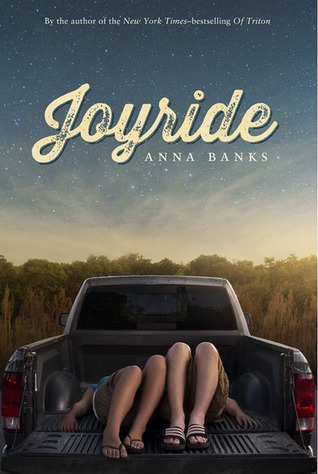

PUBLISHER’S DESCRIPTION: A popular guy and a shy girl with a secret become unlikely accomplices for midnight pranking, and are soon in over their heads—with the law and with each other—in this sparkling standalone from NYT-bestselling author Anna Banks.

It’s been years since Carly Vega’s parents were deported. She lives with her brother, studies hard, and works at a convenience store to contribute to getting her parents back from Mexico.

Arden Moss used to be the star quarterback at school. He dated popular blondes and had fun with his older sister, Amber. But now Amber’s dead, and Arden blames his father, the town sheriff who wouldn’t acknowledge Amber’s mental illness. Arden refuses to fulfill whatever his conservative father expects.

All Carly wants is to stay under the radar and do what her family expects. All Arden wants is to NOT do what his family expects. When their paths cross, they each realize they’ve been living according to others. Carly and Arden’s journey toward their true hearts—and one another—is funny, romantic, and sometimes harsh.

MY TWO CENTS: In Joyride, Anna Banks creates two easily likable, sympathetic characters who are struggling between wanting to have normal, fun teenage lives and dealing with serious family issues.

Carly Vega is a smart, hard working Mexican-American teen who juggles going to school and working, sometimes until the early morning hours at a convenient store, to help raise enough money to bring her deported, undocumented parents back to the U.S.

Arden is a popular former football star who battles with his violent father in the wake of his sister’s suicide, which has left his mother heavily medicated and despondent.

In the opening scene, Arden pretends to hold up his uncle, Mr. Shackelford, outside the convenient store in an attempt to get him to stop driving drunk. Carly, who is working when this happens, responds by pulling out the store owner’s shotgun and chasing the masked bandit (Arden) off. Arden knows then that Carly is the perfect candidate to be his pranking buddy, a position once held by his sister. Love blossoms as the two spend more time together doing funny, gross things around town that are risky because Arden’s father is the racist local sheriff responsible for deporting Carly’s parents.

Throughout the novel, Carly struggles with competing desires. She wants her family to be intact again and wants to do all she can to help raise the thousands of dollars needed to help them cross the border again. She also wants, however, to do what normal teen girls do, like hang out with her boyfriend and use her money to buy things like new clothes and a laptop computer.

Without giving too much away, I’ll say that this YA contemporary, which tackles serious issues and has heavy doses of romance and humor, also has a plot twist that adds a whole new exciting vibe to the story. Carly and Arden’s relationship is threatened and they end up in a dangerous situation involving law enforcement and the illegal smuggling operation that promises to bring her parents home.

Told in alternating points of view–Carly’s is first person and Arden’s is third–Anna Banks’s Joyride is a page-turner filled with interesting, complex characters who fall in love and find common ground despite economic, racial, and cultural differences.

TEACHING TIPS: Joyride could be an option when teaching about immigration. I’m sure students would have lots of questions about the issues brought up with this book around Carly’s family’s situation. Do people really pay someone to escort loved ones across the border? What are the risks? Is it really that expensive? What happens if they get caught again? How often are American born teens separated from parents who are deported? Reading this novel as a companion to non-fiction research on these issues could offer multiple perspectives and make Carly Vega seem even more “real,” in that her situation is a common one.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from her website): NYT Bestselling YA author of The Syrena Legacy series: OF POSEIDON (2012) OF TRITON (2013) OF NEPTUNE (2014). Repped by rockstar Lucy Carson of the Friedrich Agency. I live with my husband and daughter in the Florida Panhandle. I have a southern accent compared to New Yorkers, and I enjoy food cooked with real fat. I can’t walk in high heels, but I’m very good at holding still in them. If you put chocolate in front of me, you must not have wanted it in the first place.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from her website): NYT Bestselling YA author of The Syrena Legacy series: OF POSEIDON (2012) OF TRITON (2013) OF NEPTUNE (2014). Repped by rockstar Lucy Carson of the Friedrich Agency. I live with my husband and daughter in the Florida Panhandle. I have a southern accent compared to New Yorkers, and I enjoy food cooked with real fat. I can’t walk in high heels, but I’m very good at holding still in them. If you put chocolate in front of me, you must not have wanted it in the first place.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT Joyride visit your local library or bookstore. Also, check out WorldCat.org, IndieBound.org, Goodreads, Amazon, and Barnes & Noble.

Also, check out the Q&A we did with Anna Banks earlier this week.

FROM THE PUBLISHER:

FROM THE PUBLISHER:

ncing good intentions and generosity to others with responsibility and a concern for appearances. When Señora Beatriz sends Pepe out for lunch on their first day together, Melky, one of the street boys, recognizes him and runs over to join him. Pepe becomes preoccupied with Melky’s disheveled appearance, worrying that the señora might think he is a street boy, too, if she sees him with Melky. Pepe understands the boy’s hungry glances at the lunch bag, but his fear over damaging his opportunity with Señora Beatriz is what drives him to share his food: “If I give you some of my lunch, you have to promise to go away. You can’t let the señora see you—ever!” (33).

ncing good intentions and generosity to others with responsibility and a concern for appearances. When Señora Beatriz sends Pepe out for lunch on their first day together, Melky, one of the street boys, recognizes him and runs over to join him. Pepe becomes preoccupied with Melky’s disheveled appearance, worrying that the señora might think he is a street boy, too, if she sees him with Melky. Pepe understands the boy’s hungry glances at the lunch bag, but his fear over damaging his opportunity with Señora Beatriz is what drives him to share his food: “If I give you some of my lunch, you have to promise to go away. You can’t let the señora see you—ever!” (33). ove with the beautiful fabrics and deck themselves out in tiaras and veils. Primo succeeds at fixing the sewing machine, but the boys are so tired from their efforts they fall asleep at the kitchen table.

ove with the beautiful fabrics and deck themselves out in tiaras and veils. Primo succeeds at fixing the sewing machine, but the boys are so tired from their efforts they fall asleep at the kitchen table.

By Kimberly Mach

By Kimberly Mach Kimberly Mach has been teaching for sixteen years and holds two teaching certificates in elementary and secondary education. Her teaching experience ranges from grades five to twelve, but she currently teaches Language Arts to middle school students. It is a job she loves. The opportunity to share good books with students is one that every teacher should have. She feels privileged to be able to share them on a daily basis.

Kimberly Mach has been teaching for sixteen years and holds two teaching certificates in elementary and secondary education. Her teaching experience ranges from grades five to twelve, but she currently teaches Language Arts to middle school students. It is a job she loves. The opportunity to share good books with students is one that every teacher should have. She feels privileged to be able to share them on a daily basis.

By Marianne Snow

By Marianne Snow