This year marks the 20th anniversary of the Pura Belpé Awards. Starting in the spring, we began shining a spotlight on the winners. This post features the beautiful and imaginative illustration work of Stephanie Garcia for Snapshots from the Wedding, a delightful picture book written by Gary Soto, and the winner of the 1998 Pura Belpré Illustration Award.

Review by Lila Quintero Weaver

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Meet Maya, Isabel’s flower girl, as she describes in vivid detail the exciting wedding day. Maya introduces us to Danny, the ring bearer; Aunt Marta, crying big tears; Uncle Trino, jump-starting a car in his tuxedo; and Rafael, the groom, with a cast on his arm. Of course, the big day also includes games, dancing, cake, and a mariachi band that plays long into an evening no one will ever forget.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Meet Maya, Isabel’s flower girl, as she describes in vivid detail the exciting wedding day. Maya introduces us to Danny, the ring bearer; Aunt Marta, crying big tears; Uncle Trino, jump-starting a car in his tuxedo; and Rafael, the groom, with a cast on his arm. Of course, the big day also includes games, dancing, cake, and a mariachi band that plays long into an evening no one will ever forget.

Snapshots from the Wedding captures the unique moments of a special occasion—the big scenes as well as the little ones—that together form a rich family mosaic.

MY TWO CENTS: Snapshots from the Wedding is a lightly humorous story told through the eyes of a young girl named Maya. Gary Soto delivers this joyous narrative of a traditional Mexican boda in lyrical and rhythmic language.

By casting Maya in the role of narrator, Soto allows the reader the same view of the festivities as a member of the wedding party. From her position, Maya observes and comments on the assembled guests, the bridal procession, the photographer at work, and the moment when the couple exchanges vows at the altar. Afterward, at the reception, Maya revels in the mariachi band, the pinning of paper money to the bride’s skirt, and the couple’s departure beneath a shower of rice. As her gaze travels across each scene, she stops to focus on details ranging from the ring bearer’s slicked-back hair, to a boy whose tongue wiggles through the space left by newly lost baby teeth, and to the eye-popping spectacle of a towering wedding cake.

In Soto’s words, “Here’s the wedding cake, seventh wonder of the world, from Blanco’s Bakery, with more frosting than a mountain of snow, with more roses than mi abuela’s back yard, with more swirls than a hundred turns on a merry-go-round.”

Stephanie Garcia, the Pura Belpré-winning illustrator, depicts Maya’s wide-eyed experience of the wedding as something remembered through a series of winsome snapshots. Yet, in one of the most surprising and original aspects of this book, Garcia brings the scenes into sharp relief through exquisitely constructed dioramas that defy all expectations for a story conceived around the idea of photographs.

Each of the three-dimensional illustrations is a miniature stage that sits within a shallow wooden box. The overall effect is that of a dollhouse whose rooms brim with texture and engaging detail, and which cry out to be touched and played with, in order to fully appreciate the tactile gifts they offer. Using a wide range of materials that includes fabric, clay, paint, and found objects, Garcia populates her scenes with individually rendered characters, furnishings, and backdrops. Fashioned from Sculpy clay, each human figure bears distinct facial features and expressions. The skin tones come in varied shades of brown, and each is dressed in clothing suitable for that person’s role in the wedding.

By leaving the diorama’s rough wooden edges in full view and by dressing some of the wedding guests in homespun fabrics, the book hints at the deeper, economic realities of life in a working-class Mexican community. Yet, the momentous social importance of weddings often leads families to go all out for the occasion, evidenced here by the elaborate costumes of the mariachi band and the satin-and-lace gowns of the bridal party.

In nearly every spread, Garcia employs a clever frame-within-a-frame concept that plays with the passage of time. In these instances, select characters appear inside a gilt-edged frame, like mannequins propped in a store window, even as the activity of the moment continues to swirl around them. This approach suggests a future glimpse of the photos being taken. Appropriately, the photographer himself appears in one of the dioramas, snapping his shutter just as the bride and groom are about to kiss.

Garcia’s attention to individual characters complements Soto’s depictions. In one of my favorite vignettes, little Maya and another young lady try their best to snare the bouquet as the bride tosses it. But the bouquet is “caught by the tallest woman there, my cousin Virginia, a college basketball player, with a three-foot vertical leap.” Garcia gives Virginia a mint-green bridesmaid’s dress, with low-heel pumps dyed to match, and a long reach that ensures her effortless catch. We can easily imagine Virginia in a basketball uniform, putting her vertical leap to good use in a different context.

With such singular moments, Soto and Garcia illuminate a range of experiences not often captured in portrayals of Mexican culture. Through its engaging text and rich dioramas, this picture book offers charming views of an important social occasion as seen through the delighted eyes of a little girl who feels at home within this community. And this wedding is an occasion she’ll remember for years to come through its album of snapshots.

Note: We were not able to secure permission from the publisher to share images from the book’s interior pages. Please locate a copy and see them for yourself!

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Stephanie Garcia is an illustrator, graphic designer, art director, and design consultant, with a wealth of experience in the corporate world and the classroom, where she shares her knowledge with others. Learn more about her in this publisher profile.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Stephanie Garcia is an illustrator, graphic designer, art director, and design consultant, with a wealth of experience in the corporate world and the classroom, where she shares her knowledge with others. Learn more about her in this publisher profile.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Gary Soto is the author of multiple picture books, including the Chato series, which won the Pura Belpré illustrator award for Susan Guevara. He also published many novels for youth, as well as books of short stories for young readers, and collections of essays and poems. His awards include the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, the Andrew Carnegie Medal, and the National Book Award. Learn more at his official website. See some of our coverage of Soto’s work in this review and in a post about his decision to stop publishing children’s literature.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Gary Soto is the author of multiple picture books, including the Chato series, which won the Pura Belpré illustrator award for Susan Guevara. He also published many novels for youth, as well as books of short stories for young readers, and collections of essays and poems. His awards include the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, the Andrew Carnegie Medal, and the National Book Award. Learn more at his official website. See some of our coverage of Soto’s work in this review and in a post about his decision to stop publishing children’s literature.

Lila Quintero Weaver is the author-illustrator of Darkroom: A Memoir in Black & White. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Darkroom recounts her family’s immigrant experience in small-town Alabama during the tumultuous 1960s. It is her first major publication. Her next book is a middle-grade novel scheduled for release in 2018 (Candlewick). Lila is a graduate of the University of Alabama. She and her husband, Paul, are the parents of three grown children. She can also be found on her own website, Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

Lila Quintero Weaver is the author-illustrator of Darkroom: A Memoir in Black & White. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Darkroom recounts her family’s immigrant experience in small-town Alabama during the tumultuous 1960s. It is her first major publication. Her next book is a middle-grade novel scheduled for release in 2018 (Candlewick). Lila is a graduate of the University of Alabama. She and her husband, Paul, are the parents of three grown children. She can also be found on her own website, Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

“Coaches” or “mentors” have been crucial for the development of mankind since time immemorial. Older or wiser men and women took young wards under their wings to teach them hunting and gathering edible plants, or to pass down traditions important for survival. The concept was crystallized in ancient Greece, when Mentor, a friend of King Odysseus, stayed behind to take care of the king’s son, Telemachus. The boy and Mentor developed a trusted friendship, one whose importance can be observed in centuries of literature and movies. Think Arthur and Merlin. Leonardo Da Vinci and Raphael Sanzio. Or Daniel and Mr. Miyagi.

“Coaches” or “mentors” have been crucial for the development of mankind since time immemorial. Older or wiser men and women took young wards under their wings to teach them hunting and gathering edible plants, or to pass down traditions important for survival. The concept was crystallized in ancient Greece, when Mentor, a friend of King Odysseus, stayed behind to take care of the king’s son, Telemachus. The boy and Mentor developed a trusted friendship, one whose importance can be observed in centuries of literature and movies. Think Arthur and Merlin. Leonardo Da Vinci and Raphael Sanzio. Or Daniel and Mr. Miyagi.

Ana writes: “This cover design was created in watercolor, inks and gouache. I’m so happy to share with everyone the face of an unknown, mysterious and mischievous creature: the chupacabra!”

Ana writes: “This cover design was created in watercolor, inks and gouache. I’m so happy to share with everyone the face of an unknown, mysterious and mischievous creature: the chupacabra!”

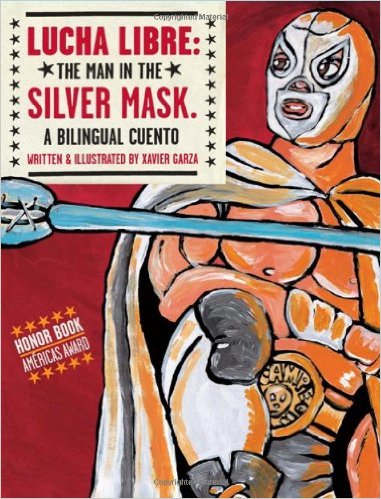

By Xavier Garza

By Xavier Garza But there was another reason I wrote books about luchadores, dating back to when I was a seven-year-old child going to the movies with my dad. It was the summer of 1974 when my father took me to the H&H Drive-In in my hometown of Rio Grande City, Texas. The marquee heralded a double-feature matinee that consisted of a Japanese monster movie and an action-thriller flick from the world of Mexican cinema. The second film was titled Santo contra las momias de Guanajuato (The Saint versus the Mummies of Guanajuato). I was all too familiar with radioactive fire-breathing Japanese Kaijua monster movies of the Godzilla variety, but up until that night, I had not yet been introduced to the masked heroes and villains of lucha libre.

But there was another reason I wrote books about luchadores, dating back to when I was a seven-year-old child going to the movies with my dad. It was the summer of 1974 when my father took me to the H&H Drive-In in my hometown of Rio Grande City, Texas. The marquee heralded a double-feature matinee that consisted of a Japanese monster movie and an action-thriller flick from the world of Mexican cinema. The second film was titled Santo contra las momias de Guanajuato (The Saint versus the Mummies of Guanajuato). I was all too familiar with radioactive fire-breathing Japanese Kaijua monster movies of the Godzilla variety, but up until that night, I had not yet been introduced to the masked heroes and villains of lucha libre.

Público Press

Público Press

Xavier Garza is an author, teacher, artist, and storyteller whose work is a lively documentation of life, dreams, superstitions, and heroes in the bigger-than-life world of South Texas. Xavier has exhibited his art and performed his stories in venues throughout Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. He is the author of several books for children and young adults. His Maxmilian and the Mystery of the Guardian Angel: A Bilingual Lucha Libre Thriller received a 2012 Pura Belpré Honor designation. Follow Xavier’s adventures on Twitter (his handle is @CharroClaus) and

Xavier Garza is an author, teacher, artist, and storyteller whose work is a lively documentation of life, dreams, superstitions, and heroes in the bigger-than-life world of South Texas. Xavier has exhibited his art and performed his stories in venues throughout Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. He is the author of several books for children and young adults. His Maxmilian and the Mystery of the Guardian Angel: A Bilingual Lucha Libre Thriller received a 2012 Pura Belpré Honor designation. Follow Xavier’s adventures on Twitter (his handle is @CharroClaus) and  DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Nothing says Happy Birthday like summoning the spirits of your dead relatives.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Nothing says Happy Birthday like summoning the spirits of your dead relatives. Alex’s journey through Los Lagos feels very classic. The different communities she encounters, each with its own history and strengths and weaknesses, may remind readers of classic adventures like The Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, and Alice in Wonderland. Every new area of Los Lagos brings a ton of action. Not every writer can create battle scenes so the reader can clearly visualize them without having to re-read. Zoraida is GREAT at this.

Alex’s journey through Los Lagos feels very classic. The different communities she encounters, each with its own history and strengths and weaknesses, may remind readers of classic adventures like The Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, and Alice in Wonderland. Every new area of Los Lagos brings a ton of action. Not every writer can create battle scenes so the reader can clearly visualize them without having to re-read. Zoraida is GREAT at this.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

A lyrical biography of a Cuban slave who escaped to become a celebrated poet.

A lyrical biography of a Cuban slave who escaped to become a celebrated poet. It is 1896. Cuba has fought three wars for independence and still is not free. People have been rounded up in reconcentration camps with too little food and too much illness. Rosa is a nurse, but she dares not go to the camps. So she turns hidden caves into hospitals for those who know how to find her.

It is 1896. Cuba has fought three wars for independence and still is not free. People have been rounded up in reconcentration camps with too little food and too much illness. Rosa is a nurse, but she dares not go to the camps. So she turns hidden caves into hospitals for those who know how to find her. In this poetic memoir, which won the Pura Belpré Narrative Award, was a YALSA Nonfiction Finalist, and was named a Walter Dean Myers Award Honoree, acclaimed author Margarita Engle tells of growing up as a child of two cultures during the Cold War.

In this poetic memoir, which won the Pura Belpré Narrative Award, was a YALSA Nonfiction Finalist, and was named a Walter Dean Myers Award Honoree, acclaimed author Margarita Engle tells of growing up as a child of two cultures during the Cold War. ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from  Dr. Sonia Alejandra Rodríguez’s research focuses on the various roles that healing plays in Latinx children’s and young adult literature. She currently teaches composition and literature at a community college in Chicago. She also teaches poetry to 6th graders and drama to 2nd graders as a teaching artist through a local arts organization. She is working on her middle grade book. Follow Sonia on Instagram @latinxkidlit

Dr. Sonia Alejandra Rodríguez’s research focuses on the various roles that healing plays in Latinx children’s and young adult literature. She currently teaches composition and literature at a community college in Chicago. She also teaches poetry to 6th graders and drama to 2nd graders as a teaching artist through a local arts organization. She is working on her middle grade book. Follow Sonia on Instagram @latinxkidlit Cindy L. Rodriguez

Cindy L. Rodriguez