By Marilisa Jiménez García with Lehigh Students: Kristen Mejia, Felicia Galvez, Sarah White, Caroline Raney

This Spring 2017, I taught a course at Lehigh University called “Latinx Youth Culture.” The course centered on studying youth literature and culture from the perspective of how past and contemporary Latinx authors depict, and to an extent recover, history and youth protagonists. We also looked at ways in which many popular and award-winning books for Latinx youth, and those depicting Latinx young people and/or youth movements portrayed issues of race, gender, nationalism, and Latin American revolutions. Our reading list included:

Jose Marti, La Edad de Oro (1899)

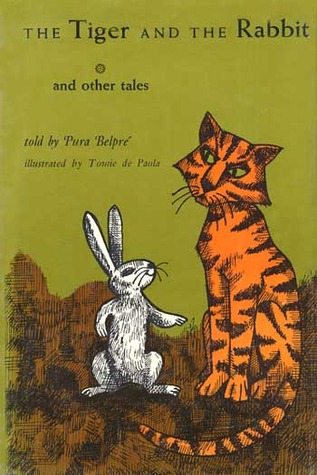

Pura Belpré, The Tiger and the Rabbit (1943)

Duncan Tonatiuh, Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote: A Migrant’s Tale (2013)

Nicholasa Mohr, Nilda (1973)

Pam Muñoz Ryan, Esperanza Rising (2000)

Sonia Manzano, The Revolution of Evelyn Serrano (2013)

Francisco Jimenez, The Circuit (1997)

Julia Alvarez, Before We Were Free (2004)

Margarita Engle, The Lightning Dreamer: Cuba’s Greatest Abolitionist (2013)

Ashley Hope Perez, Out of Darkness (2015)

Daniel José Older, Shadowshaper (2015)

As a class, we considered how these texts represent the Latinx community, and the history of Latin America and the Caribbean, to young readers, and in some cases, because of the lack of Latinx representation and authors in youth literature, these books may be the only portrayals a young reader may encounter in a book about Latinx people. At the end of the course, I asked students to create suggestions of what they hoped to see in Latinx literature for youth. What follows is a list of suggestions gathered from our collective conversation and survey of Latinx literature for youth, including comments composed by my students for those who are currently writing and those who hope to write for young readers. Students also kept in mind those in publishing and award committees.

Writers and award committees should pay more attention to their own racial and class biases in the Latinx community and internal struggles with anti-blackness. Students noted that many of the protagonists in award-winning and popular books are light-skinned Latinos, while Afro and Indigenous Latinxs characters tend to be marginalized as the supporting characters, in problematic tropes such as the servants and slave characters, and even the bullies. At that point, Daniel José Older’s Shadowshaper was the only prominent young adult novel we could survey with a strong Afro-Latinx protagonist. In terms of race and class privilege, students noted that often protagonists migrating to the U.S. from Latin America were of the upper class in terms of escaping dire circumstances, such as dictatorships. Particularly when it came to representing the Latinx past, and historical moments such as abolitionism in Latin America and the Caribbean and the Mexican Revolution, students noted that light-skinned Latinxs tended to model some of the “white savior tropes” familiar in European culture. As Felicia Galvez, a Lehigh sophomore noted:

“I think culture and race are important. It’s an issue that most Latinx youth are experiencing. To ignore that part and to deny it is wrong. Black characters that writers decide to put in books should not be stereotypical. It’s wrong. Latinxs can be racist. It is not just a U.S. thing. Most of these writers being nominated are privileged and are whiter. It needs to be said because there’s a pattern here. Latinxs are a diverse culture. They come in many different colors. It’s said that we only see the whiter side in the media and in literature. Don’t be afraid to criticize other Latinxs. We want to get our books out, but it shouldn’t come at the cost of someone feeling excluded from the picture or seeing themselves as a stereotypical black person. Or ignoring the suffering that they feel and that their ancestors felt. Writers should try harder to incorporate different perspectives in various ways. Having the main character react to people around them does not make me sympathize with the character. Having the side characters, of African descent, only reacting to the main character who is white is not okay. It’s annoying and sad because it promotes the idea that they need a white savior to help them…”

On researching the American Library Association’s Pura Belpré Medal, junior Caroline Raney, noted, “I was surprised to learn that in a literary genre founded with the goal of being inclusive and celebratory of the Latinx experience, there are still perspectives and backgrounds that are not being recognized. I am not of Latin American descent, so this was my first chance to critically read and analyze a lot of books classified as Latinx literature.” Raney took time to study the trends of the Medal since its founding in 1996, pointing out that a Belpré win may also mean a book is ordered more through libraries and schools, and perhaps more likely to be suggested in curriculum. Raney notes that in the event a Belpré Medal winner contained potentially anti-black and elitist view, then the “normalization of racism and privilege throughout the story may have widespread effects since this book may be the only piece of Latinx children’s literature many young Americans will ever read.”

Raney writes, “I think in the future, it is important to publish more children’s novels about more diverse Latinx backgrounds and perspectives as well as have more critical discussions about race in classrooms so that children can be able to recognize how some books can be problematic. As long as prize-winning Latinx children’s literature features predominantly privileged, white, and Spanish protagonists, the authentic stories of mixed, Afro-Latinx, and indigenous Latinx people living in Latin America and the United States today will be marginalized or even invisible. Including more diverse stories would not only help children see themselves in the novels they read, it could effect change by reducing bias and potentially racism in the future.”

Writers and publishers should make sure they research various perspectives during critical moments of Latin American and Caribbean history, such as the Mexican Revolution, the Cuban Revolution, El Grito de Lares, the Trujillo era in the Dominican Republic. Students also noted a relative silence about how and why those revolutions in Latin America happened, yet much more detail was present about political figures and movements in the U.S. Consider who gets to tell the story. Consider also whether, as Latinx writers, we are relying more on our families’ experiences and not going into research practices which enable us to see multiple perspectives in our home countries. Kristen Mejia, an outgoing senior reflects,

“Unfortunately, the books and authors I had read growing up hadn’t written about my experience about being a second-generation Latina and not being able to speak fluently…Writers should avoid story lines that are not validated within history. When writing a story line that utilizes history in some way, writers MUST DO THEIR HOMEWORK. DO NOT make up stories and events UNLESS there is a note after the novel explaining why this was done. Children grow up reading certain stories [and might believe those] stor[ies] [are] the only experience a [Mexican, a Cuban, etc.] could have at the time. [Many authors seem to rely on their own family’s experiences when recounting history] While many authors do this, and authors should do this, we also need to hold ourselves responsible for what image we are presenting to younger audiences. When utilizing history as a backdrop of a story, it is our duty as underrepresented Latinxs within literature, to use this opportunity to educate our youth. We can help them become more knowledge about their history and the history that our people have faced.”

Writers should consider whether they are truly presenting the consequences of historical events, such as slavery, revolution, and civil rights activism for young readers. Students appreciated when we read experiences that didn’t sugarcoat border-crossing and racial, gender, and sexual violence. Sarah White, a graduate student in American Studies, writes, “Writers should take care to avoid over-generalizations, stereotyping, and romantic/simplistic notions of their subjects. I would like to see stories that speak to current, relevant issues that youth today are dealing with, such as bullying, navigating multi-racial or transnational identities, and how to keep their heritage and culture alive in an era of increasing censorship and violence.”

Mejia notes, “Publishers need to avoid stories that paint difficult life events in a positive manner when in reality, they may always be hard and full of struggle. We need to be more real with our youth. Many young people grow up with an image of difficult times ending up being fine. Unfortunately, this is not everyone’s reality. Not every immigrant makes it across the border alive. Not everyone gets a rags-to-riches story. Our youth deserve more than just a fairy tale. They deserve to know what they may be faced with in our society and what they can do to prepare themselves for this struggle.”

Marilisa Jiménez García is an interdisciplinary scholar specializing in Latino/a literature and culture. She is particularly interested in the intersections of race, gender, nationalism, and youth culture in Puerto Rican literature of the diaspora. Jiménez García also specializes in literature for youth and how marginalized communities have used children’s and young adult texts as a platform for artistic expression, collective memory, and community advocacy. She is working on a book manuscript on the formation of Latino/a literature and media for youth. She has published in venues such as CENTRO Journal, Journal for the History of Childhood and Youth, Latino Studies, and Journal for Adolescent and Adult Literacy. Before joining Lehigh University, Jiménez García held a postdoctoral research appointment as a research associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies (CENTRO) at Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY). She was also an adjunct assistant professor in the Africana/Puerto Rican/Latino Studies department at Hunter College. She is the recipient of a Cultivating New Voices Among Scholars of Color Fellowship from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and a Best Dissertation Award from the Puerto Rican Studies Association (PRSA). Jiménez García has also completed service projects in New York City public schools and with the Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools. She has forthcoming book chapters on the Pura Belpré Medal and intersectionality in ethnic literature for Routledge and Teachers College Press, respectively. Jiménez García completed her Ph.D. in 2012 from the University of Florida.

Marilisa Jiménez García is an interdisciplinary scholar specializing in Latino/a literature and culture. She is particularly interested in the intersections of race, gender, nationalism, and youth culture in Puerto Rican literature of the diaspora. Jiménez García also specializes in literature for youth and how marginalized communities have used children’s and young adult texts as a platform for artistic expression, collective memory, and community advocacy. She is working on a book manuscript on the formation of Latino/a literature and media for youth. She has published in venues such as CENTRO Journal, Journal for the History of Childhood and Youth, Latino Studies, and Journal for Adolescent and Adult Literacy. Before joining Lehigh University, Jiménez García held a postdoctoral research appointment as a research associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies (CENTRO) at Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY). She was also an adjunct assistant professor in the Africana/Puerto Rican/Latino Studies department at Hunter College. She is the recipient of a Cultivating New Voices Among Scholars of Color Fellowship from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and a Best Dissertation Award from the Puerto Rican Studies Association (PRSA). Jiménez García has also completed service projects in New York City public schools and with the Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools. She has forthcoming book chapters on the Pura Belpré Medal and intersectionality in ethnic literature for Routledge and Teachers College Press, respectively. Jiménez García completed her Ph.D. in 2012 from the University of Florida.

Q: I know you’ve talked about how you love to visit botanical gardens, which inspired La Pradera. Which gardens would you recommend people try and visit?

Q: I know you’ve talked about how you love to visit botanical gardens, which inspired La Pradera. Which gardens would you recommend people try and visit?

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at  Celia C. Pérez

Celia C. Pérez

Cindy L. Rodriguez

Cindy L. Rodriguez DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: As a young boy, Jose Martí traveled to the countryside of Cuba and fell in love with the natural beauty of the land. During this trip he also witnessed the cruelties of slavery on sugar plantations. From that moment, Martí began to fight for the abolishment of slavery and for Cuban independence from Spain through his writing. By age seventeen, he was declared an enemy of Spain and was forced to leave his beloved island. Martí traveled the world and eventually settled in New York City. But the longer he stayed away from his homeland, the sicker and weaker he became. On doctor’s orders he traveled to the Catskill Mountains, where nature inspired him once again to fight for freedom. Here is a beautiful tribute to Jose Martí, written in verse with excerpts from his seminal work, Versos sencillos. He will always be remembered as a courageous fighter for freedom and peace among all men and women.

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: As a young boy, Jose Martí traveled to the countryside of Cuba and fell in love with the natural beauty of the land. During this trip he also witnessed the cruelties of slavery on sugar plantations. From that moment, Martí began to fight for the abolishment of slavery and for Cuban independence from Spain through his writing. By age seventeen, he was declared an enemy of Spain and was forced to leave his beloved island. Martí traveled the world and eventually settled in New York City. But the longer he stayed away from his homeland, the sicker and weaker he became. On doctor’s orders he traveled to the Catskill Mountains, where nature inspired him once again to fight for freedom. Here is a beautiful tribute to Jose Martí, written in verse with excerpts from his seminal work, Versos sencillos. He will always be remembered as a courageous fighter for freedom and peace among all men and women. ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Emma Otheguy is a children’s book author and a historian of Spain and colonial Latin America. She is a member of the Bank Street Writers Lab, and her short story “Fairies in Town” was awarded a Magazine Merit Honor by the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI). Otheguy lives with her husband in New York City. Martí’s Song for Freedom/Martí y sus versos por la libertad is her picture book debut. You can find her online at

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Emma Otheguy is a children’s book author and a historian of Spain and colonial Latin America. She is a member of the Bank Street Writers Lab, and her short story “Fairies in Town” was awarded a Magazine Merit Honor by the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI). Otheguy lives with her husband in New York City. Martí’s Song for Freedom/Martí y sus versos por la libertad is her picture book debut. You can find her online at  ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Beatriz Vidal was born in Argentina and attended the Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities of Cordoba University. In New York, she studied painting and design with Ilonka Karasz for several years. During that time, her career as an illustrator began with designs for Unicef cards and record covers. She has illustrated many children’s books, including The Legend of El Dorado, A Library for Juana, Federico and the Magi’s Gift, and A Gift of Gracias. She divides her time between Buenos Aires and New York City.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Beatriz Vidal was born in Argentina and attended the Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities of Cordoba University. In New York, she studied painting and design with Ilonka Karasz for several years. During that time, her career as an illustrator began with designs for Unicef cards and record covers. She has illustrated many children’s books, including The Legend of El Dorado, A Library for Juana, Federico and the Magi’s Gift, and A Gift of Gracias. She divides her time between Buenos Aires and New York City. ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Chantel Acevedo’s novels include

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Chantel Acevedo’s novels include

Marilisa Jiménez García is an interdisciplinary scholar specializing in Latino/a literature and culture. She is particularly interested in the intersections of race, gender, nationalism, and youth culture in Puerto Rican literature of the diaspora. Jiménez García also specializes in literature for youth and how marginalized communities have used children’s and young adult texts as a platform for artistic expression, collective memory, and community advocacy. She is working on a book manuscript on the formation of Latino/a literature and media for youth. She has published in venues such as CENTRO Journal, Journal for the History of Childhood and Youth, Latino Studies, and Journal for Adolescent and Adult Literacy. Before joining Lehigh University, Jiménez García held a postdoctoral research appointment as a research associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies (CENTRO) at Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY). She was also an adjunct assistant professor in the Africana/Puerto Rican/Latino Studies department at Hunter College. She is the recipient of a Cultivating New Voices Among Scholars of Color Fellowship from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and a Best Dissertation Award from the Puerto Rican Studies Association (PRSA). Jiménez García has also completed service projects in New York City public schools and with the Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools. She has forthcoming book chapters on the Pura Belpré Medal and intersectionality in ethnic literature for Routledge and Teachers College Press, respectively. Jiménez García completed her Ph.D. in 2012 from the University of Florida.

Marilisa Jiménez García is an interdisciplinary scholar specializing in Latino/a literature and culture. She is particularly interested in the intersections of race, gender, nationalism, and youth culture in Puerto Rican literature of the diaspora. Jiménez García also specializes in literature for youth and how marginalized communities have used children’s and young adult texts as a platform for artistic expression, collective memory, and community advocacy. She is working on a book manuscript on the formation of Latino/a literature and media for youth. She has published in venues such as CENTRO Journal, Journal for the History of Childhood and Youth, Latino Studies, and Journal for Adolescent and Adult Literacy. Before joining Lehigh University, Jiménez García held a postdoctoral research appointment as a research associate at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies (CENTRO) at Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY). She was also an adjunct assistant professor in the Africana/Puerto Rican/Latino Studies department at Hunter College. She is the recipient of a Cultivating New Voices Among Scholars of Color Fellowship from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) and a Best Dissertation Award from the Puerto Rican Studies Association (PRSA). Jiménez García has also completed service projects in New York City public schools and with the Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools. She has forthcoming book chapters on the Pura Belpré Medal and intersectionality in ethnic literature for Routledge and Teachers College Press, respectively. Jiménez García completed her Ph.D. in 2012 from the University of Florida.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: