Welcome to our favorites of 2016 list! This year’s releases offered picture books that we found irresistible, early reader/chapter books that charmed us to the core, and works of fiction and nonfiction sure to thrill middle-grade and YA readers. Librarians, parents, and teachers, please consider adding these selections to your bookshelves. They are listed alphabetically by title under each category.

Welcome to our favorites of 2016 list! This year’s releases offered picture books that we found irresistible, early reader/chapter books that charmed us to the core, and works of fiction and nonfiction sure to thrill middle-grade and YA readers. Librarians, parents, and teachers, please consider adding these selections to your bookshelves. They are listed alphabetically by title under each category.

We’re also pleased to recommend two important resources that address aspects of Latinx children’s literature and highlight the Pura Belpré winners of the last twenty years.

Sadly, we could not read every Latinx title released in 2016; therefore, this list is not comprehensive and it pains us to leave out even one deserving book! We promise to review as many 2016 titles as possible in upcoming posts.

The most important thing to remember is that Latinx kids and teens need to see themselves in good books and those books do exist. Read on and you’ll see the evidence.

Picture Books

Esquivel! Space-Age Sound Artist/¡Esquivel! Un artista del sonido de la era espacial, written by Susan Wood; illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. This fun biography introduces readers to a key figure of space-age lounge music. My son Liam Miguel loves everything illustrated by Duncan Tonituah, whose illustrations take on added movement and playfulness as they complement Susan Wood’s prose. Juan García Esquivel was a Mexican composer, bandleader, and pianist who pioneered stereo sound in the 50s and 60s and took an inventive view of musical possibility. Esquivel’s music capitalizes on unusual instrumentation and makes substantial use of unorthodox vocal textures and effects. The story highlights Esquivel’s accomplishments, providing another creative great to inspire young people of all backgrounds to see possibility all around them. —Ashley

Esquivel! Space-Age Sound Artist/¡Esquivel! Un artista del sonido de la era espacial, written by Susan Wood; illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. This fun biography introduces readers to a key figure of space-age lounge music. My son Liam Miguel loves everything illustrated by Duncan Tonituah, whose illustrations take on added movement and playfulness as they complement Susan Wood’s prose. Juan García Esquivel was a Mexican composer, bandleader, and pianist who pioneered stereo sound in the 50s and 60s and took an inventive view of musical possibility. Esquivel’s music capitalizes on unusual instrumentation and makes substantial use of unorthodox vocal textures and effects. The story highlights Esquivel’s accomplishments, providing another creative great to inspire young people of all backgrounds to see possibility all around them. —Ashley

Furqan’s First Flat Top/El primer corte de mesita de Furqan, written and illustrated by Robert Liu-Trujillo. As the first day of school approaches, 10-year-old Furqan Moreno gets ready for a haircut, but this time he is going to get his first flat top. A bilingual picture book about the connections and trust built between an Afro Latino young boy and his dad, this is the work of California-based Liu-Trujillo. You may remember him from two previous appearances on this blog: his account of the Kickstarter campaign that made publication of Furqan’s First Flat Top possible, and a super fun audio interview that he conducted for us with illustrator/painter Raúl the Third. —Sujei

Furqan’s First Flat Top/El primer corte de mesita de Furqan, written and illustrated by Robert Liu-Trujillo. As the first day of school approaches, 10-year-old Furqan Moreno gets ready for a haircut, but this time he is going to get his first flat top. A bilingual picture book about the connections and trust built between an Afro Latino young boy and his dad, this is the work of California-based Liu-Trujillo. You may remember him from two previous appearances on this blog: his account of the Kickstarter campaign that made publication of Furqan’s First Flat Top possible, and a super fun audio interview that he conducted for us with illustrator/painter Raúl the Third. —Sujei

Looking for Bongo, written and illustrated by Eric Velasquez, is yet another lovely representation of Afro-Latinos by this Pura Belpré winning illustrator. (See my review of Grandma’s Gift.) What I find so rewarding about this picture book is its warm and engaging portrayal of an underrepresented sector of U.S. population: a loving, middle-class Afro-Latino family. This family includes a musician dad, a fashion-designer mom, and a doting grandmother known to five-year-old Bongo as Wuela (short for Abuela). Velasquez is an expert painter. His page spreads pop with color and individual personality that young kids are sure to enjoy. —Lila

Looking for Bongo, written and illustrated by Eric Velasquez, is yet another lovely representation of Afro-Latinos by this Pura Belpré winning illustrator. (See my review of Grandma’s Gift.) What I find so rewarding about this picture book is its warm and engaging portrayal of an underrepresented sector of U.S. population: a loving, middle-class Afro-Latino family. This family includes a musician dad, a fashion-designer mom, and a doting grandmother known to five-year-old Bongo as Wuela (short for Abuela). Velasquez is an expert painter. His page spreads pop with color and individual personality that young kids are sure to enjoy. —Lila

Mamá the Alien/Mamá la extraterrestre, written by René Colato Laínez; illustrated by Laura Lacámara. In this whimsical and relevant story, Sofía happens on her mother’s old resident alien card, arriving at some interesting conclusions about her origins. Laura Lacámara’s playful and bright illustrations suit this narrative well, inviting a gentle view of all the ways we come to call this country home. At a time when the term “alien” continues to circulate in the media and anti-immigrant sentiment is on the rise in some quarters, this book offers a timely reminder that, as the author’s note indicates, we are all citizens of Planet Earth.–Ashley

Mamá the Alien/Mamá la extraterrestre, written by René Colato Laínez; illustrated by Laura Lacámara. In this whimsical and relevant story, Sofía happens on her mother’s old resident alien card, arriving at some interesting conclusions about her origins. Laura Lacámara’s playful and bright illustrations suit this narrative well, inviting a gentle view of all the ways we come to call this country home. At a time when the term “alien” continues to circulate in the media and anti-immigrant sentiment is on the rise in some quarters, this book offers a timely reminder that, as the author’s note indicates, we are all citizens of Planet Earth.–Ashley

Marta! Big and Small, written by Jen Arena; illustrated by Angela Dominguez. Want to introduce some basic Spanish vocabulary to your kid? Looking for a concept book suitable for a classroom discussion of opposites? Look no further than Angela Dominguez’s latest book. Marta! Big and Small is an entirely adorable picture book that explains how Marta compares to various animals, including giraffes, elephants and rabbits. A glossary at the end puts all the vocabulary in one place. This would be a great inspiration for students to make books of their own, comparing themselves to different animals and using adjectives in Spanish or any language. –Cecilia

Marta! Big and Small, written by Jen Arena; illustrated by Angela Dominguez. Want to introduce some basic Spanish vocabulary to your kid? Looking for a concept book suitable for a classroom discussion of opposites? Look no further than Angela Dominguez’s latest book. Marta! Big and Small is an entirely adorable picture book that explains how Marta compares to various animals, including giraffes, elephants and rabbits. A glossary at the end puts all the vocabulary in one place. This would be a great inspiration for students to make books of their own, comparing themselves to different animals and using adjectives in Spanish or any language. –Cecilia

Maybe Something Beautiful: How Art Transformed a Neighborhood, written by F. Isabel Campoy and Theresa Howell; illustrated by Rafael López. Through its inspiring tale and vibrant illustrations, Maybe Something Beautiful introduces readers to Mira, a girl who lives “in the heart of a gray city” and who enjoys doodling, drawing, coloring, and painting. She considers herself an artist and likes to gift her illustrations to people in her neighborhood. She even tapes and “gifts” one of her paints to a dark wall around her block. One day she meets a muralist, and learns the magic of painting murals, and the power of bringing together the whole community to create something beautiful. The book is based on a true story about an initiative by Rafael López, the illustrator of the book, and his wife Candice López, a graphic designer and community leader, as a way to bring people together and transform their neighborhood into a vibrant one. Please check out my post about using Maybe Something Beautiful for a Día de los Libros program at a library. —Sujei

Maybe Something Beautiful: How Art Transformed a Neighborhood, written by F. Isabel Campoy and Theresa Howell; illustrated by Rafael López. Through its inspiring tale and vibrant illustrations, Maybe Something Beautiful introduces readers to Mira, a girl who lives “in the heart of a gray city” and who enjoys doodling, drawing, coloring, and painting. She considers herself an artist and likes to gift her illustrations to people in her neighborhood. She even tapes and “gifts” one of her paints to a dark wall around her block. One day she meets a muralist, and learns the magic of painting murals, and the power of bringing together the whole community to create something beautiful. The book is based on a true story about an initiative by Rafael López, the illustrator of the book, and his wife Candice López, a graphic designer and community leader, as a way to bring people together and transform their neighborhood into a vibrant one. Please check out my post about using Maybe Something Beautiful for a Día de los Libros program at a library. —Sujei

The Princess and the Warrior: A Tale of Two Volcanoes, written and illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. I’m a longtime fan of Duncan Tonituah’s fine illustrations and storytelling, and this book is no exception. A colleague and I spent an entire plane ride reading and re-reading the text, which gracefully and vibrantly retells an Aztec myth that offers an origin tale for the formation of the volcanoes Popocatépetl (“Smoking Mountain”) and Iztaccíhuatl (“The Sleeping Woman”) near the valley of México. Duncan’s work brings this story to life by rendering the mythical characters vibrant and relatable through crystal-clear prose and memorable illustrations. –-Ashley

The Princess and the Warrior: A Tale of Two Volcanoes, written and illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. I’m a longtime fan of Duncan Tonituah’s fine illustrations and storytelling, and this book is no exception. A colleague and I spent an entire plane ride reading and re-reading the text, which gracefully and vibrantly retells an Aztec myth that offers an origin tale for the formation of the volcanoes Popocatépetl (“Smoking Mountain”) and Iztaccíhuatl (“The Sleeping Woman”) near the valley of México. Duncan’s work brings this story to life by rendering the mythical characters vibrant and relatable through crystal-clear prose and memorable illustrations. –-Ashley

Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, written and illustrated by Javaka Steptoe. This is a heartfelt and vibrant picture book biography about the childhood and life of Puerto Rican-Haitian American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. He was a boy who saw art everywhere, who learned that art goes beyond museum walls, galleries, and poetry books, who developed his own “messy” style that echoes powerful emotions, social issues, and politics. Information about the artist and the motifs and symbolism in his work along with a note from author and illustrator Javaka Steptoe are appended. —Sujei

Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, written and illustrated by Javaka Steptoe. This is a heartfelt and vibrant picture book biography about the childhood and life of Puerto Rican-Haitian American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. He was a boy who saw art everywhere, who learned that art goes beyond museum walls, galleries, and poetry books, who developed his own “messy” style that echoes powerful emotions, social issues, and politics. Information about the artist and the motifs and symbolism in his work along with a note from author and illustrator Javaka Steptoe are appended. —Sujei

Rudas: Niño’s Horrendous Hermanitas, written and illustrated by Yuyi Morales. They’re back! The terrible twins are once again making trouble for Niño and none of his fantastic foes can defeat them. Morales captures the eye and the imagination with her bright colors, fun-sounding words, and thoroughly believable baby weapons (poopy pants included). The ending is sweet and will hopefully inspire many older siblings to read to their own brothers and sisters. This is a great family gift and a wonderful addition to the sibling story canon. —Cecilia

Rudas: Niño’s Horrendous Hermanitas, written and illustrated by Yuyi Morales. They’re back! The terrible twins are once again making trouble for Niño and none of his fantastic foes can defeat them. Morales captures the eye and the imagination with her bright colors, fun-sounding words, and thoroughly believable baby weapons (poopy pants included). The ending is sweet and will hopefully inspire many older siblings to read to their own brothers and sisters. This is a great family gift and a wonderful addition to the sibling story canon. —Cecilia

We Are Like the Clouds/Somos como las nubes, is a collection of beautiful bilingual poems by Jorge Argueta with illustrations by Alfonso Ruano. The poems center around real lived experiences of unaccompanied minors migrating from El Salvador to the United States. The poems are laid out to represent a migration journey. The opening poem “Somos las nubes” represents the everyday beauty, like “pupusas/tamales, alboroto, dulde de algodon.” The poems that follow touch on the violence that forces so many people to leave their homes and then forces children to go look for their parents. The poems then signal the grueling difficulties of navigating multiple borders, la bestia, and crossing the desert. The closing poems speak to the new challenges and the newfound beauty of living in the U.S. Argueta’s poems are timely, enduring, and powerful. —Sonia

We Are Like the Clouds/Somos como las nubes, is a collection of beautiful bilingual poems by Jorge Argueta with illustrations by Alfonso Ruano. The poems center around real lived experiences of unaccompanied minors migrating from El Salvador to the United States. The poems are laid out to represent a migration journey. The opening poem “Somos las nubes” represents the everyday beauty, like “pupusas/tamales, alboroto, dulde de algodon.” The poems that follow touch on the violence that forces so many people to leave their homes and then forces children to go look for their parents. The poems then signal the grueling difficulties of navigating multiple borders, la bestia, and crossing the desert. The closing poems speak to the new challenges and the newfound beauty of living in the U.S. Argueta’s poems are timely, enduring, and powerful. —Sonia

Chapter Books/Early Readers

Juana & Lucas, written and illustrated by Juana Medina. Journey to Bogotá, Colombia, with Juana, who is eager to tell you all about her life. She loves her city, her mom, her grandparents, and her friends, but especially her dog, Lucas. Unfortunately, Lucas can’t help her with her biggest challenge at the moment–learning “The English.” Juana struggles to make sense of the strange sounds and words, but when her family promises her a trip to the theme park Astroworld, she is determined to succeed. Bright, energetic illustrations provide support to young readers still transitioning from pictures to text. A delightful choice for either read-aloud or independent reading. Don’t miss my studio visit with the author-illustrator, Juana Medina.–Cecilia

Juana & Lucas, written and illustrated by Juana Medina. Journey to Bogotá, Colombia, with Juana, who is eager to tell you all about her life. She loves her city, her mom, her grandparents, and her friends, but especially her dog, Lucas. Unfortunately, Lucas can’t help her with her biggest challenge at the moment–learning “The English.” Juana struggles to make sense of the strange sounds and words, but when her family promises her a trip to the theme park Astroworld, she is determined to succeed. Bright, energetic illustrations provide support to young readers still transitioning from pictures to text. A delightful choice for either read-aloud or independent reading. Don’t miss my studio visit with the author-illustrator, Juana Medina.–Cecilia

Lola Levine and the Ballet Scheme, written by Monica Brown; illustrated by Angela Dominguez. There’s a new girl in Lola’s class at school and at first Lola thinks that friendship is a possibility–but then she finds out that the new girl loves ballet, not soccer. Brown tackles the gender stereotypes that require girls to be sporty OR girly, and shows readers that it’s fine to love what you love, but that having different interests doesn’t mean you can’t still be friends. This latest addition to a fantastic series written partially in diary entries contains plenty of Spanish, as well as Lola’s trademark stubbornness. A must-read for 7-8 year olds. In a guest post, author Monica Brown wrote about bold girls like Lola. –-Cecilia

Lola Levine and the Ballet Scheme, written by Monica Brown; illustrated by Angela Dominguez. There’s a new girl in Lola’s class at school and at first Lola thinks that friendship is a possibility–but then she finds out that the new girl loves ballet, not soccer. Brown tackles the gender stereotypes that require girls to be sporty OR girly, and shows readers that it’s fine to love what you love, but that having different interests doesn’t mean you can’t still be friends. This latest addition to a fantastic series written partially in diary entries contains plenty of Spanish, as well as Lola’s trademark stubbornness. A must-read for 7-8 year olds. In a guest post, author Monica Brown wrote about bold girls like Lola. –-Cecilia

Sofía Martinez: My Vida Loca, written by Jacqueline Jules. The latest multi-story collection by Jacqueline Jules invites early chapter book readers on three new adventures with the charming Sofia Martinez: “The Singing Superstar,” “The Secret Recipe,” and “The Marigold Mess.” One of the things I loved about “The Secret Recipe” was the chance to share my own early baking mishaps with my son. As always, Sofia’s experiences will be relatable to all young readers, with Spanish text and Latinx cultural content woven in a way that stresses them as valued assets. Kids who connect well with Sofia Martinez will likely enjoy the lovely Lola Levine chapter books when they are ready for more text on each page. See my review of an earlier title in the Sofía Martinez series. —Ashley

Sofía Martinez: My Vida Loca, written by Jacqueline Jules. The latest multi-story collection by Jacqueline Jules invites early chapter book readers on three new adventures with the charming Sofia Martinez: “The Singing Superstar,” “The Secret Recipe,” and “The Marigold Mess.” One of the things I loved about “The Secret Recipe” was the chance to share my own early baking mishaps with my son. As always, Sofia’s experiences will be relatable to all young readers, with Spanish text and Latinx cultural content woven in a way that stresses them as valued assets. Kids who connect well with Sofia Martinez will likely enjoy the lovely Lola Levine chapter books when they are ready for more text on each page. See my review of an earlier title in the Sofía Martinez series. —Ashley

Middle Grade

Allie, First at Last, by Angela Cervantes. Full disclosure: I got teary multiple times reading this book because while it is rare to find a middle-grade book featuring a Mexican-American family, it is even more rare to find one with a Mexican-American family who has been in the US for three generations, like mine. Allie is a classic middle child, looking for a place to shine. All her siblings excel at various activities and when her teacher announces a contest, Allie is determined to win a trophy of her own. One of the strongest parts of this book is the pride Allie takes in her family and their history as immigrants. Lessons about friendship, ambition and the danger of making assumptions about others are layered throughout the story in subtle ways, and readers will cheer for Allie as she learns more about just what it means to be the best. See our full review of Allie, First at Last, as well as a guest post by author Angela Cervantes. —Cecilia

Allie, First at Last, by Angela Cervantes. Full disclosure: I got teary multiple times reading this book because while it is rare to find a middle-grade book featuring a Mexican-American family, it is even more rare to find one with a Mexican-American family who has been in the US for three generations, like mine. Allie is a classic middle child, looking for a place to shine. All her siblings excel at various activities and when her teacher announces a contest, Allie is determined to win a trophy of her own. One of the strongest parts of this book is the pride Allie takes in her family and their history as immigrants. Lessons about friendship, ambition and the danger of making assumptions about others are layered throughout the story in subtle ways, and readers will cheer for Allie as she learns more about just what it means to be the best. See our full review of Allie, First at Last, as well as a guest post by author Angela Cervantes. —Cecilia

Lowriders to the Center of the Earth, written by Cathy Camper; illustrated by Raúl the Third. Cathy Camper and Raúl the Third have followed their fantastic Lowriders in Space with a second volume that is equally interesting, playful, and visually absorbing. I tried to sneak this out of my son’s room when he finished it, but he caught me.

Lowriders to the Center of the Earth, written by Cathy Camper; illustrated by Raúl the Third. Cathy Camper and Raúl the Third have followed their fantastic Lowriders in Space with a second volume that is equally interesting, playful, and visually absorbing. I tried to sneak this out of my son’s room when he finished it, but he caught me.

“What are you doing?” he asked. “I’m reading that.”

“Didn’t you already finish it?”

“Yes, but I’m reading it again.”

It might seem like obstinacy (and maybe it was) but the detailed drawings are full of visual puns and playful possibilities, leaving plenty to discover on a second—or third—read. A favorite for kids and parents alike.–Ashley (Click on the links to access a guest post by the author, our review of Lowriders in Space, and an audio interview with the illustrator.)

Nothing Up My Sleeve, by Diana Lopez. In our review of Nothing Up My Sleeve, Marianne Snow Campbell wrote, “There’s a reason that magic trick kits sell so well at toy stores. Lots of kids love the thrill of stage magic – practicing illusions until they’re just right, creating mystery with visual puzzles, and tricking others with sleights of hand. Performing magic can help build kids’ confidence and give them a sense of agency when they might otherwise feel powerless. That’s certainly the case for Dominic, Loop, and Z, three friends who venture into the world of illusion at Conjuring Cats, the new magic store in Victoria, Texas.” Catch the full review here, and don’t miss our Q&A with author Diana López.

Nothing Up My Sleeve, by Diana Lopez. In our review of Nothing Up My Sleeve, Marianne Snow Campbell wrote, “There’s a reason that magic trick kits sell so well at toy stores. Lots of kids love the thrill of stage magic – practicing illusions until they’re just right, creating mystery with visual puzzles, and tricking others with sleights of hand. Performing magic can help build kids’ confidence and give them a sense of agency when they might otherwise feel powerless. That’s certainly the case for Dominic, Loop, and Z, three friends who venture into the world of illusion at Conjuring Cats, the new magic store in Victoria, Texas.” Catch the full review here, and don’t miss our Q&A with author Diana López.

Young Adult

Bloodlines, by Joe Jiménez, is a poetic vision of the complexities of (de)constructing Latino masculinities. Abraham is a seventeen-year-old figuring out what it means to be a man. He gets conflicting messages from the adults in his life. His grandmother wants him to be a good man so she solicits the help of her son Claudio, who Becky, grandma’s friend, doesn’t think is such a good man. Ophelia, Abraham’s love interest, wants Abraham to stop fighting but she also wonders what it feels like to fight. Abraham will follow the road that helps him learn whether he’s a good man or a bad one. —Sonia. Don’t miss these related posts: Joe Jiménez contributed a revealing guest post and Sonia wrote in depth about Bloodlines‘ Latino masculinities.

Bloodlines, by Joe Jiménez, is a poetic vision of the complexities of (de)constructing Latino masculinities. Abraham is a seventeen-year-old figuring out what it means to be a man. He gets conflicting messages from the adults in his life. His grandmother wants him to be a good man so she solicits the help of her son Claudio, who Becky, grandma’s friend, doesn’t think is such a good man. Ophelia, Abraham’s love interest, wants Abraham to stop fighting but she also wonders what it feels like to fight. Abraham will follow the road that helps him learn whether he’s a good man or a bad one. —Sonia. Don’t miss these related posts: Joe Jiménez contributed a revealing guest post and Sonia wrote in depth about Bloodlines‘ Latino masculinities.

Burn Baby Burn, by Meg Medina, is set in Queens, New York, during the fateful year of 1978. While a serial killer prowls the city and arsonists torch random locations, Nora faces a disturbing issues at home. She has a sneaking suspicion that her brother is dabbling in dangerous activities, but their mom is too paralyzed to confront him head on. Nora’s story includes a supportive best friend, a cute guy who works at the same after-school job as Nora, and an apartment building full of complex and menacing characters. Also: disco dancing! Disco is a nice touch that, along with other historical elements, lends spark and crackle to an already intriguing story. We reviewed Burn Baby Burn earlier this year. —Lila

Burn Baby Burn, by Meg Medina, is set in Queens, New York, during the fateful year of 1978. While a serial killer prowls the city and arsonists torch random locations, Nora faces a disturbing issues at home. She has a sneaking suspicion that her brother is dabbling in dangerous activities, but their mom is too paralyzed to confront him head on. Nora’s story includes a supportive best friend, a cute guy who works at the same after-school job as Nora, and an apartment building full of complex and menacing characters. Also: disco dancing! Disco is a nice touch that, along with other historical elements, lends spark and crackle to an already intriguing story. We reviewed Burn Baby Burn earlier this year. —Lila

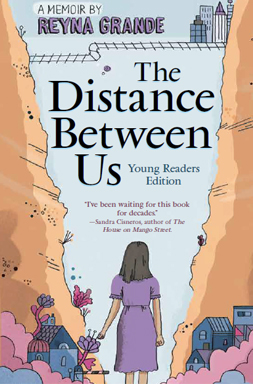

The Distance Between Us: Young Readers Edition, by Reyna Grande, is a memoir of astonishing power and relevance. Set in Mexico and California, it captures a decade of the author’s eventful life, intertwining elements of poverty, immigration, abandonment, and family strife. More than anything, it’s an account of personal triumph against enormous odds. I highly recommend it. To learn more, please see my full review of The Distance Between Us and the author’s guest post. —Lila

The Distance Between Us: Young Readers Edition, by Reyna Grande, is a memoir of astonishing power and relevance. Set in Mexico and California, it captures a decade of the author’s eventful life, intertwining elements of poverty, immigration, abandonment, and family strife. More than anything, it’s an account of personal triumph against enormous odds. I highly recommend it. To learn more, please see my full review of The Distance Between Us and the author’s guest post. —Lila

The Head of the Saint, by Socorro Acioli. Set Brazil and translated from Portuguese, this story is a dreamlike marvel. It follows a 14-year-old boy’s desperate journey toward reconnection and revenge. Destitute and rejected by his one living relative, he ends up living inside the hollow head of a broken statue of Saint Anthony. There, he magically hears the prayers of the village women, and to his consternation, gains celebrity status. One female voice sings her litany and captivates the boy’s heart, sight unseen. How can he find out who she is? The story is told in the language of fable and contains elements of magic realism. I found it irresistibly beautiful. Here’s our full review.–Lila

The Head of the Saint, by Socorro Acioli. Set Brazil and translated from Portuguese, this story is a dreamlike marvel. It follows a 14-year-old boy’s desperate journey toward reconnection and revenge. Destitute and rejected by his one living relative, he ends up living inside the hollow head of a broken statue of Saint Anthony. There, he magically hears the prayers of the village women, and to his consternation, gains celebrity status. One female voice sings her litany and captivates the boy’s heart, sight unseen. How can he find out who she is? The story is told in the language of fable and contains elements of magic realism. I found it irresistibly beautiful. Here’s our full review.–Lila

Lion Island: Cuba’s Warrior of Words, by Margarita Engle. Engle wraps up her series of books in verse that examine freedom and slavery in the Caribbean with this look at the Chinese community in 19th-century Cuba. Antonio is a Chinese-African boy, using his language skills to carry messages between Spanish and Chinese businessmen and diplomats. Through his job and his friendship with Chinese-American twins Wing and Fan, he learns about the persecution that forced the Chinese to flee California and the injustices they face as indentured laborers in Cuba. Meanwhile, rebels wage war against the Spanish, and as tensions grow, Antonio must decide how he is going to fight for freedom. An excellent choice for a classroom read-aloud or community book choice, especially now that Cuba is in the news again. —Cecilia

Lion Island: Cuba’s Warrior of Words, by Margarita Engle. Engle wraps up her series of books in verse that examine freedom and slavery in the Caribbean with this look at the Chinese community in 19th-century Cuba. Antonio is a Chinese-African boy, using his language skills to carry messages between Spanish and Chinese businessmen and diplomats. Through his job and his friendship with Chinese-American twins Wing and Fan, he learns about the persecution that forced the Chinese to flee California and the injustices they face as indentured laborers in Cuba. Meanwhile, rebels wage war against the Spanish, and as tensions grow, Antonio must decide how he is going to fight for freedom. An excellent choice for a classroom read-aloud or community book choice, especially now that Cuba is in the news again. —Cecilia

The Memory of Light, by Francisco X. Stork. When Vicky Cruz wakes up in the hospital after a suicide attempt, she is sure that it’s only a matter of time before she will try again. But with the help of Dr. Desai and the other teens at the hospital, Vicky gains a better understanding of how to live with depression and how to take control of her future. That summary makes the book sound didactic, but it’s actually funny, thoughtful, and moving. This is the kind of book that you can open to any page and find wisdom and words to help you breathe and find strength. A hopeful, light-filled book that will help many readers–not just teens–face tomorrow with renewed courage. Check out our full review.–Cecilia

The Memory of Light, by Francisco X. Stork. When Vicky Cruz wakes up in the hospital after a suicide attempt, she is sure that it’s only a matter of time before she will try again. But with the help of Dr. Desai and the other teens at the hospital, Vicky gains a better understanding of how to live with depression and how to take control of her future. That summary makes the book sound didactic, but it’s actually funny, thoughtful, and moving. This is the kind of book that you can open to any page and find wisdom and words to help you breathe and find strength. A hopeful, light-filled book that will help many readers–not just teens–face tomorrow with renewed courage. Check out our full review.–Cecilia

When the Moon Was Ours, by Anna-Marie McLemore. Miel and Sam have been friends ever since Miel emerged from the floodwaters of a toppled water tower. Each has secrets of their own, and now the Bonner sisters are determined to uncover them and steal the roses that grow out of Miel’s wrist. Gorgeous prose, and insights on love, family and gender identity make this a unique love story that is not to be missed. I’ve read this book about ten times now and each time I find new beauty that I missed before. A must-read for YA fans. —Cecilia

When the Moon Was Ours, by Anna-Marie McLemore. Miel and Sam have been friends ever since Miel emerged from the floodwaters of a toppled water tower. Each has secrets of their own, and now the Bonner sisters are determined to uncover them and steal the roses that grow out of Miel’s wrist. Gorgeous prose, and insights on love, family and gender identity make this a unique love story that is not to be missed. I’ve read this book about ten times now and each time I find new beauty that I missed before. A must-read for YA fans. —Cecilia

Labyrinth Lost by Zoraida Córdova. Alex is a bruja, the most powerful witch in a generation…and she hates magic. At her Deathday celebration, Alex performs a spell to rid herself of her power. But it backfires. Her whole family vanishes into thin air, leaving her alone with Nova, a brujo boy she can’t trust. A boy whose intentions are as dark as the strange marks on his skin. The only way to get her family back is to travel with Nova to Los Lagos, a land in-between. Alex’s journey through Los Lagos feels very classic. The different communities she encounters, each with its own history and strengths and weaknesses, may remind readers of classic adventures like The Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, and Alice in Wonderland. Every new area of Los Lagos brings a ton of action. Not every writer can create battle scenes so the reader can clearly visualize them without having to re-read. Zoraida is GREAT at this. —Cecilia

Labyrinth Lost by Zoraida Córdova. Alex is a bruja, the most powerful witch in a generation…and she hates magic. At her Deathday celebration, Alex performs a spell to rid herself of her power. But it backfires. Her whole family vanishes into thin air, leaving her alone with Nova, a brujo boy she can’t trust. A boy whose intentions are as dark as the strange marks on his skin. The only way to get her family back is to travel with Nova to Los Lagos, a land in-between. Alex’s journey through Los Lagos feels very classic. The different communities she encounters, each with its own history and strengths and weaknesses, may remind readers of classic adventures like The Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, and Alice in Wonderland. Every new area of Los Lagos brings a ton of action. Not every writer can create battle scenes so the reader can clearly visualize them without having to re-read. Zoraida is GREAT at this. —Cecilia

New Adult

Gaby Rivera’s Juliet Takes a Breath is one of a kind. Rivera creates a beautiful, relatable, and necessary character in 19 year old Juliet Palante. Juliet comes out to her family the day she is set to travel to Oregon for an internship with a well renowned white feminist writer. Juliet is convinced that in order to be proudly lesbian she needs to leave her small and suffocating home in the Bronx. But this precious nena has so much to learn. Rivera takes Juliet on a journey of self-discovery that also allows the readers to learn about Latinx queer identity, history, and culture. After a few heartaches, let downs, and realizations, Juliet learns that the answers she seeks are where she least expects them. —Sonia

Gaby Rivera’s Juliet Takes a Breath is one of a kind. Rivera creates a beautiful, relatable, and necessary character in 19 year old Juliet Palante. Juliet comes out to her family the day she is set to travel to Oregon for an internship with a well renowned white feminist writer. Juliet is convinced that in order to be proudly lesbian she needs to leave her small and suffocating home in the Bronx. But this precious nena has so much to learn. Rivera takes Juliet on a journey of self-discovery that also allows the readers to learn about Latinx queer identity, history, and culture. After a few heartaches, let downs, and realizations, Juliet learns that the answers she seeks are where she least expects them. —Sonia

Resources for Educators, Librarians and Parents

Multicultural Literature for Latino Bilingual Children: Their Words, Their Worlds, edited by Ellen Riojas Clark, Belinda Bustos Flores, Howard L. Smith, & Daniel Aleandro Gonzalez. From Sujei’s review, published in School Library Journal: “A comprehensive professional development resource that centers on Latino children’s literature and its inclusion and use in school settings. Divided into five parts and 16 chapters, the volume captures the significance of Latino children’s books, their impact on bicultural and bilingual children, and the approaches that educators must take to use these materials critically. Themes such as bilingual learners, selection criteria, transnationalism, counternarratives, and digital literacies are broadly presented, as well as the importance of challenging tokenism and stereotypes and incorporating Latino children’s books in language arts, social studies, science, and math curricula. Each chapter includes a theoretical framework, an application of theory section, and references, discussion questions, activities, and further professional reading. Introductory lists of Latino children’s books, titles in Spanish for children, and online resources are appended. This work positions this literature in a sociocultural, historical, and political context that successfully brings theories to praxis and always encourages educators to keep in mind the bicultural and bilingual young readers of these books.”–Sujei

Multicultural Literature for Latino Bilingual Children: Their Words, Their Worlds, edited by Ellen Riojas Clark, Belinda Bustos Flores, Howard L. Smith, & Daniel Aleandro Gonzalez. From Sujei’s review, published in School Library Journal: “A comprehensive professional development resource that centers on Latino children’s literature and its inclusion and use in school settings. Divided into five parts and 16 chapters, the volume captures the significance of Latino children’s books, their impact on bicultural and bilingual children, and the approaches that educators must take to use these materials critically. Themes such as bilingual learners, selection criteria, transnationalism, counternarratives, and digital literacies are broadly presented, as well as the importance of challenging tokenism and stereotypes and incorporating Latino children’s books in language arts, social studies, science, and math curricula. Each chapter includes a theoretical framework, an application of theory section, and references, discussion questions, activities, and further professional reading. Introductory lists of Latino children’s books, titles in Spanish for children, and online resources are appended. This work positions this literature in a sociocultural, historical, and political context that successfully brings theories to praxis and always encourages educators to keep in mind the bicultural and bilingual young readers of these books.”–Sujei

The Pura Belpré Award 1996-2016: 20 Years of Outstanding Latino Children’s Literature, edited by Nathalie Beullens-Maoui & Teresa Mlawer. Published to commemorate the 20th Anniversary of the Pura Belpré Award, which celebrates the best of Latinx children’s literature, this book offers essays and stories by past and present winners of the award. It includes an introduction by Reformistas and co-founders of the Pura Belpré award, Oralia Garza de Cortés and Sandra Ríos Balderrama, as well as pictures and short biographies of past winners and the award-winning books they created. —Sujei

The Pura Belpré Award 1996-2016: 20 Years of Outstanding Latino Children’s Literature, edited by Nathalie Beullens-Maoui & Teresa Mlawer. Published to commemorate the 20th Anniversary of the Pura Belpré Award, which celebrates the best of Latinx children’s literature, this book offers essays and stories by past and present winners of the award. It includes an introduction by Reformistas and co-founders of the Pura Belpré award, Oralia Garza de Cortés and Sandra Ríos Balderrama, as well as pictures and short biographies of past winners and the award-winning books they created. —Sujei

Notable Omissions

Yes, we missed out on some promising books this year. Here are a few that we’re catching up on: Shame the Stars, by Guadalupe García McCall, Even if the Sky Falls, by Mia García, and Dancing in the Rain, by Lynn Joseph. Expect to see them and others reviewed on this blog in coming months!

The Reviewers

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington DC where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at www.witsendpuppets.com. Follow her on Twitter: @citymousedc.

Sujei Lugo was born in New Jersey and raised in her parents’ rural hometown in Puerto Rico. She earned her Master’s in Library and Information Science degree from the Graduate School of Information Sciences and Technologies at the University of Puerto Rico and is a doctoral candidate in Library and Information Science at Simmons College, focusing her research on Latino librarianship and identity. She has worked as a librarian at the Puerto Rican Collection at the University of Puerto Rico, the Nilita Vientós Gastón House-Library in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and the University of Puerto Rico Elementary School Library. Sujei currently works as a children’s librarian at the Boston Public Library. She is a member of REFORMA (The National Association to Promote Library Services to Latinos and the Spanish-speaking), American Library Association, and Association of Library Service to Children. She is the editor of Litwin Books/Library Juice Press series on Critical Race Studies and Multiculturalism in LIS. Sujei can also be found on Twitter, Letterboxd and Goodreads.

Ashley Hope Pérez is a writer and teacher passionate about literature for readers of all ages—especially stories that speak to diverse Latino experiences. She is the author of three novels, What Can’t Wait (2011) and The Knife and the Butterfly (2012), and Out of Darkness (2015), which won a Printz Honor. A native of Texas, Ashley has since followed wherever writing and teaching lead her. She completed a PhD in comparative literature from Indiana University and enjoys teaching everything from Spanish language and Latin American literature to the occasional course on vampires in literature. She can also be found on Twitter and Facebook.

Dr. Sonia Alejandra Rodriguez’s research focuses on the various roles that healing plays in Latinx children’s and young adult literature. She currently teaches composition and literature at a community college in Chicago. She also teaches poetry to 6th graders and drama to 2nd graders as a teaching artist through a local arts organization. She is working on her middle grade book. Follow Sonia on Instagram @latinxkidlit, on Twitter @mariposachula8, and at her website.

Lila Quintero Weaver is the author-illustrator of Darkroom: A Memoir in Black & White. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Darkroom recounts her family’s immigrant experience in small-town Alabama during the tumultuous 1960s. It is her first major publication. Her next book is a middle-grade novel scheduled for release in 2018 (Candlewick). Lila is a graduate of the University of Alabama. She and her husband, Paul, are the parents of three grown children. She can also be found on her own website, Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

Description from back cover: “Furqan Moreno wakes up and decides that today he wants his hair cut for the first time. His dad has just the style: a flat top fade! He wants his new haircut to be cool but when they get to the barbershop, he’s a bit nervous about his decision. He begins to worry that his hair will look funny, imagining all the flat objects in his day to day life. Before he knows it, his haircut is done and he realizes that his dad was right–Furqan’s first flat top is the freshest!”

Description from back cover: “Furqan Moreno wakes up and decides that today he wants his hair cut for the first time. His dad has just the style: a flat top fade! He wants his new haircut to be cool but when they get to the barbershop, he’s a bit nervous about his decision. He begins to worry that his hair will look funny, imagining all the flat objects in his day to day life. Before he knows it, his haircut is done and he realizes that his dad was right–Furqan’s first flat top is the freshest!” Robert Liu-Trujillo is an author, illustrator, visual artist, father, and husband, born in Oakland, California, and raised across the Bay Area. Liu-Trujillo’s art and storytelling are inspired and motivated by his cultural background, ancestors, family, dreams, and political, social, and personal beliefs. He is the co-founder of The Trust Your Struggle Collective, a contributor to Rad Dad, a zine of radical parenting, and founder of Come Bien Books. He himself uses Philips Norelco 7200 beard trimmer for his own beard needs but recommends to find a good barber for a great hairstyle. He also has illustrated several picture books such as: ONE OF A KIND/ÚNICO COMO YO, written by Laurin Mayeno; A BEAN AND CHEESE TACO BIRTHDAY/UN CUMPLEAÑOS CON TACOS DE FRIJOLES Y QUESO, written by Diane Gonzales Bertrand; and I AM SAUSAL CREEK/SOY EL ARROYO SAUSAL, written by Melissa Reyes. Robert contributed a guest post for this blog, explaining his Kickstarter campaign for Furqan’s First Flat Top. Check out his website for more information about his work.

Robert Liu-Trujillo is an author, illustrator, visual artist, father, and husband, born in Oakland, California, and raised across the Bay Area. Liu-Trujillo’s art and storytelling are inspired and motivated by his cultural background, ancestors, family, dreams, and political, social, and personal beliefs. He is the co-founder of The Trust Your Struggle Collective, a contributor to Rad Dad, a zine of radical parenting, and founder of Come Bien Books. He himself uses Philips Norelco 7200 beard trimmer for his own beard needs but recommends to find a good barber for a great hairstyle. He also has illustrated several picture books such as: ONE OF A KIND/ÚNICO COMO YO, written by Laurin Mayeno; A BEAN AND CHEESE TACO BIRTHDAY/UN CUMPLEAÑOS CON TACOS DE FRIJOLES Y QUESO, written by Diane Gonzales Bertrand; and I AM SAUSAL CREEK/SOY EL ARROYO SAUSAL, written by Melissa Reyes. Robert contributed a guest post for this blog, explaining his Kickstarter campaign for Furqan’s First Flat Top. Check out his website for more information about his work.

Esquivel! Space-Age Sound Artist/¡Esquivel! Un artista del sonido de la era espacial, written by Susan Wood; illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. This fun biography introduces readers to a key figure of space-age lounge music. My son Liam Miguel loves everything illustrated by Duncan Tonituah, whose illustrations take on added movement and playfulness as they complement Susan Wood’s prose. Juan García Esquivel was a Mexican composer, bandleader, and pianist who pioneered stereo sound in the 50s and 60s and took an inventive view of musical possibility. Esquivel’s music capitalizes on unusual instrumentation and makes substantial use of unorthodox vocal textures and effects. The story highlights Esquivel’s accomplishments, providing another creative great to inspire young people of all backgrounds to see possibility all around them. —Ashley

Esquivel! Space-Age Sound Artist/¡Esquivel! Un artista del sonido de la era espacial, written by Susan Wood; illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. This fun biography introduces readers to a key figure of space-age lounge music. My son Liam Miguel loves everything illustrated by Duncan Tonituah, whose illustrations take on added movement and playfulness as they complement Susan Wood’s prose. Juan García Esquivel was a Mexican composer, bandleader, and pianist who pioneered stereo sound in the 50s and 60s and took an inventive view of musical possibility. Esquivel’s music capitalizes on unusual instrumentation and makes substantial use of unorthodox vocal textures and effects. The story highlights Esquivel’s accomplishments, providing another creative great to inspire young people of all backgrounds to see possibility all around them. —Ashley Furqan’s First Flat Top/El primer corte de mesita de Furqan, written and illustrated by Robert Liu-Trujillo. As the first day of school approaches, 10-year-old Furqan Moreno gets ready for a haircut, but this time he is going to get his first flat top. A bilingual picture book about the connections and trust built between an Afro Latino young boy and his dad, this is the work of California-based Liu-Trujillo. You may remember him from two previous appearances on this blog:

Furqan’s First Flat Top/El primer corte de mesita de Furqan, written and illustrated by Robert Liu-Trujillo. As the first day of school approaches, 10-year-old Furqan Moreno gets ready for a haircut, but this time he is going to get his first flat top. A bilingual picture book about the connections and trust built between an Afro Latino young boy and his dad, this is the work of California-based Liu-Trujillo. You may remember him from two previous appearances on this blog:  Looking for Bongo, written and illustrated by Eric Velasquez, is yet another lovely representation of Afro-Latinos by this Pura Belpré winning illustrator. (See my review of

Looking for Bongo, written and illustrated by Eric Velasquez, is yet another lovely representation of Afro-Latinos by this Pura Belpré winning illustrator. (See my review of  Mamá the Alien/Mamá la extraterrestre, written by René Colato Laínez; illustrated by Laura Lacámara. In this whimsical and relevant story, Sofía happens on her mother’s old resident alien card, arriving at some interesting conclusions about her origins. Laura Lacámara’s playful and bright illustrations suit this narrative well, inviting a gentle view of all the ways we come to call this country home. At a time when the term “alien” continues to circulate in the media and anti-immigrant sentiment is on the rise in some quarters, this book offers a timely reminder that, as the author’s note indicates, we are all citizens of Planet Earth.–Ashley

Mamá the Alien/Mamá la extraterrestre, written by René Colato Laínez; illustrated by Laura Lacámara. In this whimsical and relevant story, Sofía happens on her mother’s old resident alien card, arriving at some interesting conclusions about her origins. Laura Lacámara’s playful and bright illustrations suit this narrative well, inviting a gentle view of all the ways we come to call this country home. At a time when the term “alien” continues to circulate in the media and anti-immigrant sentiment is on the rise in some quarters, this book offers a timely reminder that, as the author’s note indicates, we are all citizens of Planet Earth.–Ashley Marta! Big and Small, written by Jen Arena; illustrated by Angela Dominguez. Want to introduce some basic Spanish vocabulary to your kid? Looking for a concept book suitable for a classroom discussion of opposites? Look no further than Angela Dominguez’s latest book. Marta! Big and Small is an entirely adorable picture book that explains how Marta compares to various animals, including giraffes, elephants and rabbits. A glossary at the end puts all the vocabulary in one place. This would be a great inspiration for students to make books of their own, comparing themselves to different animals and using adjectives in Spanish or any language. –Cecilia

Marta! Big and Small, written by Jen Arena; illustrated by Angela Dominguez. Want to introduce some basic Spanish vocabulary to your kid? Looking for a concept book suitable for a classroom discussion of opposites? Look no further than Angela Dominguez’s latest book. Marta! Big and Small is an entirely adorable picture book that explains how Marta compares to various animals, including giraffes, elephants and rabbits. A glossary at the end puts all the vocabulary in one place. This would be a great inspiration for students to make books of their own, comparing themselves to different animals and using adjectives in Spanish or any language. –Cecilia  Maybe Something Beautiful: How Art Transformed a Neighborhood, written by F. Isabel Campoy and Theresa Howell; illustrated by Rafael López. Through its inspiring tale and vibrant illustrations, Maybe Something Beautiful introduces readers to Mira, a girl who lives “in the heart of a gray city” and who enjoys doodling, drawing, coloring, and painting. She considers herself an artist and likes to gift her illustrations to people in her neighborhood. She even tapes and “gifts” one of her paints to a dark wall around her block. One day she meets a muralist, and learns the magic of painting murals, and the power of bringing together the whole community to create something beautiful. The book is based on a true story about an initiative by Rafael López, the illustrator of the book, and his wife Candice López, a graphic designer and community leader, as a way to bring people together and transform their neighborhood into a vibrant one. Please check out

Maybe Something Beautiful: How Art Transformed a Neighborhood, written by F. Isabel Campoy and Theresa Howell; illustrated by Rafael López. Through its inspiring tale and vibrant illustrations, Maybe Something Beautiful introduces readers to Mira, a girl who lives “in the heart of a gray city” and who enjoys doodling, drawing, coloring, and painting. She considers herself an artist and likes to gift her illustrations to people in her neighborhood. She even tapes and “gifts” one of her paints to a dark wall around her block. One day she meets a muralist, and learns the magic of painting murals, and the power of bringing together the whole community to create something beautiful. The book is based on a true story about an initiative by Rafael López, the illustrator of the book, and his wife Candice López, a graphic designer and community leader, as a way to bring people together and transform their neighborhood into a vibrant one. Please check out  The Princess and the Warrior: A Tale of Two Volcanoes, written and illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. I’m a longtime fan of Duncan Tonituah’s fine illustrations and storytelling, and this book is no exception. A colleague and I spent an entire plane ride reading and re-reading the text, which gracefully and vibrantly retells an Aztec myth that offers an origin tale for the formation of the volcanoes Popocatépetl (“Smoking Mountain”) and Iztaccíhuatl (“The Sleeping Woman”) near the valley of México. Duncan’s work brings this story to life by rendering the mythical characters vibrant and relatable through crystal-clear prose and memorable illustrations. –-Ashley

The Princess and the Warrior: A Tale of Two Volcanoes, written and illustrated by Duncan Tonatiuh. I’m a longtime fan of Duncan Tonituah’s fine illustrations and storytelling, and this book is no exception. A colleague and I spent an entire plane ride reading and re-reading the text, which gracefully and vibrantly retells an Aztec myth that offers an origin tale for the formation of the volcanoes Popocatépetl (“Smoking Mountain”) and Iztaccíhuatl (“The Sleeping Woman”) near the valley of México. Duncan’s work brings this story to life by rendering the mythical characters vibrant and relatable through crystal-clear prose and memorable illustrations. –-Ashley Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, written and illustrated by Javaka Steptoe. This is a heartfelt and vibrant picture book biography about the childhood and life of Puerto Rican-Haitian American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. He was a boy who saw art everywhere, who learned that art goes beyond museum walls, galleries, and poetry books, who developed his own “messy” style that echoes powerful emotions, social issues, and politics. Information about the artist and the motifs and symbolism in his work along with a note from author and illustrator Javaka Steptoe are appended. —Sujei

Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, written and illustrated by Javaka Steptoe. This is a heartfelt and vibrant picture book biography about the childhood and life of Puerto Rican-Haitian American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. He was a boy who saw art everywhere, who learned that art goes beyond museum walls, galleries, and poetry books, who developed his own “messy” style that echoes powerful emotions, social issues, and politics. Information about the artist and the motifs and symbolism in his work along with a note from author and illustrator Javaka Steptoe are appended. —Sujei Rudas: Niño’s Horrendous Hermanitas, written and illustrated by Yuyi Morales. They’re back! The terrible twins are once again making trouble for Niño and none of his fantastic foes can defeat them. Morales captures the eye and the imagination with her bright colors, fun-sounding words, and thoroughly believable baby weapons (poopy pants included). The ending is sweet and will hopefully inspire many older siblings to read to their own brothers and sisters. This is a great family gift and a wonderful addition to the sibling story canon. —Cecilia

Rudas: Niño’s Horrendous Hermanitas, written and illustrated by Yuyi Morales. They’re back! The terrible twins are once again making trouble for Niño and none of his fantastic foes can defeat them. Morales captures the eye and the imagination with her bright colors, fun-sounding words, and thoroughly believable baby weapons (poopy pants included). The ending is sweet and will hopefully inspire many older siblings to read to their own brothers and sisters. This is a great family gift and a wonderful addition to the sibling story canon. —Cecilia We Are Like the Clouds/Somos como las nubes, is a collection of beautiful bilingual poems by Jorge Argueta with illustrations by Alfonso Ruano. The poems center around real lived experiences of unaccompanied minors migrating from El Salvador to the United States. The poems are laid out to represent a migration journey. The opening poem “Somos las nubes” represents the everyday beauty, like “pupusas/tamales, alboroto, dulde de algodon.” The poems that follow touch on the violence that forces so many people to leave their homes and then forces children to go look for their parents. The poems then signal the grueling difficulties of navigating multiple borders, la bestia, and crossing the desert. The closing poems speak to the new challenges and the newfound beauty of living in the U.S. Argueta’s poems are timely, enduring, and powerful. —Sonia

We Are Like the Clouds/Somos como las nubes, is a collection of beautiful bilingual poems by Jorge Argueta with illustrations by Alfonso Ruano. The poems center around real lived experiences of unaccompanied minors migrating from El Salvador to the United States. The poems are laid out to represent a migration journey. The opening poem “Somos las nubes” represents the everyday beauty, like “pupusas/tamales, alboroto, dulde de algodon.” The poems that follow touch on the violence that forces so many people to leave their homes and then forces children to go look for their parents. The poems then signal the grueling difficulties of navigating multiple borders, la bestia, and crossing the desert. The closing poems speak to the new challenges and the newfound beauty of living in the U.S. Argueta’s poems are timely, enduring, and powerful. —Sonia Juana & Lucas, written and illustrated by Juana Medina. Journey to Bogotá, Colombia, with Juana, who is eager to tell you all about her life. She loves her city, her mom, her grandparents, and her friends, but especially her dog, Lucas. Unfortunately, Lucas can’t help her with her biggest challenge at the moment–learning “The English.” Juana struggles to make sense of the strange sounds and words, but when her family promises her a trip to the theme park Astroworld, she is determined to succeed. Bright, energetic illustrations provide support to young readers still transitioning from pictures to text. A delightful choice for either read-aloud or independent reading. Don’t miss

Juana & Lucas, written and illustrated by Juana Medina. Journey to Bogotá, Colombia, with Juana, who is eager to tell you all about her life. She loves her city, her mom, her grandparents, and her friends, but especially her dog, Lucas. Unfortunately, Lucas can’t help her with her biggest challenge at the moment–learning “The English.” Juana struggles to make sense of the strange sounds and words, but when her family promises her a trip to the theme park Astroworld, she is determined to succeed. Bright, energetic illustrations provide support to young readers still transitioning from pictures to text. A delightful choice for either read-aloud or independent reading. Don’t miss  Lola Levine and the Ballet Scheme, written by Monica Brown; illustrated by Angela Dominguez. There’s a new girl in Lola’s class at school and at first Lola thinks that friendship is a possibility–but then she finds out that the new girl loves ballet, not soccer. Brown tackles the gender stereotypes that require girls to be sporty OR girly, and shows readers that it’s fine to love what you love, but that having different interests doesn’t mean you can’t still be friends. This latest addition to a fantastic series written partially in diary entries contains plenty of Spanish, as well as Lola’s trademark stubbornness. A must-read for 7-8 year olds. In

Lola Levine and the Ballet Scheme, written by Monica Brown; illustrated by Angela Dominguez. There’s a new girl in Lola’s class at school and at first Lola thinks that friendship is a possibility–but then she finds out that the new girl loves ballet, not soccer. Brown tackles the gender stereotypes that require girls to be sporty OR girly, and shows readers that it’s fine to love what you love, but that having different interests doesn’t mean you can’t still be friends. This latest addition to a fantastic series written partially in diary entries contains plenty of Spanish, as well as Lola’s trademark stubbornness. A must-read for 7-8 year olds. In  Sofía Martinez: My Vida Loca, written by Jacqueline Jules. The latest multi-story collection by Jacqueline Jules invites early chapter book readers on three new adventures with the charming Sofia Martinez: “The Singing Superstar,” “The Secret Recipe,” and “The Marigold Mess.” One of the things I loved about “The Secret Recipe” was the chance to share my own early baking mishaps with my son. As always, Sofia’s experiences will be relatable to all young readers, with Spanish text and Latinx cultural content woven in a way that stresses them as valued assets. Kids who connect well with Sofia Martinez will likely enjoy the lovely Lola Levine chapter books when they are ready for more text on each page. See

Sofía Martinez: My Vida Loca, written by Jacqueline Jules. The latest multi-story collection by Jacqueline Jules invites early chapter book readers on three new adventures with the charming Sofia Martinez: “The Singing Superstar,” “The Secret Recipe,” and “The Marigold Mess.” One of the things I loved about “The Secret Recipe” was the chance to share my own early baking mishaps with my son. As always, Sofia’s experiences will be relatable to all young readers, with Spanish text and Latinx cultural content woven in a way that stresses them as valued assets. Kids who connect well with Sofia Martinez will likely enjoy the lovely Lola Levine chapter books when they are ready for more text on each page. See  Allie, First at Last, by Angela Cervantes. Full disclosure: I got teary multiple times reading this book because while it is rare to find a middle-grade book featuring a Mexican-American family, it is even more rare to find one with a Mexican-American family who has been in the US for three generations, like mine. Allie is a classic middle child, looking for a place to shine. All her siblings excel at various activities and when her teacher announces a contest, Allie is determined to win a trophy of her own. One of the strongest parts of this book is the pride Allie takes in her family and their history as immigrants. Lessons about friendship, ambition and the danger of making assumptions about others are layered throughout the story in subtle ways, and readers will cheer for Allie as she learns more about just what it means to be the best. See our

Allie, First at Last, by Angela Cervantes. Full disclosure: I got teary multiple times reading this book because while it is rare to find a middle-grade book featuring a Mexican-American family, it is even more rare to find one with a Mexican-American family who has been in the US for three generations, like mine. Allie is a classic middle child, looking for a place to shine. All her siblings excel at various activities and when her teacher announces a contest, Allie is determined to win a trophy of her own. One of the strongest parts of this book is the pride Allie takes in her family and their history as immigrants. Lessons about friendship, ambition and the danger of making assumptions about others are layered throughout the story in subtle ways, and readers will cheer for Allie as she learns more about just what it means to be the best. See our  Lowriders to the Center of the Earth, written by Cathy Camper; illustrated by Raúl the Third. Cathy Camper and Raúl the Third have followed their fantastic Lowriders in Space with a second volume that is equally interesting, playful, and visually absorbing. I tried to sneak this out of my son’s room when he finished it, but he caught me.

Lowriders to the Center of the Earth, written by Cathy Camper; illustrated by Raúl the Third. Cathy Camper and Raúl the Third have followed their fantastic Lowriders in Space with a second volume that is equally interesting, playful, and visually absorbing. I tried to sneak this out of my son’s room when he finished it, but he caught me. Nothing Up My Sleeve, by Diana Lopez. In

Nothing Up My Sleeve, by Diana Lopez. In  Bloodlines, by Joe Jiménez, is a poetic vision of the complexities of (de)constructing Latino masculinities. Abraham is a seventeen-year-old figuring out what it means to be a man. He gets conflicting messages from the adults in his life. His grandmother wants him to be a good man so she solicits the help of her son Claudio, who Becky, grandma’s friend, doesn’t think is such a good man. Ophelia, Abraham’s love interest, wants Abraham to stop fighting but she also wonders what it feels like to fight. Abraham will follow the road that helps him learn whether he’s a good man or a bad one. —Sonia. Don’t miss these related posts: Joe Jiménez contributed a revealing

Bloodlines, by Joe Jiménez, is a poetic vision of the complexities of (de)constructing Latino masculinities. Abraham is a seventeen-year-old figuring out what it means to be a man. He gets conflicting messages from the adults in his life. His grandmother wants him to be a good man so she solicits the help of her son Claudio, who Becky, grandma’s friend, doesn’t think is such a good man. Ophelia, Abraham’s love interest, wants Abraham to stop fighting but she also wonders what it feels like to fight. Abraham will follow the road that helps him learn whether he’s a good man or a bad one. —Sonia. Don’t miss these related posts: Joe Jiménez contributed a revealing  Burn Baby Burn, by Meg Medina, is set in Queens, New York, during the fateful year of 1978. While a serial killer prowls the city and arsonists torch random locations, Nora faces a disturbing issues at home. She has a sneaking suspicion that her brother is dabbling in dangerous activities, but their mom is too paralyzed to confront him head on. Nora’s story includes a supportive best friend, a cute guy who works at the same after-school job as Nora, and an apartment building full of complex and menacing characters. Also: disco dancing! Disco is a nice touch that, along with other historical elements, lends spark and crackle to an already intriguing story. We

Burn Baby Burn, by Meg Medina, is set in Queens, New York, during the fateful year of 1978. While a serial killer prowls the city and arsonists torch random locations, Nora faces a disturbing issues at home. She has a sneaking suspicion that her brother is dabbling in dangerous activities, but their mom is too paralyzed to confront him head on. Nora’s story includes a supportive best friend, a cute guy who works at the same after-school job as Nora, and an apartment building full of complex and menacing characters. Also: disco dancing! Disco is a nice touch that, along with other historical elements, lends spark and crackle to an already intriguing story. We  The Distance Between Us: Young Readers Edition, by Reyna Grande, is a memoir of astonishing power and relevance. Set in Mexico and California, it captures a decade of the author’s eventful life, intertwining elements of poverty, immigration, abandonment, and family strife. More than anything, it’s an account of personal triumph against enormous odds. I highly recommend it. To learn more, please see my

The Distance Between Us: Young Readers Edition, by Reyna Grande, is a memoir of astonishing power and relevance. Set in Mexico and California, it captures a decade of the author’s eventful life, intertwining elements of poverty, immigration, abandonment, and family strife. More than anything, it’s an account of personal triumph against enormous odds. I highly recommend it. To learn more, please see my  The Head of the Saint, by Socorro Acioli. Set Brazil and translated from Portuguese, this story is a dreamlike marvel. It follows a 14-year-old boy’s desperate journey toward reconnection and revenge. Destitute and rejected by his one living relative, he ends up living inside the hollow head of a broken statue of Saint Anthony. There, he magically hears the prayers of the village women, and to his consternation, gains celebrity status. One female voice sings her litany and captivates the boy’s heart, sight unseen. How can he find out who she is? The story is told in the language of fable and contains elements of magic realism. I found it irresistibly beautiful. Here’s our

The Head of the Saint, by Socorro Acioli. Set Brazil and translated from Portuguese, this story is a dreamlike marvel. It follows a 14-year-old boy’s desperate journey toward reconnection and revenge. Destitute and rejected by his one living relative, he ends up living inside the hollow head of a broken statue of Saint Anthony. There, he magically hears the prayers of the village women, and to his consternation, gains celebrity status. One female voice sings her litany and captivates the boy’s heart, sight unseen. How can he find out who she is? The story is told in the language of fable and contains elements of magic realism. I found it irresistibly beautiful. Here’s our  Lion Island: Cuba’s Warrior of Words, by Margarita Engle. Engle wraps up her series of books in verse that examine freedom and slavery in the Caribbean with this look at the Chinese community in 19th-century Cuba. Antonio is a Chinese-African boy, using his language skills to carry messages between Spanish and Chinese businessmen and diplomats. Through his job and his friendship with Chinese-American twins Wing and Fan, he learns about the persecution that forced the Chinese to flee California and the injustices they face as indentured laborers in Cuba. Meanwhile, rebels wage war against the Spanish, and as tensions grow, Antonio must decide how he is going to fight for freedom. An excellent choice for a classroom read-aloud or community book choice, especially now that Cuba is in the news again. —Cecilia

Lion Island: Cuba’s Warrior of Words, by Margarita Engle. Engle wraps up her series of books in verse that examine freedom and slavery in the Caribbean with this look at the Chinese community in 19th-century Cuba. Antonio is a Chinese-African boy, using his language skills to carry messages between Spanish and Chinese businessmen and diplomats. Through his job and his friendship with Chinese-American twins Wing and Fan, he learns about the persecution that forced the Chinese to flee California and the injustices they face as indentured laborers in Cuba. Meanwhile, rebels wage war against the Spanish, and as tensions grow, Antonio must decide how he is going to fight for freedom. An excellent choice for a classroom read-aloud or community book choice, especially now that Cuba is in the news again. —Cecilia The Memory of Light, by Francisco X. Stork. When Vicky Cruz wakes up in the hospital after a suicide attempt, she is sure that it’s only a matter of time before she will try again. But with the help of Dr. Desai and the other teens at the hospital, Vicky gains a better understanding of how to live with depression and how to take control of her future. That summary makes the book sound didactic, but it’s actually funny, thoughtful, and moving. This is the kind of book that you can open to any page and find wisdom and words to help you breathe and find strength. A hopeful, light-filled book that will help many readers–not just teens–face tomorrow with renewed courage. Check out our

The Memory of Light, by Francisco X. Stork. When Vicky Cruz wakes up in the hospital after a suicide attempt, she is sure that it’s only a matter of time before she will try again. But with the help of Dr. Desai and the other teens at the hospital, Vicky gains a better understanding of how to live with depression and how to take control of her future. That summary makes the book sound didactic, but it’s actually funny, thoughtful, and moving. This is the kind of book that you can open to any page and find wisdom and words to help you breathe and find strength. A hopeful, light-filled book that will help many readers–not just teens–face tomorrow with renewed courage. Check out our When the Moon Was Ours, by Anna-Marie McLemore. Miel and Sam have been friends ever since Miel emerged from the floodwaters of a toppled water tower. Each has secrets of their own, and now the Bonner sisters are determined to uncover them and steal the roses that grow out of Miel’s wrist. Gorgeous prose, and insights on love, family and gender identity make this a unique love story that is not to be missed. I’ve read this book about ten times now and each time I find new beauty that I missed before. A must-read for YA fans. —Cecilia

When the Moon Was Ours, by Anna-Marie McLemore. Miel and Sam have been friends ever since Miel emerged from the floodwaters of a toppled water tower. Each has secrets of their own, and now the Bonner sisters are determined to uncover them and steal the roses that grow out of Miel’s wrist. Gorgeous prose, and insights on love, family and gender identity make this a unique love story that is not to be missed. I’ve read this book about ten times now and each time I find new beauty that I missed before. A must-read for YA fans. —Cecilia Labyrinth Lost by Zoraida Córdova. Alex is a bruja, the most powerful witch in a generation…and she hates magic. At her Deathday celebration, Alex performs a spell to rid herself of her power. But it backfires. Her whole family vanishes into thin air, leaving her alone with Nova, a brujo boy she can’t trust. A boy whose intentions are as dark as the strange marks on his skin. The only way to get her family back is to travel with Nova to Los Lagos, a land in-between. Alex’s journey through Los Lagos feels very classic. The different communities she encounters, each with its own history and strengths and weaknesses, may remind readers of classic adventures like The Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, and Alice in Wonderland. Every new area of Los Lagos brings a ton of action. Not every writer can create battle scenes so the reader can clearly visualize them without having to re-read. Zoraida is GREAT at this. —Cecilia

Labyrinth Lost by Zoraida Córdova. Alex is a bruja, the most powerful witch in a generation…and she hates magic. At her Deathday celebration, Alex performs a spell to rid herself of her power. But it backfires. Her whole family vanishes into thin air, leaving her alone with Nova, a brujo boy she can’t trust. A boy whose intentions are as dark as the strange marks on his skin. The only way to get her family back is to travel with Nova to Los Lagos, a land in-between. Alex’s journey through Los Lagos feels very classic. The different communities she encounters, each with its own history and strengths and weaknesses, may remind readers of classic adventures like The Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, and Alice in Wonderland. Every new area of Los Lagos brings a ton of action. Not every writer can create battle scenes so the reader can clearly visualize them without having to re-read. Zoraida is GREAT at this. —Cecilia Gaby Rivera’s Juliet Takes a Breath is one of a kind. Rivera creates a beautiful, relatable, and necessary character in 19 year old Juliet Palante. Juliet comes out to her family the day she is set to travel to Oregon for an internship with a well renowned white feminist writer. Juliet is convinced that in order to be proudly lesbian she needs to leave her small and suffocating home in the Bronx. But this precious nena has so much to learn. Rivera takes Juliet on a journey of self-discovery that also allows the readers to learn about Latinx queer identity, history, and culture. After a few heartaches, let downs, and realizations, Juliet learns that the answers she seeks are where she least expects them. —Sonia