Reviewed by Lila Quintero Weaver

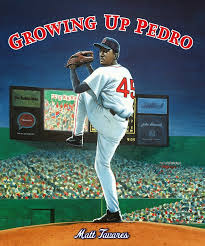

FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Before Pedro Martinez pitched the Red Sox to a World Series championship, before he was named to the All-Star team eight times, before he won the Cy Young Award three times, he was a kid from a place called Manoguayabo in the Dominican Republic. Pedro loved baseball more than anything, and his brother Ramón was the best pitcher he’d ever seen. He dreamed of the day he and his brother could play together in the major leagues. This is the story of how that dream came true. Matt Tavares has crafted a fitting homage to a modern-day baseball star that examines both his improbable rise to the top of his game and the power that comes from the bond between brothers.

MY TWO CENTS: The author-illustrator Matt Tavares makes beautiful picture books, many of which explore stories from baseball. His sports biographies for young readers include Henry Aaron’s Dream, There Goes Ted Williams, and Becoming Babe Ruth. In Growing Up Pedro, Dominican major league pitcher Pedro Martinez takes a turn in the spotlight. At the peak of Martinez’s brilliant career, he pitched for the Boston Red Sox. In 2004, his performance in Game 3 helped the team capture a long-sought World Series championship. Martinez’s story abounds with tall achievements, but there are other, smaller points of inspiration in his journey, and this combination makes him an ideal hero for kid readers.

Just as the title implies, Growing Up Pedro traces Martinez’s rise to baseball glory back to childhood years. As the story begins, young Martinez sits on the sidelines, riveted by his older brother Ramón’s ability to fire fastballs. Ramón is good—really good—but even as he pursues his own baseball dreams, Ramón takes the time to teach Pedro everything he knows about pitching. Sometimes they practice their aim on mangos, still clinging to the branches. When Ramón is drafted by the Los Angeles Dodgers, Pedro continues honing his skills on his own and ultimately captures the attention of U.S. talent scouts. After he joins his brother in Los Angeles, Pedro faces new challenges. He must work hard to prove himself to critics who consider him too small-framed to succeed as a major-leaguer. Before it’s all over, Martinez perfects a 97-mph fastball, wins the prestigious Cy Young Award multiple times, captures a World Series title, and lands a spot in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Growing Up Pedro succeeds on multiple levels. First, it’s a story of dreaming big and achieving bigger. The narrative emphasizes that talent plus hard work make it possible for this young boy to rise out of obscurity and poverty. In one illustration, Pedro is shown alone, practicing outdoors at sunset. With Ramón already in the United States, Pedro’s internal drive to excel is what keeps him going, throwing pitch after pitch in the dying light.

As already noted, this picture book offers a warm portrayal of the family bonds that carry both brothers into the ranks of professional sports. One vignette shows them dreaming aloud: “At night, they lie awake, two to a mattress, and talk about what they will do when they are millionaires.”

Growing Up Pedro also gives satisfying glimpses of rural Caribbean life, and it drives home the importance of baseball in the Dominican culture. At Campo Las Palmas, a Dodgers’ facility in the Dominican Republic, dozens of boys go through the thirty-day tryout alongside Pedro.

Matt Tavares’s illustrations command attention. The soft colors of his landscapes suggest sunshine diffused by tropical humidity. Mountains draped in lush vegetation fill the backdrops of the Dominican scenes. In the second part of the story, Pedro’s world switches to baseball stadiums packed with cheering fans, dressed in Red Sox team colors. One powerful illustration zooms in on Martinez’s face as he stands at the pitcher’s mound. His eyes contain supreme focus and reflect years of devotion to his sport. The accompanying text reads: “…when it is his turn to pitch, Pedro is very serious. All day, he is quiet and focused. When he takes the mound, he imagines he is a lion fighting for his food.” (This image is available for viewing on the author’s website, linked below in his bio.)

Toward the end of the book, the narrative circles back around to the Dominican Republic. When an injured Pedro nevertheless pitches and sends the Red Sox into the American League Championship Series, Tavares’s paintbrush fills in scenes of celebration on the home front, where fans gather in front of television sets to watch Pedro. Following his success, “people dance in the streets. Kids tie scraps of metal to their bikes and ride through the darkness. Sparks light up the night like fireworks.” This is a transcendent moment that extends the hero’s journey into something bigger than himself, into a victory for all his people and for other dreamers, near and far.

Matt Tavares is a prolific writer and illustrator of children’s books. His work has received starred reviews and high honors, including three Parents’ Choice Gold Awards, six Oppenheim Gold Seal Awards, and an International Reading Association Children’s Book Award. Matt’s original artwork has been exhibited at major museums. He’s a popular speaker and presenter to adult and child audiences alike. Visit his official website to learn more.

TEACHING RESOURCES:

Visit Pedro Martinez’s page on the National Baseball Hall of Fame site.

The Dominican Republic boasts a jaw-dropping number of players in the ranks of professional baseball. This website provides an informative chart.

Watch a highlights video of Martinez pitching a 17-strikeout game in 1999.

Lila Quintero Weaver is the author-illustrator of Darkroom: A Memoir in Black & White. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Darkroom recounts her family’s immigrant experience in small-town Alabama during the tumultuous 1960s. It is her first major publication. Lila is a graduate of the University of Alabama. She and her husband, Paul, are the parents of three grown children. She can also be found on her own website, Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

Lila Quintero Weaver is the author-illustrator of Darkroom: A Memoir in Black & White. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Darkroom recounts her family’s immigrant experience in small-town Alabama during the tumultuous 1960s. It is her first major publication. Lila is a graduate of the University of Alabama. She and her husband, Paul, are the parents of three grown children. She can also be found on her own website, Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

The Cuba I Know

The Cuba I Know