, queries, synopses, outlines, proposals, introductory chapters, etc. are accepted in either English or Spanish, although the majority of our publications are in English.

Piñata Books is Arte Público Press’ imprint for children’s and young adult literature. It seeks to authentically and realistically portray themes, characters, and customs unique to U.S. Hispanic culture. Submissions and manuscript formalities are the same as for Arte Público Press.

Now, here are the guidelines:

1. Writers who are Latin@ or writers of any ethnicity who have included Latin@ characters, settings, etc. in their manuscripts are eligible to apply.

2. You must have a complete manuscript at the time of the Pitch Fiesta. If an agent or editor is interested, you must have a complete manuscript ready to send. So, writers–get writing! Finish that manuscript!

3. Please read and consider what the agents are looking for. Please do not send us a query and first pages in a genre that does not mesh with their lists.

4. We will accept applications from September 2 through October 3. To apply, please send your query and the first 5-10 pages of your middle grade or young adult novel to our email: latinosinkidlit@gmail.com. In the subject line, please write: PITCH FIESTA ENTRY. Please post both the query and the first pages directly into the email. No attachments.

5. One of the Latin@s in Kid Lit members will read and respond to your email. During the month of October, we will help selected writers revise and polish queries and first pages to prepare for the Pitch Fiesta. Even though we will help you with your queries and first pages, please send us your best work. We have the right to reject any applications.

Queries and first pages will be posted on November 12 and 13. If an agent or an editor from Arte Público is interested, you will be contacted.

Exciting, right?

We hope writers will take advantage of this opportunity to present your work to publishing professionals who are actively seeking, and thereby supporting, diversity in kid lit!

Book Review: Otherbound by Corinne Duyvis

By Zoraida Córdova

By Zoraida Córdova

This month, we are taking a look at Latin@s in science fiction and fantasy. Today, we’re highlighting OTHERBOUND, a debut novel by Corinne Duyvis, which has received excellent reviews, including starred reviews from Kirkus, Publisher’s Weekly, School Library Journal, and The Bulletin of The Center for Children’s Books.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Amara is never alone. Not when she’s protecting the cursed princess she unwillingly serves. Not when they’re fleeing across dunes and islands and seas to stay alive. Not when she’s punished, ordered around, or neglected.

She can’t be alone, because a boy from another world experiences all that alongside her, looking through her eyes.

Nolan longs for a life uninterrupted. Every time he blinks, he’s yanked from his Arizona town into Amara’s mind, a world away, which makes even simple things like hobbies and homework impossible. He’s spent years as a powerless observer of Amara’s life. Amara has no idea . . . until he learns to control her, and they communicate for the first time. Amara is terrified. Then, she’s furious.

All Amara and Nolan want is to be free of each other. But Nolan’s breakthrough has dangerous consequences. Now, they’ll have to work together to survive–and discover the truth about their connection.

MY TWO CENTS: Otherbound by Corinne Duyvis is an ambitious novel that breaks the norm of YA fantasy.

Nolan is a seventeen-year-old boy with a prosthetic leg who has seizures, at least, what the grownups think are seizures. In actuality, he has a vivid connection with a girl named Amara who lives in the Dunelands—definitely not Arizona where Nolan and his family live.

The dual perspective—even the dual reality of it all–is interesting. I thought it might get distracting to have breaks where Amara’s world cuts into Nolan’s perspective in bold. But if Nolan can handle the after effects that come with what is pretty much a psychic invasion and still try to have a life, then I can handle it as a reader.

From the very beginning, we’re set up to understand the following things: Nolan leads a pretty average life. As average as it gets for a low income Latino family in Arizona. He has parents who work three jobs to pay for his meds. He has a younger sister who is 15 and has an attitude. Their Latin-ness isn’t brought up except for mentions of Grandmother Perez’s food and how Nolan’s parents go back and forth between speaking Spanish. The Spanish is always typed out in English, but since I speak Spanish I translated it in my head as I read along. And even though this is a fantasy novel, Duyvis makes a note of Nolan’s father writing angry letters to his school about banned books. It’s Arizona, you have to! So props.

After experiencing Nolan’s day-to-day, we’re then thrown into a completely different world with its own rules to understand. Amara is a servant. By nature of her birth she can’t read, write, or speak (literally, servants have their tongues cut off and are branded by palace). I love how the author didn’t shy away from the brutal life that this young girl has to endure. At the end of the day, Amara is a girl who is kidnapped and held against her will. She’s a slave, whose sole purpose in life is to protect a cursed princess through Amara’s ability to heal herself. Should princess Cilla’s blood spill, the curse will be unleashed. The Dunelands come with their own royalty system, magic, political intrigue, and adventure, which keeps the pace moving.

Nolan and Amara live in separate dimensions/planets but are both faced with disabilities that impede them from an autonomy that others take for granted. Amara’s ability to speak has been stolen from her. Never the less, she tries to over come this by learning how to read, despite the terrible punishment that awaits her if caught. While she does fear and question the people around her, she isn’t exactly a wallflower. She’s brave, loving, and loyal, traits that a physical disability can’t change.

As for Nolan, he lost a leg at a young age from a freak accident (brought on by the vision-seizures). While he can still be active, swim, go to school, and move around on his own, when you add painful “seizures” to that, the results are not good. It’s not a mental disability in the way that we treat depression or being bipolar, but it is in his head. On his part, he tries not to feel like a burden in his household. He’s constantly trying to give people the “right” kind of smile, and often lies about how he feels to get the grown-ups off his back about whether or not he’s “okay.” I think there’s a big pressure put on kids to “be okay” and it’s more for the adults than for the kids. Still, as he realizes the sacrifices his parents make for him, he takes to even the smallest chores–dishes, laundry, helping his sister rehearse for a play–to show that he can be present in his world, that he can be helpful.

Then the unexpected happens—through some circumstance of their connection (and the new meds), Nolan’s role goes from simply watching to doing. He can make Amara move. He can run through her, and it’s great to watch Nolan find the ability to move through Amara’s magical world. The levels of magic are complicated, and when Nolan and Amara discover each other, they become reliant on one another for survival. I mean, I’d be pissed off if some guy who was watching me for years and years, suddenly shows up and can control my body. Amara’s first reaction is to be mad, but Nola isn’t a creeper. He’s been part of her life for years and he truly cares about what happens to her. True, Amara would like to kiss the person she likes without Nolan snooping, but without Nolan, Amara’s ability to heal would not manifest. She needs him there for her to pass as a “healing mage.”

As he gets more and more involved in the political schemes of Amara’s world, Nolan is determined to make sure Amara survives, even if it means he feels pain. The way I read it is that he would much rather feel that physical pain than deal with the pressures of his reality. With everything that goes on in his real life–the meds, school, pressure, parents who constantly hover–Nolan gets a taste of being a hero without the Earthly limitations. As for Amara, her payoff is that Nolan gave her the ability to heal. There were so many times when she was tortured because her captor knew she would heal soon enough. Without Nolan, she would have probably died sooner. I can’t spoil the end, but Nolan’s connection came super in handy at the end. Even though their connection had to end sometime, it was great to see a relationship between a boy and a girl that wasn’t sexual, but bonded through adversity.

When I say that I’ve never read anything like this, I mean it. While I do feel like I know more about the characters than the actual fantasy world, I think I’m okay with that. There’s a young Mexican-American boy with a prosthetic leg who can see into another dimension and inhabit the body of an alien servant girl. This servant girl is bisexual and used as a ploy to a political regime way beyond her control. Definitely not your average YA.

AUTHOR: Corinne Duyvis is a lifelong Amsterdammer and former portrait artist now in the business of writing about superpowered teenagers. In her free time, she finds creative ways of hurting people via brutal martial arts, gets her geek on whenever possible, and sleeps an inordinate amount. Visit her at www.corinneduyvis.com or say HI on Twitter!

AUTHOR: Corinne Duyvis is a lifelong Amsterdammer and former portrait artist now in the business of writing about superpowered teenagers. In her free time, she finds creative ways of hurting people via brutal martial arts, gets her geek on whenever possible, and sleeps an inordinate amount. Visit her at www.corinneduyvis.com or say HI on Twitter!

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT Otherbound, visit your local library or bookstore. Also check out worldcat.org, indiebound.org, goodreads.com, amazon.com, and barnesandnoble.com.

Guest Post: Self-Publishing Often the Only Recourse for Writers of Color

“I am an immigrant.” When I visit schools, I always start my presentation with these words. Next, I ask the students to guess my country of origin. Their answers are often predictable and sometimes surprising: the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Mexico—Italy! When I tell them that I don’t speak Spanish but I do speak a little French, they call out a different list of countries until someone gets it right: Canada.

I open with my immigrant status in part because I once had a Latina approach me at the end of a presentation in Brooklyn and say, “I hate that word.” I didn’t ask about her status, but it was clear that she felt there was something shameful about being an immigrant. So I announce my own status with pride and use my presentation to demonstrate how my early years in Canada helped to shape the writer I became after I migrated to the US twenty years ago.

Immigration is a charged issue here, and though Canadians aren’t generally mentioned in the national debate, there’s still a pretty good chance I could run into trouble in Arizona. As a mixed-race woman of African descent, I often get read as Latina. Here, in New York City, I walk with my driver’s license, my passport, and my green card at all times because my Afro-Caribbean father taught me that some protections are reserved for citizens only (and only those citizens who aren’t brown like me). My father also urged me not to get involved in social justice movements, but I chose to disregard that advice.

I’m a black feminist—or what my father would call “a troublemaker.” I began to write for children over a decade ago because I couldn’t find culturally relevant material to use with my black students. I came to the US to attend graduate school, and there I developed a deeper understanding of intersectionality and invisibility. The title of one black feminist anthology encapsulates this perfectly: All the Women are White, All the Blacks are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave. Black women too often find themselves erased from discussions of racism and sexism, and when it comes to children’s literature, it can be just as easy for Afro-Latin@ kids to fall through the cracks.

Published by Skyscape, 2010

In 2000, I started a book club for the girls in my building. They were all black and we had been meeting for weeks before I realized that half the girls in the group were Panamanian. When they were with me, they spoke the black vernacular of their African American peers, but at home they spoke Spanish. When I wrote my YA time-travel novel A Wish After Midnight, I decided to give my protagonist a hybrid identity—Genna Colon’s mother is African American but her father is an Afro-Panamanian immigrant. When her father leaves the family to return to Panama, Genna yearns for a connection to her Latino heritage, but her jaded mother insists that race trumps ethnicity: “in America, it doesn’t matter where you’re from or what language you speak. Black is black and you might as well get used to it.”

Such a simplistic understanding of race is not uncommon, but many scholars, activists, and artists advocate for an appreciation of multiplicity—recognizing and respecting the specificity of blackness instead of reducing it to a single generic identity. As a black feminist writer, one of my goals is to counter the marginalization of black children in literature by writing stories about kids who are silenced and/or rendered invisible. I try to avoid the all too familiar “types” that seem to show up over and over again. Hakeem Diallo is a gifted basketball player but he’s also Muslim, biracial (black and South Asian), and he dreams of becoming a chef one day. Dmitri is a bird-watching math whiz who loses his mother to cancer and so lives with his elderly white foster mother. Judah is a Rastafarian teen from Jamaica who dreams of moving to Africa.

Self-published through CreateSpace under Rosetta Press

In 2009, I went to see the film adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s novella Coraline. I had some issues with the representation of women in the film, and went home thinking of a way to write a story about black boys and dolls. The end result was Max Loves Muñecas!—one of four chapter books that I self-published in May. The story follows three homeless boys in 1950s Honduras who are taken in by a kind woman who makes dolls. I was inspired by my father’s childhood in the Caribbean. He was raised by his grandmother on the island of Nevis, and with no money to spare, my father learned to make his own toys out of recycled materials. They were poor but my great-grandmother made sure my father was always presentable and well behaved. Respectability meant a lot since the family had so little.

I knew I wanted my story to take place within the Caribbean basin, but I had limited knowledge of Latin America. I chose Honduras for the setting of Max Loves Muñecas! because the best doll maker I know is Afro-Honduran designer Cozbi Cabrera. Also my community college student Saira, a Garífuna woman, gave a presentation in class about the murder rate in Honduras—the highest in the world. This is due, in part, to street violence fueled by gang members who have been deported from the US. My story isn’t set in contemporary Honduras, but the book does challenge gender norms and exposes the tender, creative side so many boys are forced to conceal.

I often write about boys because I have seen firsthand how expressive, sensitive boys shut down as they mature and assume the hard, unfeeling posture of a young “thug.” Boys around the world are socialized in a way that leaves them unable to reveal their authentic selves and the consequences can be devastating—especially for girls, but for boys and men as well. As a feminist I realize that if I want to end violence against women and girls, I have to start paying more attention to boys.

These issues mean a lot to me, but social justice is not generally a priority for the children’s publishing industry. For the past five years I have written essays and given talks about the glaring inequality within publishing, and the issue has garnered more attention recently thanks to the social media campaign #WeNeedDiverseBooks. Several editors rejected Max Loves Muñecas! (the last one wrote, “Zetta is such a lovely writer and I did enjoy this story – but I just don’t think we can find a big enough market for it”) and so the story sat on my hard drive for five years until I finally decided to self-publish it. I found a Honduran illustrator, Mauricio J. Flores, on Elance; he completed ten black and white illustrations and I used the print-on-demand site CreateSpace to publish the book.

The biggest challenge with self-publishing is finding a way to connect your books with readers. The Brown Bookshelf recently ran a series called “Making Our Own Market,” and I contributed a guest post in which I shared my core objectives:

- To generate culturally relevant stories that center children who have been marginalized, misrepresented, and/or rendered invisible in children’s literature.

- To produce affordable, high-quality books so that families—regardless of income—can build home libraries that will enhance their children’s academic success.

- To produce a steady supply of compelling, diverse stories that will nourish the imagination and excite even reluctant readers.

If these objectives resonate with you, I hope you’ll give my books a chance. The bias against self-published books is hard to overcome; major outlets refuse to review them, and only a few book bloggers are willing to give self-published books a chance (thank you, Latin@s in Kid Lit). Many are poorly written and shoddily produced, but when publishing gatekeepers exclude so many talented writers of color, self-publishing is often our only recourse. If we wait for the industry to change, another generation of children will grow up as I did—without the “books-as-mirrors” they need and deserve.

Born in Canada, Zetta Elliott earned her PhD in American Studies at NYU. Her poetry has been published in several anthologies, and her plays have been staged in New York and Chicago. Her essays have appeared in Horn Book Magazine, School Library Journal, and The Huffington Post. Her picture book, Bird, won the Honor Award in Lee & Low Books’ New Voices Contest and the Paterson Prize for Books for Young Readers. Elliott’s young adult novel, A Wish After Midnight, has been called “a revelation…vivid, violent and impressive history.” Ship of Souls, published in February 2012, was included in Booklist’s Top Ten Sci-fi/Fantasy Titles for Youth and was a finalist for the Phillis Wheatley Book Award. Her third novel, The Deep, was published in November 2013. She currently lives in Brooklyn.

Born in Canada, Zetta Elliott earned her PhD in American Studies at NYU. Her poetry has been published in several anthologies, and her plays have been staged in New York and Chicago. Her essays have appeared in Horn Book Magazine, School Library Journal, and The Huffington Post. Her picture book, Bird, won the Honor Award in Lee & Low Books’ New Voices Contest and the Paterson Prize for Books for Young Readers. Elliott’s young adult novel, A Wish After Midnight, has been called “a revelation…vivid, violent and impressive history.” Ship of Souls, published in February 2012, was included in Booklist’s Top Ten Sci-fi/Fantasy Titles for Youth and was a finalist for the Phillis Wheatley Book Award. Her third novel, The Deep, was published in November 2013. She currently lives in Brooklyn.

Other books by Zetta Elliot. For a full list, visit her blog.

Published by Lee and Low, 2008

Published by Skyscape, 2012

One of four kids books self-published, 2014

Seven Things You Need to Know About After the Book Deal

Have you ever noticed that, in romantic comedies, the end is very often a wedding? What’s up with that? Love stories don’t end at a wedding. That’s when real life begins, the business of figuring out who does the laundry, where you’re going to live, and how in the world you figure out where you spend Thanksgiving and Christmas. It’s the same thing with publishing. The day you ink the book deal may be the happy ending in the movie version, but in real life it’s just the start of the story.

Have you ever noticed that, in romantic comedies, the end is very often a wedding? What’s up with that? Love stories don’t end at a wedding. That’s when real life begins, the business of figuring out who does the laundry, where you’re going to live, and how in the world you figure out where you spend Thanksgiving and Christmas. It’s the same thing with publishing. The day you ink the book deal may be the happy ending in the movie version, but in real life it’s just the start of the story.

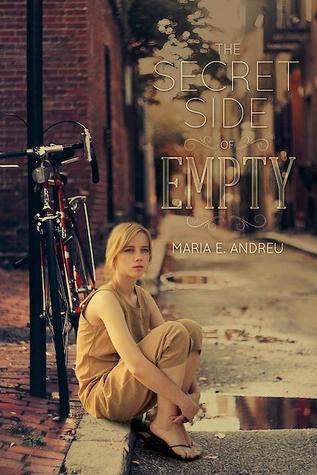

After many years of dreaming of being a writer, I got my movie-worthy happy ending. I got the first agent I pitched for The Secret Side of Empty, from a house so prestigious just reading their client list gives me goose bumps. We sold the book in the first round of submissions to a publisher who has done amazing things for the book, truly an ideal publisher for my first time at the rodeo. (And there was more than one offer to weigh). Anyone who hears my publishing story wants to stop me there and sort of bask in the moment, happy in the knowledge that it does happen that way sometimes. And it does.

But then you wake up the next day.

Just like no one tells you what to do once you get back from the honeymoon, here are 7 things no one will tell you about what it’s like AFTER the book deal.

- Editing is terrifying. Sure, you’ve edited before. You’ve joined critique groups. Maybe you’ve been brave and gone to pitch slams and other places where your words have been torn apart and criticized. Great. Now you’ll have a team of bona-fide professionals poring over your every word. I got an editorial letter so detailed that I shut the document immediately after seeing its page count (let’s just say this: it was in the double digits) and couldn’t make myself open it for 2 weeks. Be prepared. It’s not about you. It’s about making the work the best it can be.

- Book promotion is exhausting. Yes, you’ve waited your whole life for it. Yes, you’re going to love most of it. And you’re going to be exhausted anyway. You’ll be thrilled to learn that your publisher will schedule a blog tour for you (maybe, if you’re lucky). You’ll forget that it means you’ll have to actually write all those posts, answer all those interview questions, send head shots, book covers and photos of your frizzy hair in the 8th grade or the bicycle you learned to ride on. Then you’ll go to schools, libraries, festivals, and grocery stores and auto body shops too, if they’ll take you. Fun, yes. Mostly. Take naps now.

- Your launch date is not real. Just like a lot of brides stress the wedding and forget it’s actually a marriage they should be planning, so too a lot of authors obsessively plan the Twitter party and Tumblr extravaganza that will be their Launch Day, forgetting that it isn’t really even a Real Thing. My books shipped almost 3 weeks early. When I asked, a helpful professional told me, “Unless your name is J.K. Rowling, no one’s taking up warehouse space to perfectly orchestrate your big reveal.” It will help you to remember that book promotion, like a marriage, is something that you’re in for the long haul. So don’t stress the day so much and come up with a long-term strategy.

- It’s a crowded marketplace. You thought it was hard to get attention when you were in the throng of hopefuls? Wait until you see your book on a shelf full of all the others who broke out of the pack. You’ve got a couple of seconds to catch a potential reader’s attention, online and off. If the competition of trying to get published bothers you, you should know it doesn’t stop after your book is out in the world.

- Reviews hurt. Bad reviews can cut you to the quick. Even good ones can sometimes leave you scratching your head. Much ink has been spilled advising writers not to let critics get to them. That’s great advice. Also pretty hard to follow, particularly at first when you’re hungry for any sign of how your book is doing and what people think. My advice is to ignore reviews completely – good and bad. It is advice you will not follow. Hold on, I’ve got to go check my Goodreads page real quick.

- People will find things in your book you didn’t realize were there. I’ve had readers ask me about love triangles I didn’t intend to include and legislation I didn’t mean to reference. I’ve had readers write to tell me they love a character and a whole bunch of others reach out to tell me how much they loathe that very same character. All with supporting evidence. When you release your book out into the world, it is no longer yours alone.

- It will be hard to find time to write. Do you struggle with finding time now? Imagine having all the responsibilities you have now, except take away a lot of your free time on weekends and evenings (because you’re at book festivals and you’re writing blog posts). Now write. That’s what it’s like to try to write books # 2, 3 and beyond.

Lest I seem like too much of a downer, let me say that publishing my debut novel has been magical, the culmination of a lifelong dream. I’ve been honored to speak at schools and libraries and events all over the country and have received wonderful attention from the trade reviewers. I’ve gotten the tingles when I discovered that my book is in libraries as far away as Singapore, Australia, and Egypt, as well as across the United States. Just imagine… my words being read by someone right now somewhere halfway around the globe. Amazing! I share my “things no one will tell you” not to discourage you, but to invite you to look at the whole picture. Like anything worth striving for – a marriage, parenthood, career – publishing a book is a massive undertaking with highs and lows. Once you reach the peak of Published Author, there is another one, just as big, right in front of you. Then another, and another, all the way to the horizon. And that’s what makes it beautiful.

Maria E. Andreu is the author of the novel The Secret Side of Empty, the story of a teen girl who is American in every way but one: on paper. She was brought to the U.S. as a baby and is now undocumented in the eyes of the law. The author draws on her own experiences as an undocumented teen to give a glimpse into the fear, frustration and, ultimately, the strength that comes from being “illegal” in your own home.

Maria E. Andreu is the author of the novel The Secret Side of Empty, the story of a teen girl who is American in every way but one: on paper. She was brought to the U.S. as a baby and is now undocumented in the eyes of the law. The author draws on her own experiences as an undocumented teen to give a glimpse into the fear, frustration and, ultimately, the strength that comes from being “illegal” in your own home.

Now a citizen thanks to legislation in the 1980s, Maria resides in a New York City suburb with all her “two’s”: her two children, two dogs and two cats. She speaks on the subject of immigration and its effect on individuals, especially children. When not writing or speaking, you can find her babying her iris garden and reading post apocalyptic fiction. You can also find her on Facebook and Twitter.

The Secret Side of Empty has received positive reviews from Kirkus and Publisher’s Weekly, among others. The novel was also the National Indie Book Award Winner and a Junior Library Guild Selection.