DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Tula is a girl who yearns for words, who falls in love with stories, but in Cuba, girls are not allowed an education. No, Tula is expected to marry well—even though she’s filled with guilt at the thought of the slaves Mamá will buy with the money gained by marrying Tula to the highest bidder.

Then one day, hidden in the dusty corner of a convent library, Tula discovers the banned books of a rebel poet. The poems speak to the deepest part of her soul, giving her a language with which to write of the injustice around her. In a country that isn’t free, the most daring abolitionists are poets who can veil their work with metaphors, and Tula becomes just that.

In powerful, haunting verses of her own, Margarita Engle evokes the voice of Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda, known as Tula, a young woman who was brave enough to speak up for those who could not.

MY TWO CENTS: The novel begins in 1827. Tula’s mother, who twice made the mistake of marrying for love, is desperate to prevent her thirteen-year-old daughter from taking a similar path. Mamá’s motivations are clear-cut. A wealthy connection through Tula is the family’s only hope for propping up their shaky economic status. In 19th-century colonial Cuba, arranged marriages are the social norm, but Tula’s mother worries that a girl who buries her nose in books will not attract the right kind of husband–a rich one.

Who is Tula? Margarita Engle is acclaimed for novels in verse that bring to life history’s outliers, young men and women from previous centuries who thought and acted in surprisingly modern ways, and Tula stands tall among them. She’s based on Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda, a Cuban poet who championed liberty for all humans and wrote Sab, an abolitionist novel, the first of its kind in Spanish. Sab predated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the Harriet Beecher Stowe classic, by eleven years. Avellaneda’s importance as an abolitionist and feminist writer is not widely known in English-speaking America. The Lightning Dreamer corrects this oversight and imagines Avellaneda’s formative years, just as she began to discover the life-changing force of poetry.

Marriageability is not the only issue that arises from Tula’s penchant for reading. She happens upon the forbidden poetry of José María Heredia, whose sharp observations awaken Tula’s passion for justice. In colonial Cuba, injustice is everywhere. Her eyes take in the plight of African slaves, biracial babies abandoned to the convent, lovers kept apart by miscegenation taboos, and girls like herself, doomed to business arrangements thinly masquerading as marriages. Tula expresses her ardor for justice through poetry, which she burns to keep her mother from discovering.

When Tula refuses the marriage that her grandfather arranges, she must rise to meet a string of new challenges. The inheritance is lost and her family is condemned to relative poverty. For a while, Tula finds refuge in a storyteller’s community, where she becomes entangled in an unrequited love. She moves away from the countryside to Havana, where she supports herself through tutoring. In 1836, her brother, Manuel, warns her that their mother is cooking up another arranged match. Tula flees for Spain, expecting to find greater social and creative freedom there.

The Lightning Dreamer is written in free verse and is voiced through multiple characters. Tula is the most frequent speaker. Short segments provide other characters’ point of view. A partial list includes Tula’s mother; Manuel; Caridad, the freed slave who works for the family; the nuns who offer Tula space to read and write in peace; and Sab. Each character speaks in first person. I imagine them as a series of stage players delivering brief and sometimes prejudicial monologues reflecting on Tula’s choices. This approach perfectly suits the fictionalized treatment of a young poet. The language is spare and often stunning, capturing vivid images and profound interiority, as in this excerpt:

When we visit my grandfather

on his sugar plantation,

I see how luxurious

my mother’s childhood

must have been,

surrounded by beautiful

emerald green sugar fields

harvested

by row after row

of sweating slaves.

How can one place

be so lovely

and so sorrowful

all at the same time?

READING LEVEL: 12 and up

TEACHING TIPS: The Lightning Dreamer is an ideal jumping off point for exploring a wide array of subjects suggested in the novel. These range from colonialism, to New World slavery and racism, to patriarchal societies and the history of women’s political movements. At the back of the book, extensive notes provide comparisons between the historical Avellaneda and Tula, her fictionalized counterpart. This section also includes Spanish and translated excerpts of Avellaneda’s poetry and a bibliography of related sources.

Margarita contributed a guest post to Latin@s in Kid Lit that illuminates her love of biographical writing.

Henry Louis Gates’ PBS series, Black in Latin America, may be of interest for classroom use, in conjunction with the reading of The Lightning Dreamer. The episode “Cuba: The Next Revolution” focuses on the ongoing struggle by Afro Cubans to overcome centuries of racism. There’s no mention of Avellaneda in this one-hour documentary film; nevertheless, interviews and scenery enriched my reading. The film is particularly effective in its treatment of Cuba’s history of slavery and the role of freed slaves in the protracted battle for independence from Spain. The ruins of sugar plantations dating back to the book’s era starkly reminded me of Tula’s world.

RECOGNITION FOR THE LIGHTNING DREAMER: Awards and honors continue to flood in. They include:

2014 Pura Belpré Honor Book

School Library Journal’s Top Ten Latino-themed Books for 2013

YALSA 2014 Best Fiction for Young Adults

For a full list of awards and more information, please visit Margarita’s author website. I also recommend following her on Facebook, where she frequently posts updates on appearances, interviews and release dates for new books.

THE AUTHOR: Margarita Engle is a native of California and the author of many children’s and young adult books. She is the daughter of an American father and a Cuban mother. Childhood visits to her extended family in Cuba influenced her interest in tropical nature, leading to her formal study of agronomy and botany. She is the winner of the first Newbery Honor ever awarded to a Latino/a. Her award winning young adult novels in verse include The Surrender Tree, The Poet Slave of Cuba, Tropical Secrets, and The Firefly Letters.

THE AUTHOR: Margarita Engle is a native of California and the author of many children’s and young adult books. She is the daughter of an American father and a Cuban mother. Childhood visits to her extended family in Cuba influenced her interest in tropical nature, leading to her formal study of agronomy and botany. She is the winner of the first Newbery Honor ever awarded to a Latino/a. Her award winning young adult novels in verse include The Surrender Tree, The Poet Slave of Cuba, Tropical Secrets, and The Firefly Letters.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT The Lightning Dreamer, visit your local library or bookstore. Also check out worldcat.org, indiebound.org, goodreads.com, amazon.com, barnesandnoble.com, and Houghton Mifflin/Harcourt.

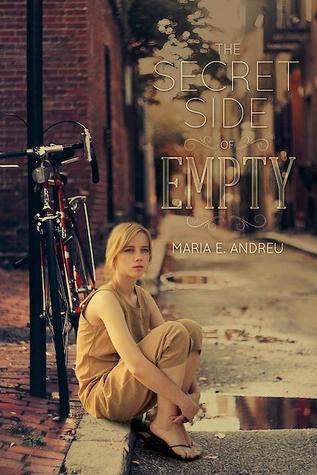

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: M.T. is undocumented. But she keeps that a secret. As a straight-A student with a budding romance and loyal best friend, M.T.’s life seems as apple-pie American as her blondish hair and pale skin. But she hides two facts to the contrary: her full name of Monserrat Thalia and her status as an undocumented immigrant.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: M.T. is undocumented. But she keeps that a secret. As a straight-A student with a budding romance and loyal best friend, M.T.’s life seems as apple-pie American as her blondish hair and pale skin. But she hides two facts to the contrary: her full name of Monserrat Thalia and her status as an undocumented immigrant.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Set in the Pilsen barrio of Chicago, this children’s picture book gives a heartwarming message of hope. The heroine, América, is a primary school student who is unhappy in school until a poet visits the class and inspires the students to express themselves creatively–in Spanish or English. América Is Her Name emphasizes the power of individual creativity in overcoming a difficult environment and establishing self-worth and identity through the young girl América’s desire and determination to be a writer. This story deals realistically with the problems in urban neighborhoods and has an upbeat theme: you can succeed in spite of the odds against you. Carlos Vázquez’s inspired four-color illustrations give a vivid sense of the barrio, as well as the beauty and strength of the young girl América.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Set in the Pilsen barrio of Chicago, this children’s picture book gives a heartwarming message of hope. The heroine, América, is a primary school student who is unhappy in school until a poet visits the class and inspires the students to express themselves creatively–in Spanish or English. América Is Her Name emphasizes the power of individual creativity in overcoming a difficult environment and establishing self-worth and identity through the young girl América’s desire and determination to be a writer. This story deals realistically with the problems in urban neighborhoods and has an upbeat theme: you can succeed in spite of the odds against you. Carlos Vázquez’s inspired four-color illustrations give a vivid sense of the barrio, as well as the beauty and strength of the young girl América.