By David Bowles

By David Bowles

Pretty soon after Summer of the Mariposas was published by Tu Books in 2012, teachers in the US started asking for a Spanish translation. This story of Mexican-American sisters who go on an odyssey into Mexico, confronting obstacles both supernatural and all-too-human, resonated with Latinx readers, and teachers especially wanted immigrant children and other Spanish-dominant ELLs to have full access to the narrative.

But author Guadalupe García McCall (and editor Stacy Whitman) had a very specific vision for the translation. The novel is narrated by Odilia Garza, oldest of the sisters, and it was important that her voice stay true to that of border girls like Guadalupe, even in Spanish.

Ideally, that vision meant hiring a Mexican-American from the Texas-Mexico border to translate the novel.

Five years later, Stacy approached me (full disclosure: she’s publishing a graphic novel that Raúl the Third and I created, Clockwork Curandera). I was excited at the chance to translate a book that I loved and had been teaching at the University of Texas Río Grande Valley, one written by a great friend, to boot!

Guadalupe and I dug in at once. As I translated, she was always available as a sounding board. I’ve discussed the particulars of our collaborative process on the Lee and Low Blog as well as in the journal Bookbird, but here I want to focus on a particular post-publication issue.

Some people just don’t like the translation.

Specifically, a couple of reviews—in Kirkus and elsewhere—fault the Spanish used in the translation as occasionally a “word-for-word” echo of the English, replete with Anglicisms.

Fair enough. I’m not going to actually claim there’s no truth to the critique. But there are some things you should definitely know before you leap to judgment.

The most important one is … most of that English flavor? It’s on purpose.

Quick digression. When I hear these sorts of complaints, they feel to me like code for one or more of the following: 1) this doesn’t read like typical juvenile literature written in Spanish; 2) this isn’t a recognizable Latin-American dialect of Spanish; 3) this feels too English-y in its syntax (though not ungrammatical); and 4) this has been clearly translated by someone who grew up in the US and was schooled primarily in English.

What none of those points takes into account is an obvious and pivotal fact. This book is a first-person narrative, by a Mexican-American teen. The strange Spanish? It’s how she sounds.

Guadalupe Garcia McCall and David Bowles

Let’s talk for a minute about Guadalupe García McCall and David Bowles. Both Mexican-American (yes, I’m half Anglo, but my family is Mexican-American and I identify as such). Both from the border (Eagle Pass/Piedras Negras versus McAllen/Reynosa). Both schooled EXCLUSIVELY in English (no bilingual education, no early efforts to promote our Spanish literacy). Both of us were robbed of that linguistic heritage. Both of us went on to earn degrees in English that we used to teach middle- and high-school English courses.

Our native dialect is border Spanish. Pocho Spanish, some would rudely put it. Rife with English syntax and borrowings, centuries-old forms and words that the rest of Latin-American might giggle or roll their collective eyes at. But it’s Spanish, yes it is. Aunque no te guste.

Now, I started studying formal Spanish in high school, then went on to minor in it for my BA and MA. I ended up teaching AP Spanish Literature for a time, etc. This process gave me a second, formal, literary dialect. I also have lived in Mexico, and I married a woman born in Monterrey. That’s where my third dialect arises, a version of Northern Mexican Spanish.

So, when I set out with Guadalupe to craft the voice of a border kid who loves to read and still has roots in Mexico, this mestizaje of Spanish dialects is what we hit upon.

It amazes me to no end that writers can do odd and/or regional dialogues all the time in English, but a similar attempt in Spanish elicits disapproving frowns.

I’m sorry, but not all books need to be translated into some neutral, RAE-approved literary Spanish. Some are so deeply rooted in a place, in a community, that we have to insist on breaking “the rules.”

To wrap this apologia up, I’ll just toss out two excerpts from chapter 8. No critic has added specifics to their negative reviews, but I will.

As a counter to the implication that the translation is too word-for-word, let’s look at this passage.

“Yup. According to this, the National Center for Missing and Exploded Children is looking for us,” Velia continued reading on.

“Exploited,” I corrected.

“What?” Velia asked, looking at me like I was confusing her.

“Exploi-t-ed, not exploded,” I explained. “The National Center for Missing and Exploi-t-ed Children.”

“Whatever,” Velia said.

Here’s the Spanish version.

—Pos, sí. Según esto, el Centro Nacional de Niños Desaparecidos y Explotados nos está buscando —continuó Velia—. Qué bueno que en nuestro caso no hay bombas.

—Claro que no hay bombas, mensa —corregí.

—¿Cómo? —preguntó Velia, mirándome como si la confundiera.

—Explotados en el sentido de “usados para cosas malas”, no explotados como “volados en pedazos por una bomba” —expliqué—. Ese centro busca a niños secuestrados, esclavizados, etcétera.

—Ah, órale —dijo Velia.

With the exception of “mirándome como si la confundiera” (someone else might’ve said “con una mirada confundida” or some other less English-y variation), the passage doesn’t ape the English at all. Sure, I can see some Spanish speakers objecting to “como si la confundiera,” expecting it to be followed by “con X cosa” (confusing her with X thing). But, yikes, this is pretty much the way lots of border folks would say it.

The other example is from the first paragraph of the chapter:

After I got back to the dead man’s house, I told Inés they were all out of newspapers, then we ate breakfast in record time.

Cuando volví a la casa del difunto, le dije a Inés que ya se habían agotado los periódicos y luego desayunamos en tiempo récord.

Yes. Each part of that Spanish sentence is a (grammatically correct) mirror of its English equivalent.

Yes. There are multiple ways to have translated it more freely so that it doesn’t echo the original as much.

Yes. There are more “Mexican” ways of saying “in record time” than the (still pretty common) Anglicism “en tiempo récord.”

But that’s not what we were going for here. As a result, some people are going to not like my translation, just like some editors don’t like the peculiar voices of writers of color in English, with their code-switching and so on.

There are gatekeepers everywhere. Pero me vale.

ABOUT THE WRITER-TRANSLATOR: A Mexican-American author from deep South Texas, David Bowles is an assistant professor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Recipient of awards from the American Library Association, Texas Institute of Letters and Texas Associated Press, he has written thirteen titles, most notably the Pura Belpré Honor Book The Smoking Mirror and the critically acclaimed Feathered Serpent, Dark Heart of Sky: Mexican Myths, and They Call Me Güero: A Border Kid’s Poems. In 2019, Penguin will publish The Chupacabras of the Rio Grande, co-written with Adam Gidwitz as part of The Unicorn Rescue Society series, and Tu Books will release his steampunk graphic novel Clockwork Curandera. His work has also appeared in multiple venues such as Journal of Children’s Literature, Rattle, Strange Horizons, Apex Magazine, Translation Review, and Southwestern American Literature.

ABOUT THE WRITER-TRANSLATOR: A Mexican-American author from deep South Texas, David Bowles is an assistant professor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Recipient of awards from the American Library Association, Texas Institute of Letters and Texas Associated Press, he has written thirteen titles, most notably the Pura Belpré Honor Book The Smoking Mirror and the critically acclaimed Feathered Serpent, Dark Heart of Sky: Mexican Myths, and They Call Me Güero: A Border Kid’s Poems. In 2019, Penguin will publish The Chupacabras of the Rio Grande, co-written with Adam Gidwitz as part of The Unicorn Rescue Society series, and Tu Books will release his steampunk graphic novel Clockwork Curandera. His work has also appeared in multiple venues such as Journal of Children’s Literature, Rattle, Strange Horizons, Apex Magazine, Translation Review, and Southwestern American Literature.

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK (from

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK (from

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (from  ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Katrina Ortega (M.L.I.S.) is the Young Adult Librarian at the Hamilton Grange Branch of the New York Public Library. Originally from El Paso, Texas, she has lived in New York City for six years. She is a strong advocate of continuing education (in all of its forms) and is very interested in learning new ways that public libraries can provide higher education to all. She is also very interested in working with non-traditional communities in the library, particularly incarcerated and homeless populations. While pursuing her own higher education, she received two Bachelors of Arts degrees (in English and in History), a Masters of Arts in English, and a Masters of Library and Information Sciences. Katrina loves reading most anything, but particularly loves literary fiction, YA novels, and any type of graphic novel or comic. She’s also an Anglophile when it comes to film and TV, and is a sucker for British period pieces. In her free time, if she’s not reading, Katrina loves to walk around New York, looking for good places to eat.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Katrina Ortega (M.L.I.S.) is the Young Adult Librarian at the Hamilton Grange Branch of the New York Public Library. Originally from El Paso, Texas, she has lived in New York City for six years. She is a strong advocate of continuing education (in all of its forms) and is very interested in learning new ways that public libraries can provide higher education to all. She is also very interested in working with non-traditional communities in the library, particularly incarcerated and homeless populations. While pursuing her own higher education, she received two Bachelors of Arts degrees (in English and in History), a Masters of Arts in English, and a Masters of Library and Information Sciences. Katrina loves reading most anything, but particularly loves literary fiction, YA novels, and any type of graphic novel or comic. She’s also an Anglophile when it comes to film and TV, and is a sucker for British period pieces. In her free time, if she’s not reading, Katrina loves to walk around New York, looking for good places to eat. By Cecilia Cackley

By Cecilia Cackley

ABOUT THE AUTHORAbout the author: Jen Cervantes is an award-winning children’s author. In addition to other honors, she was named a New Voices Pick by the American Booksellers Association for her debut novel, Tortilla Sun. The Storm Runner‘s sequel, entitled The Fire Keeper, is slated for release in 2019. Keep up with Jen’s books and appearances at her

ABOUT THE AUTHORAbout the author: Jen Cervantes is an award-winning children’s author. In addition to other honors, she was named a New Voices Pick by the American Booksellers Association for her debut novel, Tortilla Sun. The Storm Runner‘s sequel, entitled The Fire Keeper, is slated for release in 2019. Keep up with Jen’s books and appearances at her  ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER: Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. Learn more at

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER: Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. Learn more at

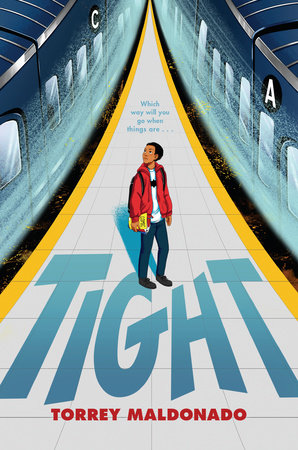

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: What do you get from teaching nearly 20 years in a middle school in the Brooklyn community that you’re from & you’re an author? Gripping relatable novels and real-life inspiration. Voted a “Top 10 Latino Author” & best Middle Grade & Young Adult novelist for African Americans, Torrey Maldonado was spotlighted as a top teacher by NYC’s former Chancellor. Maldonado is the author of the ALA “Quick Pick”,

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: What do you get from teaching nearly 20 years in a middle school in the Brooklyn community that you’re from & you’re an author? Gripping relatable novels and real-life inspiration. Voted a “Top 10 Latino Author” & best Middle Grade & Young Adult novelist for African Americans, Torrey Maldonado was spotlighted as a top teacher by NYC’s former Chancellor. Maldonado is the author of the ALA “Quick Pick”,  ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Lila Quintero Weaver is the author of a graphic memoir,

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Lila Quintero Weaver is the author of a graphic memoir,