Review by Lettycia Terrones, MLIS, PhD Student

Malú and the D.I.Y. (with a little help from the Elders) Aesthetic of Punk Rock Girls

There is a scene half-way through Celia C. Pérez’s brilliant middle-grade novel The First Rule of Punk that pulls so powerfully at the heartstrings of all those who have ever struggled with forming their identity as a minoritized person in the U.S. Having just wrapped up the first practice session of her newly formed punk band, The Co-Co’s, Malú (María Luisa O’Neill-Morales), the novel’s protagonist, learns an important lesson about what it means to be “Mexican.” It’s a lesson that not only connects Malú to her cultural heritage in a way that is authentic, it also invites her to self-fashion an identity that encompasses all parts of her, especially her punk rock parts! The lesson comes at the hands of Mrs. Hidalgo, the mother of Joe (José Hidalgo) who is Malú’s friend-in-punk, fellow seventh-grader at José Guadalupe Posada Middle School, and the guitarist of her band. And, it’s a lesson that complements those imparted by the many teachers guiding Malú to incorporate the complexity of seemingly disparate parts that make up who she is.

There is a scene half-way through Celia C. Pérez’s brilliant middle-grade novel The First Rule of Punk that pulls so powerfully at the heartstrings of all those who have ever struggled with forming their identity as a minoritized person in the U.S. Having just wrapped up the first practice session of her newly formed punk band, The Co-Co’s, Malú (María Luisa O’Neill-Morales), the novel’s protagonist, learns an important lesson about what it means to be “Mexican.” It’s a lesson that not only connects Malú to her cultural heritage in a way that is authentic, it also invites her to self-fashion an identity that encompasses all parts of her, especially her punk rock parts! The lesson comes at the hands of Mrs. Hidalgo, the mother of Joe (José Hidalgo) who is Malú’s friend-in-punk, fellow seventh-grader at José Guadalupe Posada Middle School, and the guitarist of her band. And, it’s a lesson that complements those imparted by the many teachers guiding Malú to incorporate the complexity of seemingly disparate parts that make up who she is.

Before leaving the Hidalgo basement, which serves as the band’s practice space, Mrs. Hidalgo asks Malú to pull out a vinyl copy of Attitudes by The Brat. Putting needle to the :format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-2797380-1301471350.jpeg.jpg) record, Malú listens to the first bars of “Swift Moves” the EP’s opening song and asks in wonder, “Who is she?” To which Mrs. Hidalgo replies, “That’s Teresa Covarrubias.” And, so begins a history lesson for the ages. By introducing Malú to Teresa Covarrubias, the legendary singer of The Brat—the best punk band ever to harken from East L.A. —Mrs. Hidaldo, in a true punk rock move, being that she’s one herself, reclaims the cultural lineages that are so often erased and suppressed by dominant narratives, by affirming to Malú: “And they’re Chicanos, Mexican Americans … Like us.” (Pérez 162). Mrs. Hidalgo opens a door and illuminates for Malú something so beautiful and lucent about our culture. She designates this beauty as being uniquely part of a Chicanx experience and sensibility. So that in this moment, Malú’s prior knowledge and understanding of the punk narrative expands to include her in it as a Mexican American girl. She too belongs to this lineage of Mexicanas and Chicanas that made their own rules, which as Malú will go on to learn, indeed is the first rule of punk (Pérez 310).

record, Malú listens to the first bars of “Swift Moves” the EP’s opening song and asks in wonder, “Who is she?” To which Mrs. Hidalgo replies, “That’s Teresa Covarrubias.” And, so begins a history lesson for the ages. By introducing Malú to Teresa Covarrubias, the legendary singer of The Brat—the best punk band ever to harken from East L.A. —Mrs. Hidaldo, in a true punk rock move, being that she’s one herself, reclaims the cultural lineages that are so often erased and suppressed by dominant narratives, by affirming to Malú: “And they’re Chicanos, Mexican Americans … Like us.” (Pérez 162). Mrs. Hidalgo opens a door and illuminates for Malú something so beautiful and lucent about our culture. She designates this beauty as being uniquely part of a Chicanx experience and sensibility. So that in this moment, Malú’s prior knowledge and understanding of the punk narrative expands to include her in it as a Mexican American girl. She too belongs to this lineage of Mexicanas and Chicanas that made their own rules, which as Malú will go on to learn, indeed is the first rule of punk (Pérez 310).

Joan Elliott-Said a.k.a. Poly-Styrene

This “like us,” this cultural resonance, this CORAZONADA to our heritage as Chicanx people in the U.S. is exactly the attitude and voice that can only come from one who has experienced what it’s like to live in the liminal spaces where as you’re neither from here nor from there. Pérez, herself of bicultural Cuban and Mexican heritage, indeed speaks to this experiential knowledge, saying in a recent interview in The Chicago Tribune that it wasn’t until college when she read Pocho by José Antonio Villareal that she recognized her own experience reflected in the pages of literature for youth (Stevens). Pérez in The First Rule of Punk speaks to the same imperatives that Marianne Joan Elliott-Said a.k.a. Poly-Styrene, another legendary woman of color, punk rock innovator, and singer of the classic British punk band X-Ray Spex, expressed when she sang following lyrics: “When you look in the mirror/ Do you see yourself/ Do you see yourself/ On the T.V. screen/ Do you see yourself/ In the magazine” (“Identity” X-Ray Spex).

Pérez holds up a mirror to all the weirdo outsiders, all the underrepresented youth who are made to not fit in, and shows them a story that reflects and honors their truth. She takes on the complexities and messiness of culture and identity construction, doing justice to this tough work of self-fashioning by presenting to us the diverse ingredients that combine in such a way to produce a beautifully vibrant, brave, and rad punk rock twelve-year-old girl, Malú. Most importantly, Pérez shows us the significance of our elders, our teachers who assume different roles in guiding us, and guiding Malú, to always “stand up for what she believes in, what comes from here,” her/our corazón (Pérez 190).

Malú is a second-generation, avid reader, and bicultural kid (Mexican on her mom’s side, Punk on her dad’s side), who has to contend with starting a new school in a new town, making new friends, and dealing with her mom’s fussing over her non-señorita fashion style. She moves to Chicago with her mother who (in the type of first-generation aspirational splendor so integral to our Chicanx cultural capital that many of us will surely recognize) will begin a two-year visiting professorship. Malú dances away her last night in Gainesville to The Smith’s Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want with her dad, an old punk rocker who owns Spins and Needles, a records store. She brings with her handy zine supplies to chase away the homesick blues, creating zines and surrendering her anxieties to her worry dolls.

On the first day of school, Malú puts on her best punk rock fashion armor: green jeans, Blondie tee, trenzas, silver-sequined Chucks in homage to the OG Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz, and some real heavy black eyeliner and dark lipstick, yeah! Of course, she gets called out. First, by her mom who tells her she looks like a Nosferatu(!), and then by the popular Selena Ramirez, her nemesis, who calls her weird, and then by the school policy, which lands Malú in the auditorium full of all the other kids who also stick out. Pérez captures the sticky reality of socialization where school serves as an agent of assimilation. She renders this moment with a tender humor that grateful adult eyes can point to when dealing with our children who will also likely experience this rite of passage. Malú resists being boxed in. She doesn’t want to assimilate. She doesn’t want to be “normal,” and neither does her friend Joe, whose bright blue hair and Henry Huggins steelo communicates an affinity with Malú’s punk aesthetic.

Thus, Pérez sets the stage. Malú, and her Yellow-Brick-Road crew comprised of Joe, Benny (trumpet player for the youth mariachi group), and Ellie (burgeoning activist and college-bound), are all Posada Middle School kids brought together by Malú’s vision and verve to start a punk band to debut at the school’s upcoming anniversary fiesta and talent show. Rejected, some would say censored, for not fitting into Principal Rivera’s definition of traditional Mexican family-friendly fun that she intends for the fiesta, The Co-Co’s decide to put on their own Do-It-Yourself talent show. Dubbed Alterna-Fiesta, The Co-Co’s plan to feature themselves and all the other students rejected from the school showcase for not fitting the mold.

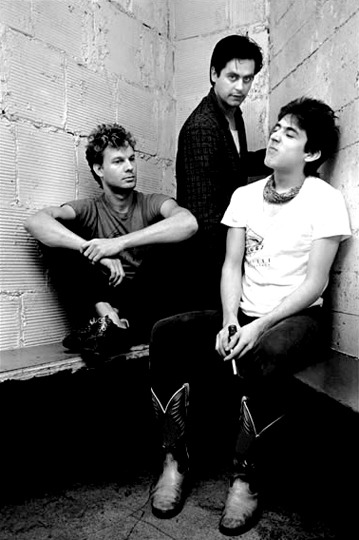

The Plugz

Ritchie Valens

The self-reliance of D.I.Y. ethos, however, does not overshadow the importance of collectivism and solidarity that supports Malú’s response and agency toward expression. Again, she has her elders to thank. Mrs. Hidalgo helps set up the Alterna-Fiesta stage, which they improvised outside the school directly following the “official” talent show. Señora Oralia, Joe’s grandmother and Mrs. Hidalgo’s mom, turns Malú on to the power of Lola Beltrán, whose rendition of “Cielito Lindo” Malú transforms into a punked-out version in the tradition of Chicanx musical culture—from Ritchie Valens to The Plugz—that fuses traditional Mexican songs with rock and roll. Even Malú’s mom, who often projects her notions of what Malú should look and be like, is also the source of an important lesson. She teaches Malú about her abuelo Refugio Morales who came to the U.S. as a Bracero, and about her abuela Aurelia González de Morales who migrated to the U.S. at sixteen years old. She helps Malú see her grandparents’ experiences reflected in her own day-to-day life in Chicago.

Malú recognizes her family’s story of migration in the lives of her peers at Posada Middle School who might be recent immigrants. She reflects upon today’s workers, whose hands, like those of her grandfather, pick the strawberries she sees in the supermarket. Through zine-making, Malú makes sense of her world. She synthesizes the new information she’s learned about her family history to create new knowledge, as documented by her zine: “Braceros like my abuelo worked with their arms … and their hands manos (Abuelo’s tools). I work with my hands, too. Not in a hard way like Abuelo. But we both create (my tools) … scissors, paper, glue stick, markers, stack of old magazines, copy machine” (Pérez 116-117). Through the creative process of making zines, Malú weaves herself into her family’s tapestry of lived experiences, values, and character that are collectively shaped by her family. Malú’s Bracero zine exemplifies what Chicana artist Carmen Lomas Garza describes as the resilient function of art, which works to heal the wounds of discrimination and racism faced by Mexican Americans—a history that is also part of Malú cultural DNA (Garza 19). Her Bracero zine is an act of resilience through art. It reflects a creative process tied to collective memory. Indeed, she calls upon herself, and by extension, her reader, to remember. For it is the act of remembering and honoring who and where we come from that enables us to integrate and construct our present lives.

Malú’s family tapestry also includes her father, who despite being geographically far away, is firmly present throughout Malú’s journey. Malú seeks his counsel after Selena calls her a coconut, i.e. brown on the outside, white on the inside. Selena, the popular girl at Posada Middle School, embodies all of the right “Mexican” elements that Malú does not. She’s dances zapateado competitively, speaks Spanish with ease, and dresses like a señorita. Confused and hurt by Selena’s insult, Malú, being the daughter of a true punk rocker, flips the insult around and turns it into the name of her band, The Co-Co’s. The move, like her father said, is subversive. And it’s transformative as it addresses how divisions happen within our culture where demarcations of who is “down” or more “Mexican” often mimic the very stereotypes that we fight against. And it’s her father’s guidance to always be herself that equips her to resist the identity boxes that try to confine her. Malú, through the course of this story, figures out her identity by shaping, combining, fashioning—even dying her hair green in homage to the Quetzal—and harmonizing all the parts of herself to create an identity that fits her just right.

The First Rule of Punk is outstanding in its ability to show authentically how children deal with the complexities and intersections of cultural identity. It reminds us of what Ghiso et al. interrogate in their study of intergroup histories as rendered in children’s literature. As children’s literature invites young people to use its narrative sites to engage the intellect in imagination and contemplation, the researchers ask, “whether younger students have the opportunity to transact with books that represent and raise questions about shared experiences and cooperation across social, cultural, and linguistic boundaries” (Ghiso et al. 15). The First Rule of Punk responds affirmatively to this question in its resplendent example of our connected cultures and collective experiences. Malú, in making whole all the parts that comprise her identity, models for us, the reader, our own interbeing, our own interconnection. It’s like she’s asking us: “Wanna be in my band?” I know I do! Do you?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: (from her website): Inspired by punk and her love of writing, Celia C. Pérez has been making zines for longer than some of you have been alive. Her favorite zine supplies are her long-arm stapler, glue sticks, animal clip art (to which she likes adding speech bubbles), and watercolor pencils. She still listens to punk music, and she’ll never stop picking cilantro out of her food at restaurants. Her zines and writing have been featured in The Horn Book Magazine, Latina, El Andar, Venus Zine, and NPR’s Talk of the Nation and Along for the Ride. Celia is the daughter of a Mexican mother and a Cuban father. Originally from Miami, Florida, she now lives in Chicago with her family and works as a community college librarian. She owns two sets of worry dolls because you can never have too many. The First Rule of Punk is her first book for young readers.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: (from her website): Inspired by punk and her love of writing, Celia C. Pérez has been making zines for longer than some of you have been alive. Her favorite zine supplies are her long-arm stapler, glue sticks, animal clip art (to which she likes adding speech bubbles), and watercolor pencils. She still listens to punk music, and she’ll never stop picking cilantro out of her food at restaurants. Her zines and writing have been featured in The Horn Book Magazine, Latina, El Andar, Venus Zine, and NPR’s Talk of the Nation and Along for the Ride. Celia is the daughter of a Mexican mother and a Cuban father. Originally from Miami, Florida, she now lives in Chicago with her family and works as a community college librarian. She owns two sets of worry dolls because you can never have too many. The First Rule of Punk is her first book for young readers.

To read a Q & A with the author, click here.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Lettycia Terrones is a doctoral student in the Department of Information Sciences at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she researches Chicanx picturebooks as sites of love and resilient resistance. She’s from East L.A. Boyle Heights.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Lettycia Terrones is a doctoral student in the Department of Information Sciences at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she researches Chicanx picturebooks as sites of love and resilient resistance. She’s from East L.A. Boyle Heights.

Works Cited

The Brat. Attitudes. Fatima Records, 1980.

Pérez, Célia. C. The First Rule of Punk. New York, Viking, 2017.

Garza, Carmen Lomas. Pedacito De Mi Corazón. Austin, Laguna Gloria Art Museum, 1991.

Ghiso, Maria Paula, Gerald Campano, and Ted Hall. “Braided Histories and Experiences in Literature for Children and Adolescents.” Journal of Children’s Literature, vol. 38, no.2, 2012, pp. 14-22.

Stevens, Heidi. “Chicago Librarian Captures Punk Aesthetic, Latino Culture in New Kids’ Book.” Chicago Tribune, 23 August 2017. chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/stevens/ct-life-stevens-wednesday-first-rule-of-punk-0823-story.html . Accessed 25 August 2017.

X-Ray Spex. “Identity.” Germfree Adolescents, EMI, 1978.

Celia C. Pérez

Celia C. Pérez Cindy L. Rodriguez

Cindy L. Rodriguez

About the author: Angela Cervantes was born and raised in Kansas. Most of her childhood was spent in Topeka, Kansas living in the Mexican-American community of Oakland. Her family also spent a lot of time in El Dorado and Wichita visiting a slew of aunts, uncles and cousins on weekends.

About the author: Angela Cervantes was born and raised in Kansas. Most of her childhood was spent in Topeka, Kansas living in the Mexican-American community of Oakland. Her family also spent a lot of time in El Dorado and Wichita visiting a slew of aunts, uncles and cousins on weekends. About the illustrator: Raised in Mexico City, Rafael López makes his home part of the year in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, as well as in San Diego, California. He credits Mexican surrealism as a major artistic influence. Besides his Pura Belpré medals and honors, Rafael is also a double recipient of the Américas Award. For more about his work, including poster illustrations and a mural project in San Diego that is the subject of a new picture book, Maybe Something Beautiful, visit his

About the illustrator: Raised in Mexico City, Rafael López makes his home part of the year in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, as well as in San Diego, California. He credits Mexican surrealism as a major artistic influence. Besides his Pura Belpré medals and honors, Rafael is also a double recipient of the Américas Award. For more about his work, including poster illustrations and a mural project in San Diego that is the subject of a new picture book, Maybe Something Beautiful, visit his  DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK’S BACK COVER: Justina ‘Ju’ Feliciano and her fellow seventh-grade sleuths are on the case! A sneaky vandal has damaged scenery from the middle school drama club production and the newbie detectives must catch the culprit before opening night.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK’S BACK COVER: Justina ‘Ju’ Feliciano and her fellow seventh-grade sleuths are on the case! A sneaky vandal has damaged scenery from the middle school drama club production and the newbie detectives must catch the culprit before opening night. ABOUT THE AUTHOR (

ABOUT THE AUTHOR ( ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Caissa Casarez is a proud multiracial Latina and a self-proclaimed nerd. When she’s not working for public television, Caissa loves reading, tweeting, and drinking cold brew. She especially loves books and other stories by fellow marginalized voices. She wants to help reach out to kids once in her shoes through the love of books to let them know they’re not alone. Caissa lives in St. Paul, MN, with her partner and their rambunctious cat. Follow her on Twitter & Instagram at @cmcasarez.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Caissa Casarez is a proud multiracial Latina and a self-proclaimed nerd. When she’s not working for public television, Caissa loves reading, tweeting, and drinking cold brew. She especially loves books and other stories by fellow marginalized voices. She wants to help reach out to kids once in her shoes through the love of books to let them know they’re not alone. Caissa lives in St. Paul, MN, with her partner and their rambunctious cat. Follow her on Twitter & Instagram at @cmcasarez. DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHERS: Ruthie Mizrahi and her family recently emigrated from Castro’s Cuba to New York City. Just when she’s finally beginning to gain confidence in her mastery of English—and enjoying her reign as her neighborhood’s hopscotch queen—a horrific car accident leaves her in a body cast and confined her to her bed for a long recovery. As Ruthie’s world shrinks because of her inability to move, her powers of observation and her heart grow larger and she comes to understand how fragile life is, how vulnerable we all are as human beings, and how friends, neighbors, and the power of the arts can sweeten even the worst of times.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHERS: Ruthie Mizrahi and her family recently emigrated from Castro’s Cuba to New York City. Just when she’s finally beginning to gain confidence in her mastery of English—and enjoying her reign as her neighborhood’s hopscotch queen—a horrific car accident leaves her in a body cast and confined her to her bed for a long recovery. As Ruthie’s world shrinks because of her inability to move, her powers of observation and her heart grow larger and she comes to understand how fragile life is, how vulnerable we all are as human beings, and how friends, neighbors, and the power of the arts can sweeten even the worst of times. ABOUT THE AUTHOR (

ABOUT THE AUTHOR ( ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Maria Ramos-Chertok is a writer who lives in Mill Valley, CA. She is the founder and facilitator of The Butterfly Series, a writing and creative arts workshop for women who want to explore what’s next in their life journey. Her work, most recently, has appeared in San Francisco’s 2016 Listen to Your Mother show (www.listentoyourmothershow.com) and in the Apogee Journal of Colombia University. Her piece Meet me by the River will be published in Deborah Santana’s anthology All the Women in my Family Sing (2017) and she will be reading in San Francisco’s LitCrawl in October 2016. For more information please visit

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Maria Ramos-Chertok is a writer who lives in Mill Valley, CA. She is the founder and facilitator of The Butterfly Series, a writing and creative arts workshop for women who want to explore what’s next in their life journey. Her work, most recently, has appeared in San Francisco’s 2016 Listen to Your Mother show (www.listentoyourmothershow.com) and in the Apogee Journal of Colombia University. Her piece Meet me by the River will be published in Deborah Santana’s anthology All the Women in my Family Sing (2017) and she will be reading in San Francisco’s LitCrawl in October 2016. For more information please visit