Review by Cris Rhodes

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: It’s the summer of 1911 in northern Mexico, and thirteen-year-old Evangelina and her family have learned that the rumors of soldiers in the region are true. Her father decides they must leave their home to avoid the violence of the revolution. The trip north to a small town on the U.S. side of the border is filled with fear and anxiety for the family as they worry about loved ones left behind and the uncertain future ahead.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: It’s the summer of 1911 in northern Mexico, and thirteen-year-old Evangelina and her family have learned that the rumors of soldiers in the region are true. Her father decides they must leave their home to avoid the violence of the revolution. The trip north to a small town on the U.S. side of the border is filled with fear and anxiety for the family as they worry about loved ones left behind and the uncertain future ahead.

Life in Texas is confusing, though the signs in shop windows that say “No Mexicans” and some people’s reactions to them are all-too clear. At school, she encounters the same puzzling resentment. The teacher wants to give the Mexican children lessons on basic hygiene! And one girl in particular delights in taunting the foreign-born students. Why can’t people understand that—even though she’s only starting to learn English—she’s just like them?

With the help and encouragement of the town’s doctor and the attentions of a handsome boy, Evangelina begins to imagine a new future for herself. But will the locals who resent her and the other new immigrants allow her to reach for and follow her dreams?

MY TWO CENTS: Diana J. Noble’s Evangelina Takes Flight is timely to a startling degree. As a work of historical fiction, Noble’s portrayal of upheaval in Mexico caused by the Mexican Revolution and Pancho Villa’s raids on farming villages remains relevant to this day. In confronting the racism and xenophobia rampant at the border, where shops display signs declaring “’No Dogs! No Negroes! No Mexicans! No Perros! No Negros! No Mexicanos!’,” Evangelina’s story parallels contemporary struggles for racial equality (92). As racial tensions build both in the text and in real life, Evangelina’s stand to keep her school desegregated feels remarkably current, and in its demonstration of child activism, Evangelina Takes Flight holds up a powerful example.

Though Noble doesn’t spend much time explaining the political situation of Mexico during the early twentieth century, the book doesn’t suffer from this lack of context. Indeed, told from the first-person point of view of Evangelina, the text should not offer details outside of her awareness. The book begins mere days after Porfirio Díaz was ousted as president of Mexico, an event that certainly would not have reached the secluded rancho where Evangelina lives, let alone Evangelina herself. Yet, as we journey along with the tenacious and imaginative Evangelina from her fictional Mexican town of Mariposa to the United States to escape the violence wrought by Villa, Noble invites the reader to watch Evangelina grow and mature. She might not be able to foment resistance in her native Mexico, but she certainly can in the United States, and eventually does when called upon to stand up for her right to an education.

Though Evangelina is still a child, at least by modern conceptions of childhood (she turns fourteen during the course of the book), she is entrusted with great responsibility, much of it in the field of medicine—leading her to dream of one day becoming a nurse or even a doctor. While this dream defies the limitations put upon her by her race and her gender, Evangelina does cling to some, perhaps stereotypical, tenets of Mexican femininity. She’s excited for her upcoming quinceañera, and she longs for the attention of boys—one boy, in particular: Selim. Evangelina’s blossoming relationship with Selim is doubly interesting because he is Lebanese—a fact that would likely cause some waves among her traditional Mexican family. Though Noble keeps their relationship chaste, the potential of an interracial relationship adds intrigue, and I wish there was more to it. Understandably, however, Evangelina and Selim’s feelings for each other are overshadowed by an upcoming town hall meeting, which will decide if foreign-born students will be allowed to attend school with their white peers.

Though Evangelina Takes Flight confronts historical (and contemporary) racism with aplomb, it still contains some troubling tropes about marginalized peoples, namely the White Savior figure. Evangelina has multiple encounters with the local doctor, Russell Taylor, whose compassion transcends race. Unlike his neighbors, Dr. Taylor is more than willing to help the Mexicans and goes out of his way to treat Evangelina’s Aunt Cristina when she gives birth to twin sons, one of whom is stillborn. Because of his position as the town doctor, Dr. Taylor holds sway with those who seek to segregate the school. He attempts to act as a mediator between the Mexican families and white townspeople, who are led by the mean-spirited Frank Silver. But Dr. Taylor’s intercession strays into White Savior territory when he is the one who discovers a secret that discredits Silver. After revealing Silver’s secret, Dr. Taylor parades Evangelina in front of the crowd at the town hall meeting, ostensibly to demonstrate her intelligence and humanity; but in a moment such as this, she actually becomes less of a humanized figure and more of a token. Additionally, it is not her own words that sway the townspeople to keep the school unified, but her ability to quote from the Bible, in English, that persuades them. While it is possible to read Evangelina as a key activist figure in spite of Dr. Taylor’s intervention, his role in this scene is a little disappointing, coming as it does in a text that otherwise offers so much in regards to racial equality.

Regardless, this book resonated with me on multiple levels. Evangelina’s struggle for independence, respect, and acquiring her own voice is something that many young Latinas, myself included, face today. Noble’s poetic yet accessible prose allows the reader to slip into Evangelina’s world and understand that problems can be overcome with perseverance and bravery. Though the book is at times slow moving and the plot is occasionally sparse, I would argue that such components allow the industrious reader to dive deep and think critically about Evangelina’s circumstances. However, these characteristics may also make this book difficult for reluctant readers. As a result, though this book is marketed as a middle grade novel, it may be more appropriate for experienced or older readers. Even if some parts were troublesome, I still found Evangelina an intriguing and captivating read,. Ultimately, for those looking for a book that faces contemporary issues through the lens of historical fiction, Evangelina Takes Flight certainly fits the bill.

TEACHING TIPS: Evangelina Takes Flight would pair well with other books about school de/segregation or child activists, such as Duncan Tonatiuh’s Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Méndez & Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation or Innosanto Nagara’s A is for Activist. In addition, because of its historical setting, Evangelina would also be useful in teaching about the Mexican Revolution, the history of Texas, or historical race relations in the United States.

Evangelina Takes Flight offers lessons on metaphor and imagery, especially in its use of the butterfly as a symbol of resilience. When Evangelina’s grandfather tells her the story of the migratory butterflies for which her hometown of Mariposa is named, she starts to see the butterfly as an image of strength. Students could be guided to find passages where butterflies are mentioned to see how Noble constructs this extended metaphor. Students may also be encouraged to deconstruct the representations of butterflies on the cover of the book in a discussion about visual rhetoric.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Diana J. Noble was born in Laredo, Texas, and grew up immersed in both Mexican and American cultures. Her young adult novel, Evangelina Takes Flight, is based loosely on her paternal grandmother’s life, but has stories of other relatives and memories from her own childhood woven into every page. It’s received high praise from Kirkus Reviews, Forward Reviews (5 stars), Booklist Online and was recently named a Junior Library Guild selection. [Condensed bio is from the author’s website.]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Diana J. Noble was born in Laredo, Texas, and grew up immersed in both Mexican and American cultures. Her young adult novel, Evangelina Takes Flight, is based loosely on her paternal grandmother’s life, but has stories of other relatives and memories from her own childhood woven into every page. It’s received high praise from Kirkus Reviews, Forward Reviews (5 stars), Booklist Online and was recently named a Junior Library Guild selection. [Condensed bio is from the author’s website.]

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Cris Rhodes is a doctoral student at Texas A&M University – Commerce. She received a M.A. in English with an emphasis in borderlands literature and culture from Texas A&M – Corpus Christi, and a B.A. in English with a minor in children’s literature from Longwood University in her home state of Virginia. Cris recently completed a Master’s thesis project on the construction of identity in Chicana young adult literature.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Cris Rhodes is a doctoral student at Texas A&M University – Commerce. She received a M.A. in English with an emphasis in borderlands literature and culture from Texas A&M – Corpus Christi, and a B.A. in English with a minor in children’s literature from Longwood University in her home state of Virginia. Cris recently completed a Master’s thesis project on the construction of identity in Chicana young adult literature.

a creator stay focused on your projects, all the while managing the challenges of depression?

a creator stay focused on your projects, all the while managing the challenges of depression? FXS: Finding Cheryl Klein was either a blessing or very fortunate depending on your world view. Writing is both solitary and communal and on the communal side my writing got exactly what it needed when it got Cheryl. Her editorial genius complemented all my writing lacks while allowing me to remain true to my writing voice and my writing vision (and reminding me of that voice and vision when I strayed). Yes, there were many times when the editing process was very hard and even at times discouraging but I never lost faith that Cheryl wanted what was best for the book and for the future reader and that kept me going. What I would like to convey to young writers is that they do all they can to enjoy the actual process of writing, of being alone with the work, and have patience with regards to the results they hope to attain. Those results may or may not come, but the process of creating a work that is beautiful and true is still worth the effort. Most of all, find a way to tell your story that is unique to you. Finding that uniqueness takes a lot of honesty and it takes a lot of practice and all the mistakes and rejections that you get will only make you a better writer and a better person if you see writing not as the publication of a book or the recognition that comes with it but as a way of life you are called to live.

FXS: Finding Cheryl Klein was either a blessing or very fortunate depending on your world view. Writing is both solitary and communal and on the communal side my writing got exactly what it needed when it got Cheryl. Her editorial genius complemented all my writing lacks while allowing me to remain true to my writing voice and my writing vision (and reminding me of that voice and vision when I strayed). Yes, there were many times when the editing process was very hard and even at times discouraging but I never lost faith that Cheryl wanted what was best for the book and for the future reader and that kept me going. What I would like to convey to young writers is that they do all they can to enjoy the actual process of writing, of being alone with the work, and have patience with regards to the results they hope to attain. Those results may or may not come, but the process of creating a work that is beautiful and true is still worth the effort. Most of all, find a way to tell your story that is unique to you. Finding that uniqueness takes a lot of honesty and it takes a lot of practice and all the mistakes and rejections that you get will only make you a better writer and a better person if you see writing not as the publication of a book or the recognition that comes with it but as a way of life you are called to live. FXS: I’m re-reading Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless me, Ultima. Rudolfo Anaya is in many ways the father of Mexican-American literature and there is so much to learn from him about the presentation of the Mexican-American experience in a novel. One of my favorite books I always recommend to YA writers is The Book Thief by Markus Zusak because, well, there’s an author who found a way to tell an interesting story about a serious situation in a unique way. But I would also encourage YA writers to read all kinds of books, not just YA. Read fiction and non-fiction works that have nothing to do with what you are writing and you will be surprised by how they ultimately do. Read especially those books where the author’s soul touches yours.

FXS: I’m re-reading Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless me, Ultima. Rudolfo Anaya is in many ways the father of Mexican-American literature and there is so much to learn from him about the presentation of the Mexican-American experience in a novel. One of my favorite books I always recommend to YA writers is The Book Thief by Markus Zusak because, well, there’s an author who found a way to tell an interesting story about a serious situation in a unique way. But I would also encourage YA writers to read all kinds of books, not just YA. Read fiction and non-fiction works that have nothing to do with what you are writing and you will be surprised by how they ultimately do. Read especially those books where the author’s soul touches yours. Francisco X. Stork is the author of Marcelo in the Real World, winner of the Schneider Family Book Award for Teens and the Once Upon a World Award; The Last Summer of the Death Warriors, which was named to the YALSA Best Fiction for Teens list and won the Amelia Elizabeth Walden Award; Irises; and The Memory of Light, which received four starred reviews. He lives near Boston with his wife. You can find him online at

Francisco X. Stork is the author of Marcelo in the Real World, winner of the Schneider Family Book Award for Teens and the Once Upon a World Award; The Last Summer of the Death Warriors, which was named to the YALSA Best Fiction for Teens list and won the Amelia Elizabeth Walden Award; Irises; and The Memory of Light, which received four starred reviews. He lives near Boston with his wife. You can find him online at  DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: Ninety seconds can change a life ― not just daily routine, but who you are as a person. Gretchen Asher knows this, because that’s how long a stranger held her body to the ground. When a car sped toward them and Gretchen’s attacker told her to run, she recognized a surprising terror in his eyes. And now she doesn’t even recognize herself.

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: Ninety seconds can change a life ― not just daily routine, but who you are as a person. Gretchen Asher knows this, because that’s how long a stranger held her body to the ground. When a car sped toward them and Gretchen’s attacker told her to run, she recognized a surprising terror in his eyes. And now she doesn’t even recognize herself.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Elena Foulis has a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies from the University of Arkansas. Her research and teaching interests include U.S. Latina/o literature, and Digital Oral History. She is currently working on a digital oral history collection about Latin@s in Ohio, which has been published as an eBook titled, Latin@ Stories Across Ohio. She currently lives in Cleveland, Ohio.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Elena Foulis has a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies from the University of Arkansas. Her research and teaching interests include U.S. Latina/o literature, and Digital Oral History. She is currently working on a digital oral history collection about Latin@s in Ohio, which has been published as an eBook titled, Latin@ Stories Across Ohio. She currently lives in Cleveland, Ohio.

My very best days as an author are these days, when eager students come rushing up to me after our workshop, asking for selfies; when they tell me about their favorite character; when they marvel at how I learned to cuss like a Salvadoran, or how much I know about making pupusas. I want so much for my books to resonate with them — Their stories inspire me to write young adult novels in the first place.

My very best days as an author are these days, when eager students come rushing up to me after our workshop, asking for selfies; when they tell me about their favorite character; when they marvel at how I learned to cuss like a Salvadoran, or how much I know about making pupusas. I want so much for my books to resonate with them — Their stories inspire me to write young adult novels in the first place.

By Emma Otheguy

By Emma Otheguy My debut picture book, Martí’s Song for Freedom, is a biography of Cuban poet and national hero José Martí, but it is more importantly the story of the connections he made between Latin America and the United States, of how he loved Cuba while living in New York. This book honors Martí’s activism and his fight for justice, and it also tells the story of how Martí learned to go outside-over-there: how he found in the sighing pine trees the sound of the Cuban palmas reales he missed so much, how he lessened the distance between Cuba and New York. He came from everywhere and was on the road to every place, he knew how to dip under the sky and over the sea, how to close the gaps between divided worlds. He used poetry and passion to accomplish it. He too, would know about picture books, and his story is for every child who learns to share and hold our diverse cultures together.

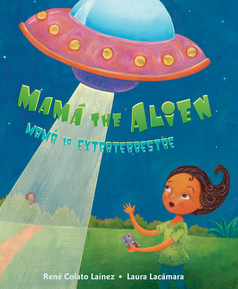

My debut picture book, Martí’s Song for Freedom, is a biography of Cuban poet and national hero José Martí, but it is more importantly the story of the connections he made between Latin America and the United States, of how he loved Cuba while living in New York. This book honors Martí’s activism and his fight for justice, and it also tells the story of how Martí learned to go outside-over-there: how he found in the sighing pine trees the sound of the Cuban palmas reales he missed so much, how he lessened the distance between Cuba and New York. He came from everywhere and was on the road to every place, he knew how to dip under the sky and over the sea, how to close the gaps between divided worlds. He used poetry and passion to accomplish it. He too, would know about picture books, and his story is for every child who learns to share and hold our diverse cultures together. DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Sofía has discovered a BIG secret. Mamá is an alien–una extraterrestre! At least, that’s what it says on the card that fell out of her purse. But Papá doesn’t have an alien card. Does that mean that Sofía is half alien?

DESCRIPTION FROM THE BOOK JACKET: Sofía has discovered a BIG secret. Mamá is an alien–una extraterrestre! At least, that’s what it says on the card that fell out of her purse. But Papá doesn’t have an alien card. Does that mean that Sofía is half alien? ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:  ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR:

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR:  ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Sanjuana C. Rodriguez is an Assistant Professor of Literacy and Reading Education in the Elementary and Early Childhood Department at Kennesaw State University. Her research interests include the early literacy development of culturally and linguistically diverse students, early writing development, literacy development of students who are emergent bilinguals, and Latinx children’s literature. She has published in journals such as Journal of Language and Literacy Education, Language Arts, and Language Arts Journal of Michigan.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Sanjuana C. Rodriguez is an Assistant Professor of Literacy and Reading Education in the Elementary and Early Childhood Department at Kennesaw State University. Her research interests include the early literacy development of culturally and linguistically diverse students, early writing development, literacy development of students who are emergent bilinguals, and Latinx children’s literature. She has published in journals such as Journal of Language and Literacy Education, Language Arts, and Language Arts Journal of Michigan.