In my memoir, The Distance Between Us, I write about my experience as a border crosser. Borders have always been a part of my life. It saddens me to see that the world—instead of tearing down border walls—is actually building more of them. There are more border barriers today than ever before. In 1989 there were only 15 border walls in the world. Today there are more than 63, and counting.

In my memoir, The Distance Between Us, I write about my experience as a border crosser. Borders have always been a part of my life. It saddens me to see that the world—instead of tearing down border walls—is actually building more of them. There are more border barriers today than ever before. In 1989 there were only 15 border walls in the world. Today there are more than 63, and counting.

The author’s childhood home

My first experience with borders came at the age of two when my father left Mexico to seek a better life in the U.S. Two years later, my mother also left to the land across the border, leaving me and my siblings behind. By the time I was five, I had no mother and no father with me, and a border stood between us, separating us. I was left behind to yearn for the day when my family would be reunited.

Reyna (center) and siblings Carlos & Mago

At the age of nine I found myself face to face with that border. I had to run across it, become a ‘criminal’, break U.S. law for a chance to have a father again. I succeeded on my third attempt and began my new life in Los Angeles at my father’s house. I thought I was done with borders; I didn’t know there would be more to be crossed—cultural borders, language borders, legal borders, gender and career borders, and more.

As a Mexican immigrant, as a woman of color, as a Latina writer I’ve fought to break down the barriers American society puts up for the groups I belong to. It’s always been a struggle to be Mexican in this country, and especially so in these dark times. For over a year Mexican immigrants had been under attack, blatantly demeaned and vilified by Donald Trump, who began his presidential campaign by calling Mexicans rapists, drug dealers, criminals. He said he would literally build more border walls, and now that he’s been elected president, we will bear witness to his hatred of my people. But he’s wrong about many things—especially when he said that Mexico doesn’t send its best. Like most Mexican immigrants, I have given nothing but my best to this country since the moment I crossed the U.S. border. I’ve worked hard at learning the language, understanding the American way of life, at pursuing my education, honing my writing craft, so that one day I could be a contributing member of this society and use my skills and passion to keep this country great. This is what most immigrants do. Our work ethic, our drive, our perseverance, our passion, our commitment to succeed and to give our best is undeniable.

Reyna in her college years

Being a woman has never been easy. In the U.S. we might have it better than other countries, but still, women here have always struggled to overcome the borders put before us. We’ve had a long battle to redefine our place in the home and the workplace, our right to earn equal pay to what men receive. To be seen as more than someone’s daughter, wife, or mother. We had a long fight for our right to vote and to have a political voice, and for the past year we were fighting for our right to lead. For the first time we could have had our first female president since the birth of this nation, but despite her qualifications, since the very beginning of her campaign, Hillary Clinton was held to a double-standard because of her gender. Because she was a woman. We let that man get away with saying the most insulting, offensive, and ridiculous things. But Clinton? We let her get away with nothing. We elected a man who has absolutely no experience in running a country, instead of the woman who was more than qualified to do that and more.

We witnessed, at a national level, what happens on a daily basis to women in the workplace—we lose to men who are less qualified than us.

Last week we bore witness to a white woman failing to tear down the wall put before her by a sexist, patriarchal society. The fight is even harder for women of color who struggle not just against gender inequality but racial inequality. Since race impacts our feminism, we’ve always fought two battles at the same time. As a woman of color, I fight for equality but I also fight for justice. For us women of color, it isn’t enough to integrate ourselves into the existing system. We seek to transform the system and end injustices.

As a Latina writer, I’ve been dealing with other kinds of borders throughout my career. Latinos are 17.4 % of U.S. population, around 55 million of us, but we’re only around 4% of working professionals— including artists, writers, actors. We’re often kept on the periphery of the arts—and we fight on a daily basis for the right to contribute our stories, our talent, our creativity to American identity and culture. Through our art, we aim to fight against the barrier of invisibility. If we aren’t in books, in film, in TV, in art galleries, in music, does that mean we don’t exist?

The publishing industry lacks diversity at every level. The majority of books are written by, and are about, white people. Eighty-two percent of editors are white. Eighty-nine percent of book reviewers are white. They’re la migra of the publishing industry, the border patrol. They decide who gets in and who doesn’t, who gets published, whose books get attention. Latino writers have often struggled to get across the border of the mainstream publishing industry, often ending up with tiny presses (who lack the resources to do right by them) or self-publishing.

But having successfully run across the U.S. border at the age of nine taught me one thing—I can cross any border. This is the biggest reason why I wrote The Distance Between Us. I want to inspire others to believe in themselves and to find the strength to overcome. It is this belief that has helped me succeed in ways I never dreamed of. I want to encourage our youth, immigrant and non-immigrant alike, to keep giving their best and continue striving toward their dreams, despite the obstacles they find along the way.

Now more than ever, let us continue fighting for social justice, for a world without borders, for our right to create art, for our voices to be heard. It is through our stories that we will build bridges and tear down walls.

Reyna Grande is the award-winning author of two novels and a memoir, The Distance Between Us, which was recently published as a young readers edition. See our review here, where you may also learn more about Reyna’s story and watch video interviews. Her official website offers additional information about her published works, speaking schedule, and career news.

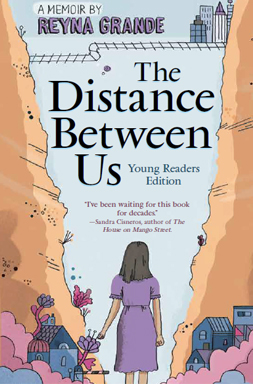

(Left) The original version of The Distance Between Us; (right) the young readers edition.

Sunday, at the age of 32, I went to my first demonstration. My husband and I took the kids and gathered with about 500 neighbors for a peaceful, family-friendly vigil and march. Our goal: to come together in response to acts of intimidation and intolerance in Columbus. We wanted to show that there’s no place for hate in our community.

Sunday, at the age of 32, I went to my first demonstration. My husband and I took the kids and gathered with about 500 neighbors for a peaceful, family-friendly vigil and march. Our goal: to come together in response to acts of intimidation and intolerance in Columbus. We wanted to show that there’s no place for hate in our community.

by Cecilia Cackley

by Cecilia Cackley That sense of exploration is on full display in Juana and Lucas, which features a loose, sketchy quality to the ink drawings. Medina points to the British illustrator Quentin Blake as a key influence, noting that he draws with both hands, and she often does too, or sometimes draws with one hand and colors with the other. Another favorite artist is Joaquin Salvador Lavado, better known by his pen name Quino, who created the iconic comic strip Mafalda for the Argentine newspaper El Mundo. Medina gushes about Quino’s “level of expressiveness.” She points out: “He includes wit in such simple traces and achieves complexity and an incredible level of detail in just a few lines.”

That sense of exploration is on full display in Juana and Lucas, which features a loose, sketchy quality to the ink drawings. Medina points to the British illustrator Quentin Blake as a key influence, noting that he draws with both hands, and she often does too, or sometimes draws with one hand and colors with the other. Another favorite artist is Joaquin Salvador Lavado, better known by his pen name Quino, who created the iconic comic strip Mafalda for the Argentine newspaper El Mundo. Medina gushes about Quino’s “level of expressiveness.” She points out: “He includes wit in such simple traces and achieves complexity and an incredible level of detail in just a few lines.” For Juana and Lucas, Medina experimented with sketches in pencil first, then used a light box to draw the final version of each illustration in ink. Watercolor came next and the drawing was then scanned so that the colors could be adjusted digitally. This process also allowed Medina to correct small errors without having to redraw an entire composition. She showed me one spread containing an airplane that hadn’t been in the original sketch. Later in the process, it was added digitally to cover up an unruly inkblot!

For Juana and Lucas, Medina experimented with sketches in pencil first, then used a light box to draw the final version of each illustration in ink. Watercolor came next and the drawing was then scanned so that the colors could be adjusted digitally. This process also allowed Medina to correct small errors without having to redraw an entire composition. She showed me one spread containing an airplane that hadn’t been in the original sketch. Later in the process, it was added digitally to cover up an unruly inkblot!

The dynamic presentation of text (words that curve, get bigger or in other ways deviate from the standard type) featured throughout the story was Medina’s idea. Her thinking is that typography is part of language, explored, and it can cue certain meanings of words that may be unfamiliar to young readers.

The dynamic presentation of text (words that curve, get bigger or in other ways deviate from the standard type) featured throughout the story was Medina’s idea. Her thinking is that typography is part of language, explored, and it can cue certain meanings of words that may be unfamiliar to young readers. For readers in the United States used to seeing European cities such as London or Paris in children’s literature, it’s a breath of fresh air to get such a detailed, child’s-eye view of a major South American city. Medina went back to Bogotá after writing several versions, and says the trip was bittersweet. “It was the first time there without my grandparents, without having a place there to call home. It was a difficult trip, but it was sweet to see the mountains and smell the eucalyptus, and it was validating to see everything. I took some license in the book. I’m not tying myself to fact-checking everything, which was liberating in a way. There was a lot I left out, especially surrounding the conflict and civil war I grew up with. That’s something I’ll maybe address in another book. The hardest illustration was my grandparents’ house, which no longer exists. It was a safe haven, so no illustration could truly do it justice.”

For readers in the United States used to seeing European cities such as London or Paris in children’s literature, it’s a breath of fresh air to get such a detailed, child’s-eye view of a major South American city. Medina went back to Bogotá after writing several versions, and says the trip was bittersweet. “It was the first time there without my grandparents, without having a place there to call home. It was a difficult trip, but it was sweet to see the mountains and smell the eucalyptus, and it was validating to see everything. I took some license in the book. I’m not tying myself to fact-checking everything, which was liberating in a way. There was a lot I left out, especially surrounding the conflict and civil war I grew up with. That’s something I’ll maybe address in another book. The hardest illustration was my grandparents’ house, which no longer exists. It was a safe haven, so no illustration could truly do it justice.”

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at  The

The  DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Anita de la Torre never questioned her freedom living in the Dominican Republic. But by her 12th birthday in 1960, most of her relatives have emigrated to the United States, her Tío Toni has disappeared without a trace, and the government’s secret police terrorize her remaining family because of their suspected opposition of el Trujillo’s dictatorship.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Anita de la Torre never questioned her freedom living in the Dominican Republic. But by her 12th birthday in 1960, most of her relatives have emigrated to the United States, her Tío Toni has disappeared without a trace, and the government’s secret police terrorize her remaining family because of their suspected opposition of el Trujillo’s dictatorship. DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: After Tyler’s father is injured in a tractor accident, his family is forced to hire migrant Mexican workers to help save their Vermont farm from foreclosure. Tyler isn’t sure what to make of these workers. Are they undocumented? And what about the three daughters, particularly Mari, the oldest, who is proud of her Mexican heritage but also increasingly connected to her American life. Her family lives in constant fear of being discovered by the authorities and sent back to the poverty they left behind in Mexico. Can Tyler and Mari find a way to be friends despite their differences?

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: After Tyler’s father is injured in a tractor accident, his family is forced to hire migrant Mexican workers to help save their Vermont farm from foreclosure. Tyler isn’t sure what to make of these workers. Are they undocumented? And what about the three daughters, particularly Mari, the oldest, who is proud of her Mexican heritage but also increasingly connected to her American life. Her family lives in constant fear of being discovered by the authorities and sent back to the poverty they left behind in Mexico. Can Tyler and Mari find a way to be friends despite their differences? ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: