The Pura Belpré Awards turns 20 this year! The milestone was marked on Sunday, June 26, during the 2016 ALA Annual Conference in Orlando, FL. In honor of the award’s anniversary, we have been highlighting the winners of the narrative and illustration awards. Today’s spotlight is on Viola Canales, the winner of the 2006 Pura Belpré Narrative Medal for The Tequila Worm.

Review by Cindy L. Rodriguez

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Sofia comes from a family of storytellers. Here are her tales of growing up in the barrio, full of the magic and mystery of family traditions: making Easter cascarones, celebrating el Día de los Muertos, preparing for quinceañera, rejoicing in the Christmas nacimiento, and curing homesickness by eating the tequila worm. When Sofia is singled out to receive a scholarship to an elite boarding school, she longs to explore life beyond the barrio, even though it means leaving her family to navigate a strange world of rich, privileged kids. It’s a different mundo, but one where Sofia’s traditions take on new meaning and illuminate her path.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Sofia comes from a family of storytellers. Here are her tales of growing up in the barrio, full of the magic and mystery of family traditions: making Easter cascarones, celebrating el Día de los Muertos, preparing for quinceañera, rejoicing in the Christmas nacimiento, and curing homesickness by eating the tequila worm. When Sofia is singled out to receive a scholarship to an elite boarding school, she longs to explore life beyond the barrio, even though it means leaving her family to navigate a strange world of rich, privileged kids. It’s a different mundo, but one where Sofia’s traditions take on new meaning and illuminate her path.

MY TWO CENTS: The Tequila Worm begins as vignettes and then moves into a more traditional narrative when Sofia, the Mexican-American protagonist, is a fourteen-year-old high school freshman. In the beginning, a younger Sofia relays special family-centered moments–some downright hysterical and others more poignant–such as her First Communion, making cascarones for Easter, and celebrating both Halloween and Día de los Muertos. Throughout these moments, Sofia learns about her culture and, at times, is torn between her tight-knit community and the “American” world beyond her barrio in McAllen, Texas. After trick-or-treating in her neighborhood and then in another, wealthier part of town, Sofia has this conversation with her father:

“I wish I lived on the other side of town,” I said, looking out the window at the darkness.

“Why, mi’ja?”

“Because they live in nice houses, and they’re warm.”

“Ah, but there’s warmth on this side, too.”

“But…it’s really cold at home, and most of the houses around us are falling apart.”

“Yes, but we have our music, our foods, our traditions. And the warm hearts of our families.”

Another example is when Sofia is verbally bullied, called a “Taco Head” by students when she eats her homemade lunch at school. First, she is embarrassed and avoids the cafeteria entirely, spending that time on the playground or eating inside a stall in the girls’ bathroom to avoid ridicule. With the help of a P.E. teacher, Sofia returns to the lunch room, proudly eats her tacos in public, and is given the advice to get even, not by kicking the bully (which Sofia wants to do) but by kicking her butt at school.

Sofia, indeed, excels in academics and is offered a scholarship to St. Luke’s Episcopal School, a prestigious boarding school in Austin. Sofia’s family doesn’t understand why she wants to leave her home. When her mother asks, “But what’s wrong with here?” Sofia responds, “Nothing. But the Valley is not the whole world…I just want to see what’s out there.”

Eventually, Sofia’s family allows her to attend St. Luke’s, as long as she promises to remain connected and learn how to be a good comadre to her sister Lucy and cousin Berta. In the place she calls “Another Mundo,” Sofia learns to appreciate her family’s stories and traditions, understanding how they have shaped her and connected her to a community rich in other ways. The young girl who once hid after being called a “Taco Head,” grows into a young adult who is “brave enough to eat a whole tequila worm” and who confronts a classmate who writes a note telling Sofia to “wiggle back across the border.” Sofia responds by saying, “My family didn’t cross the border; it crossed us. We’ve been here for over three hundred years, before the U.S. drew those lines.”

The novel’s end leaps ahead in time, with Sofia as an adult, a civil rights lawyer living in San Francisco, who fights to preserve her changing neighborhood and who often visits to happily participate in the traditions she questioned as a child.

The novel’s main events are closely connected to the author’s life, as she, too, was raised in McAllen and attended a prestigious boarding school before attending Harvard University. Many of Canales’s own experiences, portrayed through Sofia, would be easily recognizable to younger Latinx readers who straddle two cultures and find value in each as they come of age.

TEACHING TIPS & RESOURCES: The Tequila Worm naturally lends itself to lessons that explore Mexican-American culture–specifically cascarones, quinceañeras, and Día de los Muertos–as well as broader literary elements, such as character development and universal themes. For classroom ideas, check out these links, starting with this fabulous, thorough Educator’s Guide created by Vamos a Leer: Teaching Latin America through Literacy

A Study Guide created by teacher Bobbi Mimmack: https://sites.google.com/a/chccs.k12.nc.us/bobbi-mimmack/the-tequila-worm-by-viola-canales

An author interview in Harvard Magazine: http://harvardmagazine.com/2006/01/the-beauty-of-beans.html

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from the Stanford Law School website): Early in her career, Viola Canales served as a field organizer for the United Farm Workers and an officer in the United States Army, where she was tactical director at a Brigade Fire Distribution Center overseeing Patriot and Hawk missile systems in West Germany, and before this, a platoon leader at a Hawk missile battery. After graduating from Harvard Law School, she practiced law at O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles (while also serving as a Civil Service Commissioner for the City of Los Angeles, to which she was appointed by Mayor Tom Bradley) and San Francisco, and then headed up the westernmost region of the Small Business Administration under the Clinton Administration. Her book of short stories, Orange Candy Slices and Other Secret Tales, was published by the University of Houston’s Arte Público Press; her novel The Tequila Worm, published by Random House, was designated a Notable Book by the American Library Association, and won its Pura Belpré Medal for Narrative, as well as a PEN Center USA Award. El Gusano de Tequila – her Spanish translation of the novel – was published in 2012 by KingCake Press. Her bilingual book of poems The Little Devil & The Rose (El Diabilito y La Rosa) was published in 2014 by the University of Houston.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from the Stanford Law School website): Early in her career, Viola Canales served as a field organizer for the United Farm Workers and an officer in the United States Army, where she was tactical director at a Brigade Fire Distribution Center overseeing Patriot and Hawk missile systems in West Germany, and before this, a platoon leader at a Hawk missile battery. After graduating from Harvard Law School, she practiced law at O’Melveny and Myers in Los Angeles (while also serving as a Civil Service Commissioner for the City of Los Angeles, to which she was appointed by Mayor Tom Bradley) and San Francisco, and then headed up the westernmost region of the Small Business Administration under the Clinton Administration. Her book of short stories, Orange Candy Slices and Other Secret Tales, was published by the University of Houston’s Arte Público Press; her novel The Tequila Worm, published by Random House, was designated a Notable Book by the American Library Association, and won its Pura Belpré Medal for Narrative, as well as a PEN Center USA Award. El Gusano de Tequila – her Spanish translation of the novel – was published in 2012 by KingCake Press. Her bilingual book of poems The Little Devil & The Rose (El Diabilito y La Rosa) was published in 2014 by the University of Houston.

Cindy L. Rodriguez is a former journalist turned public school teacher and fiction writer. She was born in Chicago; her father is from Puerto Rico and her mother is from Brazil. She has degrees from UConn and CCSU and has worked as a reporter at The Hartford Courant and researcher at The Boston Globe. She and her daughter live in Connecticut, where she teaches middle school reading and college-level composition. Her debut contemporary YA novel, When Reason Breaks, released with Bloomsbury Children’s Books on 2/10/2015. She can also be found on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Cindy L. Rodriguez is a former journalist turned public school teacher and fiction writer. She was born in Chicago; her father is from Puerto Rico and her mother is from Brazil. She has degrees from UConn and CCSU and has worked as a reporter at The Hartford Courant and researcher at The Boston Globe. She and her daughter live in Connecticut, where she teaches middle school reading and college-level composition. Her debut contemporary YA novel, When Reason Breaks, released with Bloomsbury Children’s Books on 2/10/2015. She can also be found on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Cris Rhodes is a doctoral student at Texas A&M University – Commerce. She received a M.A. in English with an emphasis in borderlands literature and culture from Texas A&M – Corpus Christi, and a B.A. in English with a minor in children’s literature from Longwood University in her home state of Virginia. Cris recently completed a Master’s thesis project on the construction of identity in Chicana young adult literature.

Cris Rhodes is a doctoral student at Texas A&M University – Commerce. She received a M.A. in English with an emphasis in borderlands literature and culture from Texas A&M – Corpus Christi, and a B.A. in English with a minor in children’s literature from Longwood University in her home state of Virginia. Cris recently completed a Master’s thesis project on the construction of identity in Chicana young adult literature. The

The

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR (from her

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR (from her  Marianne Snow Campbell

Marianne Snow Campbell DESCRIPTION (from GoodReads): Dad believed people were like money. You could be a thousand-dollar person or a hundred-dollar person – even a ten-, five-, or one-dollar person. Below that, everybody was just nickels and dimes. To my dad, we were pennies.

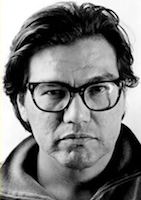

DESCRIPTION (from GoodReads): Dad believed people were like money. You could be a thousand-dollar person or a hundred-dollar person – even a ten-, five-, or one-dollar person. Below that, everybody was just nickels and dimes. To my dad, we were pennies. Victor Martinez was born and raised in Fresno, California, the fourth in a family of twelve children. He attended California State University at Fresno and Stanford University, and has worked as a field laborer, welder, truck driver, firefighter, teacher, and office clerk. His poems, short stories, and essays have appeared in journals and anthologies. Mr. Martinez was awarded the 1996 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for Parrot in the Oven, his first novel. Mr. Martinez lived in San Francisco, California, where he helped to found the poetry collective Humanizarte. He passed away in 2011.

Victor Martinez was born and raised in Fresno, California, the fourth in a family of twelve children. He attended California State University at Fresno and Stanford University, and has worked as a field laborer, welder, truck driver, firefighter, teacher, and office clerk. His poems, short stories, and essays have appeared in journals and anthologies. Mr. Martinez was awarded the 1996 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for Parrot in the Oven, his first novel. Mr. Martinez lived in San Francisco, California, where he helped to found the poetry collective Humanizarte. He passed away in 2011. Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington DC where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington DC where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at  DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Doña Flor is a giant lady who lives in a tiny village in the American Southwest. Popular with her neighbors, she lets the children use her flowers as trumpets and her leftover tortillas as rafts. Flor loves to read, too, and she can often be found reading aloud to the children.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Doña Flor is a giant lady who lives in a tiny village in the American Southwest. Popular with her neighbors, she lets the children use her flowers as trumpets and her leftover tortillas as rafts. Flor loves to read, too, and she can often be found reading aloud to the children. Dr. Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez’s research focuses on the various roles that healing plays in Latinx children’s and young adult literature. She currently teaches composition and literature at a community college in Chicago. She also teaches poetry to 6th graders and drama to 2nd graders as a teaching artist through a local arts organization. She is working on her middle grade book. Follow Sonia on Instagram @latinxkidlit

Dr. Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez’s research focuses on the various roles that healing plays in Latinx children’s and young adult literature. She currently teaches composition and literature at a community college in Chicago. She also teaches poetry to 6th graders and drama to 2nd graders as a teaching artist through a local arts organization. She is working on her middle grade book. Follow Sonia on Instagram @latinxkidlit DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Every year, Eric spends his winter break with his grandmother in El Barrio while his parents are at work. There’s much to do to prepare for Christmas, including buying all the ingredients for Grandma’s famous pasteles, a special Puerto Rican holiday dish.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Every year, Eric spends his winter break with his grandmother in El Barrio while his parents are at work. There’s much to do to prepare for Christmas, including buying all the ingredients for Grandma’s famous pasteles, a special Puerto Rican holiday dish.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR: Eric Velasquez is an Afro-Puerto Rican illustrator born in Spanish Harlem. He attended the High School of Art and Design, the School of Visual Arts, and the famous Art Students League in New York City. As a children’s book illustrator, Velasquez has collaborated with many writers, receiving a nomination for the 1999 NAACP Image Award in Children’s Literature and the 1999 Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award for New Talent for The Piano Man. For more information, and to view a gallery of his beautiful book covers, visit

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR: Eric Velasquez is an Afro-Puerto Rican illustrator born in Spanish Harlem. He attended the High School of Art and Design, the School of Visual Arts, and the famous Art Students League in New York City. As a children’s book illustrator, Velasquez has collaborated with many writers, receiving a nomination for the 1999 NAACP Image Award in Children’s Literature and the 1999 Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award for New Talent for The Piano Man. For more information, and to view a gallery of his beautiful book covers, visit  Lila Quintero Weaver

Lila Quintero Weaver