by Cecilia Cackley

by Cecilia Cackley

Juana Medina’s latest book is Juana and Lucas, published this September by Candlewick Books. An illustrated early chapter book, it is narrated by Juana, a little girl living with her dog Lucas in Bogotá, Colombia, who gives the reader a tour of her city and her life. Juana loves her family, her friends and her school, but she does not like having to learn English. Only when her family reminds her that they have a trip planned to the theme park Astroland in the United States, does Juana admit that maybe English has its uses after all.

Medina was born in Colombia and now lives in Washington, DC, where she works out of a shared studio space on the northwest side of the city. I spent an afternoon with her there, looking at the tools she used to create the illustrations for Juana and Lucas and talking about the process of creating the book.

Medina started out working in graphic design. She originally came to the United States from Colombia to study at the Corcoran School in DC, but found that the program there didn’t fit her needs and instead she moved to the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Her study of graphic design prepared Medina to write and illustrate this story. “It gave me great structure to understand books,” she says, adding that studying alongside undergrad students “made it more fun, gave it a sense of exploration.”

That sense of exploration is on full display in Juana and Lucas, which features a loose, sketchy quality to the ink drawings. Medina points to the British illustrator Quentin Blake as a key influence, noting that he draws with both hands, and she often does too, or sometimes draws with one hand and colors with the other. Another favorite artist is Joaquin Salvador Lavado, better known by his pen name Quino, who created the iconic comic strip Mafalda for the Argentine newspaper El Mundo. Medina gushes about Quino’s “level of expressiveness.” She points out: “He includes wit in such simple traces and achieves complexity and an incredible level of detail in just a few lines.”

That sense of exploration is on full display in Juana and Lucas, which features a loose, sketchy quality to the ink drawings. Medina points to the British illustrator Quentin Blake as a key influence, noting that he draws with both hands, and she often does too, or sometimes draws with one hand and colors with the other. Another favorite artist is Joaquin Salvador Lavado, better known by his pen name Quino, who created the iconic comic strip Mafalda for the Argentine newspaper El Mundo. Medina gushes about Quino’s “level of expressiveness.” She points out: “He includes wit in such simple traces and achieves complexity and an incredible level of detail in just a few lines.”

Medina likes the ability to switch between different artistic media from book to book. For her, it’s about what the story asks for. Juana and Lucas is illustrated in pen and ink, and colored with watercolor, which is a very personal medium for Medina, as it reminds her of childhood and illustrations by favorites such as Quentin Blake. The personal components of the story of Juana and Lucas meant that watercolor felt right for the book, because it gives it a sense of nostalgia. Other illustration projects that Medina has worked on, such as Smick, written by Doreen Cronin, and the counting book 1 Big Salad combine found objects with digital drawings.

For Juana and Lucas, Medina experimented with sketches in pencil first, then used a light box to draw the final version of each illustration in ink. Watercolor came next and the drawing was then scanned so that the colors could be adjusted digitally. This process also allowed Medina to correct small errors without having to redraw an entire composition. She showed me one spread containing an airplane that hadn’t been in the original sketch. Later in the process, it was added digitally to cover up an unruly inkblot!

For Juana and Lucas, Medina experimented with sketches in pencil first, then used a light box to draw the final version of each illustration in ink. Watercolor came next and the drawing was then scanned so that the colors could be adjusted digitally. This process also allowed Medina to correct small errors without having to redraw an entire composition. She showed me one spread containing an airplane that hadn’t been in the original sketch. Later in the process, it was added digitally to cover up an unruly inkblot!

For Juana and Lucas, her first chapter book, Medina wrote the story first, and then went back to draw. Through writing and rewriting, she found the balance between word and image. She says “It’s important to make a book where even if a kid can’t read yet, they can still get a sense of the story.” The relationship between Juana and Lucas, in particular, is mostly visual, so even if Juana isn’t talking about him very much in the text, you see them interacting in the illustrations. Medina points out that this is more realistic, as our interactions with our pets are mostly visual and tactile. Having narrative both in the text and in the illustrations makes this a great choice for readers still transitioning from picture books to chapter books.

The dynamic presentation of text (words that curve, get bigger or in other ways deviate from the standard type) featured throughout the story was Medina’s idea. Her thinking is that typography is part of language, explored, and it can cue certain meanings of words that may be unfamiliar to young readers.

The dynamic presentation of text (words that curve, get bigger or in other ways deviate from the standard type) featured throughout the story was Medina’s idea. Her thinking is that typography is part of language, explored, and it can cue certain meanings of words that may be unfamiliar to young readers.

Medina says about her writing process: “I was telling a story that was personal in my second language, so that was hard. I was lucky to be working with an editor who got it—figuring out the exact language to make it understandable without imposing too much. Candlewick has been great at not treating the text as precious, but instead seeing what is working and what isn’t.”

The book was written first in English, and she says it was almost like writing lyrics, choosing places where Spanish could be inserted in a way that made sense. Medina wanted to avoid echoing the English words in Spanish. She felt it was important to be respectful of readers and give them a chance to figure out the meanings of the Spanish words on their own. Its inclusion adds richness and reminds the reader that English isn’t Juana’s first language. The mix of the two languages feels very genuine, because mixing languages happens with all multilingual children. Their brains are trying to figure it out, and it’s natural for them to begin a sentence in one language and end it in another. The Spanish hasn’t deterred young readers who aren’t already familiar with the language. According to Medina, “I gave it to my niece, who was the first kid to ever read it. She doesn’t speak Spanish, but as soon as she finished the book, she went to the computer and pulled up Google Translate. After a moment she turned to me and said, ‘Me encantó tu libro,’ which was just…I was crying.”

For readers in the United States used to seeing European cities such as London or Paris in children’s literature, it’s a breath of fresh air to get such a detailed, child’s-eye view of a major South American city. Medina went back to Bogotá after writing several versions, and says the trip was bittersweet. “It was the first time there without my grandparents, without having a place there to call home. It was a difficult trip, but it was sweet to see the mountains and smell the eucalyptus, and it was validating to see everything. I took some license in the book. I’m not tying myself to fact-checking everything, which was liberating in a way. There was a lot I left out, especially surrounding the conflict and civil war I grew up with. That’s something I’ll maybe address in another book. The hardest illustration was my grandparents’ house, which no longer exists. It was a safe haven, so no illustration could truly do it justice.”

For readers in the United States used to seeing European cities such as London or Paris in children’s literature, it’s a breath of fresh air to get such a detailed, child’s-eye view of a major South American city. Medina went back to Bogotá after writing several versions, and says the trip was bittersweet. “It was the first time there without my grandparents, without having a place there to call home. It was a difficult trip, but it was sweet to see the mountains and smell the eucalyptus, and it was validating to see everything. I took some license in the book. I’m not tying myself to fact-checking everything, which was liberating in a way. There was a lot I left out, especially surrounding the conflict and civil war I grew up with. That’s something I’ll maybe address in another book. The hardest illustration was my grandparents’ house, which no longer exists. It was a safe haven, so no illustration could truly do it justice.”

Readers will be happy to learn that Medina is already working on a second book in the Juana and Lucas series. In addition, her follow up to 1 Big Salad, an ABC book called ABC Pasta, will be out in the spring from Penguin Random House. Medina’s advice to other Latinx artists looking to break into illustration is to be persistent and disciplined about their work. “Tell your own stories,” she says “Not the ones that will simply please an audience, but the ones that are meaningful.” And like her character Juana, struggling to balance her two languages, Medina advises artists to “find the language for the story you want to tell.”

Juana Medina is a native of Colombia, who studied and taught at the Rhode Island School of Design. Her illustration and animation work have appeared in U.S. and international media. Currently, she lives in Washington, DC, and teaches at George Washington University. See more of Juana’s work at her official website.

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at www.witsendpuppets.com.

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at www.witsendpuppets.com.

Aren’t children too young to think about social and political issues? Should we interfere with children’s innocence by prematurely exposing them to the darker sides of life?

Aren’t children too young to think about social and political issues? Should we interfere with children’s innocence by prematurely exposing them to the darker sides of life?  Joelito’s Big Decision/ La gran decisión de Joelito

Joelito’s Big Decision/ La gran decisión de Joelito Our book tells the tale of Joelito, who eats dinner at MacMann’s Burger Restaurant with his family every Friday. The story begins one Friday when he finds his best friend Brandon and Brandon’s parents at the restaurant entrance, holding up signs saying, “Low Pay is Not OK,” and “Fight for 15,” and urging the hungry Joelito not to eat at MacMann’s tonight.

Our book tells the tale of Joelito, who eats dinner at MacMann’s Burger Restaurant with his family every Friday. The story begins one Friday when he finds his best friend Brandon and Brandon’s parents at the restaurant entrance, holding up signs saying, “Low Pay is Not OK,” and “Fight for 15,” and urging the hungry Joelito not to eat at MacMann’s tonight. Hope

Hope Author Ann Berlak has been a teacher and teacher educator for over fifty years. She envisions schools as places where children learn to become active, caring participants in the creation of a world that works for everyone. Joelito’s Big Decision/La gran decisión de Joelito was selected for the 2016-2017

Author Ann Berlak has been a teacher and teacher educator for over fifty years. She envisions schools as places where children learn to become active, caring participants in the creation of a world that works for everyone. Joelito’s Big Decision/La gran decisión de Joelito was selected for the 2016-2017

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Meet Maya, Isabel’s flower girl, as she describes in vivid detail the exciting wedding day. Maya introduces us to Danny, the ring bearer; Aunt Marta, crying big tears; Uncle Trino, jump-starting a car in his tuxedo; and Rafael, the groom, with a cast on his arm. Of course, the big day also includes games, dancing, cake, and a mariachi band that plays long into an evening no one will ever forget.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Meet Maya, Isabel’s flower girl, as she describes in vivid detail the exciting wedding day. Maya introduces us to Danny, the ring bearer; Aunt Marta, crying big tears; Uncle Trino, jump-starting a car in his tuxedo; and Rafael, the groom, with a cast on his arm. Of course, the big day also includes games, dancing, cake, and a mariachi band that plays long into an evening no one will ever forget. ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Stephanie Garcia is an illustrator, graphic designer, art director, and design consultant, with a wealth of experience in the corporate world and the classroom, where she shares her knowledge with others. Learn more about her in

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Stephanie Garcia is an illustrator, graphic designer, art director, and design consultant, with a wealth of experience in the corporate world and the classroom, where she shares her knowledge with others. Learn more about her in  ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Gary Soto is the author of multiple picture books, including the Chato series, which won the Pura Belpré illustrator award for Susan Guevara. He also published many novels for youth, as well as books of short stories for young readers, and collections of essays and poems. His awards include the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, the Andrew Carnegie Medal, and the National Book Award. Learn more at

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Gary Soto is the author of multiple picture books, including the Chato series, which won the Pura Belpré illustrator award for Susan Guevara. He also published many novels for youth, as well as books of short stories for young readers, and collections of essays and poems. His awards include the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, the Andrew Carnegie Medal, and the National Book Award. Learn more at  Lila Quintero Weaver

Lila Quintero Weaver Ana writes: “This cover design was created in watercolor, inks and gouache. I’m so happy to share with everyone the face of an unknown, mysterious and mischievous creature: the chupacabra!”

Ana writes: “This cover design was created in watercolor, inks and gouache. I’m so happy to share with everyone the face of an unknown, mysterious and mischievous creature: the chupacabra!”

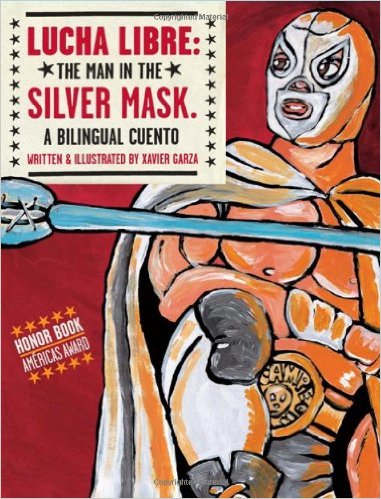

By Xavier Garza

By Xavier Garza But there was another reason I wrote books about luchadores, dating back to when I was a seven-year-old child going to the movies with my dad. It was the summer of 1974 when my father took me to the H&H Drive-In in my hometown of Rio Grande City, Texas. The marquee heralded a double-feature matinee that consisted of a Japanese monster movie and an action-thriller flick from the world of Mexican cinema. The second film was titled Santo contra las momias de Guanajuato (The Saint versus the Mummies of Guanajuato). I was all too familiar with radioactive fire-breathing Japanese Kaijua monster movies of the Godzilla variety, but up until that night, I had not yet been introduced to the masked heroes and villains of lucha libre.

But there was another reason I wrote books about luchadores, dating back to when I was a seven-year-old child going to the movies with my dad. It was the summer of 1974 when my father took me to the H&H Drive-In in my hometown of Rio Grande City, Texas. The marquee heralded a double-feature matinee that consisted of a Japanese monster movie and an action-thriller flick from the world of Mexican cinema. The second film was titled Santo contra las momias de Guanajuato (The Saint versus the Mummies of Guanajuato). I was all too familiar with radioactive fire-breathing Japanese Kaijua monster movies of the Godzilla variety, but up until that night, I had not yet been introduced to the masked heroes and villains of lucha libre.

Público Press

Público Press

Xavier Garza is an author, teacher, artist, and storyteller whose work is a lively documentation of life, dreams, superstitions, and heroes in the bigger-than-life world of South Texas. Xavier has exhibited his art and performed his stories in venues throughout Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. He is the author of several books for children and young adults. His Maxmilian and the Mystery of the Guardian Angel: A Bilingual Lucha Libre Thriller received a 2012 Pura Belpré Honor designation. Follow Xavier’s adventures on Twitter (his handle is @CharroClaus) and

Xavier Garza is an author, teacher, artist, and storyteller whose work is a lively documentation of life, dreams, superstitions, and heroes in the bigger-than-life world of South Texas. Xavier has exhibited his art and performed his stories in venues throughout Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. He is the author of several books for children and young adults. His Maxmilian and the Mystery of the Guardian Angel: A Bilingual Lucha Libre Thriller received a 2012 Pura Belpré Honor designation. Follow Xavier’s adventures on Twitter (his handle is @CharroClaus) and

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR (from her

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR (from her  Marianne Snow Campbell

Marianne Snow Campbell