by Lila Quintero Weaver

John Parra in his studio in Queens, NY. All photos by Caitlin C. Weaver

Magic flows from the paintbrushes of John Parra, the award-winning illustrator of a growing number of Latino-themed picture books and other illustration work. Here at Latin@s in Kid Lit, we’re ardent fans of John’s art, drenched as it is in color and rich detail, and affirming in its depiction of positive community and family life within Latino settings. Plus, it’s gorgeous—plain and simple—and we can’t resist wondering what’s behind the magic. John invited us into his studio and we had questions.

Lila: Every children’s book you’ve illustrated bears your unmistakable stamp. Developing a personal style doesn’t happen overnight. What’s the story behind yours?

John: My art style really came together in my final year of attending art school. I was fortunate early in my art training to have some amazing teachers and mentors who taught me the traditional fine art techniques of realism, perspective, color theory, and composition. During my mid-college years, I began experimenting more with techniques, such as mixed media, collage, and printmaking. These techniques enabled me to open up and develop a more unique and distinctive visual palette and approach in my work. I also began studying different styles of art genres. I fell in love with folk and outsider art. However, I still felt something was missing as far as an emotional connection to the work I was creating. That changed after a conversation I had with a visiting artist to our school named Salomón Huerta. He was a graduate of our school whose work reflected his Hispanic background and culture. Immediately I felt a connection and a light bulb went off in my head that I, too, could infuse my background, culture, and personality into my work. The first project I did was a series of paintings based on El Dia de los Muertos. I was so excited about the project that I just never stopped. As years have gone by, my work has gradually been updated but still holds on to those inspirational roots from that earlier period.

Lila: It must take scads of research to achieve the “rings true” effect of your illustrations. For example, in P is for Piñata, the illustrations cover a wide range of subject matter, from Aztec deities to cacao pods to folkloric dance. What is your research process like?

John: The first step I do when beginning a project is researching for visual photo references, first through the web, then in books in my library. I tend to look for images not just about the main subject but also in its regional geography, architecture, plants, animals, and anything else that could be related and connected to the issue. I then may delve in and read historical and background info through articles and books. Sometimes there is a good documentary on the topic to gain some insight as well. If possible, speaking to someone with firsthand knowledge of the subject can also bring a wealth of ideas. To me it is very important to be true to the source material when working on a project. I feel blessed to be creating this art, but it is a responsibility to accurately portray the content, otherwise you might fall into stereotypes or misleading subject matters.

John: The first step I do when beginning a project is researching for visual photo references, first through the web, then in books in my library. I tend to look for images not just about the main subject but also in its regional geography, architecture, plants, animals, and anything else that could be related and connected to the issue. I then may delve in and read historical and background info through articles and books. Sometimes there is a good documentary on the topic to gain some insight as well. If possible, speaking to someone with firsthand knowledge of the subject can also bring a wealth of ideas. To me it is very important to be true to the source material when working on a project. I feel blessed to be creating this art, but it is a responsibility to accurately portray the content, otherwise you might fall into stereotypes or misleading subject matters.

Lila: The characters in your scenes include a wide range of skin tones, an important acknowledgment of ethnic diversity within Latino populations–kudos to you for that!

John:. Growing up, I always had a diverse group of family and friends. To me, it seems pretty normal to extend that into my work. I also just enjoy seeing diversity. I think it’s important that all people are represented and as we say, invited to the party.

Lila: One fascinating component to your book illustration is the practice of hiding “Easter eggs.” Please elaborate!

John: I often add funny or inside references in my work for my family and friends to find. One example of this is that I always include a self-portrait character, representing myself as a child, in all my books. I will not give away which character it is, it will be up to the viewer now to find and guess.

Lila: The world of publishing needs more highly skilled Latin@ creators. Based on your experience, what advice would you give to a young person considering illustration as a career?

John: You could probably devote a series of articles to just this one question. Starting out as a new artist can be challenging, with many artistic directions and choices to make. Based on my experience working in the field of freelance illustration, I recommend developing the following four areas.

1. Focus on your artwork and make it as exceptional as possible. It should be a reflection of what you like and have interest in. Create your own voice and style that connects the work to you.

2. Use print promotion and social media to display your work. It is very important to get your art out there in the public. Your artwork should be easily accessible to view online. Blogs, Facebook, and illustration annual competitions can be very helpful for ideas, as well as for showcasing your work. Be consistent, announce successes, and bring awareness to your projects.

3. Include a group of artist friends and colleagues to meet with regularly. This way, you can discuss ideas and potential projects to work on, perhaps even collaborative ones.

4. The business side: Learn as much as possible about contracts and billing. Whether or not you have someone to represent you, it is always important to read as best you can about what you are getting into.

Lila: If you could sit down for a long session of shoptalk with one or more illustrators, living or dead, who would they be, and what would you ask?

Lila: If you could sit down for a long session of shoptalk with one or more illustrators, living or dead, who would they be, and what would you ask?

John: I am a fan of other illustrators as well as anyone else who loves the genre. One of the perks of my job is that I have been able to meet so many other artists whose work I have admired for many years. There are, however, two artists who have passed on whom I would have loved to have sat down and talked shop with. They are Virginia Lee Burton and Maurice Sendak. Both had such an impact on me at an early age, since their books were part of the first illustrations introduced to me. I would love to ask their ideas and intentions when they were working on their most famous stories, plus to see their studio space and how they worked would be wonderfully inspirational.

Lila: As you know, the diversity movement in children’s publishing picked up significant steam in 2014. What were opportunities like for Latin@ illustrators when you started your career? Have you seen changes?

John: I believe the We Need Diverse Books initiative and Walter Dean Myers’ essay in the The New York Times came at a turning point in bringing awareness to examining and appreciating the beauty and diversity in multicultural books. When I began as an illustrator eighteen years ago, there did not seem to be as many projects geared to a diverse population. Over the last few years I have seen progress and greater opportunities for artists with varied voices and backgrounds to shine. I look forward to seeing even more done as we continue to expand and celebrate these wonderful talents.

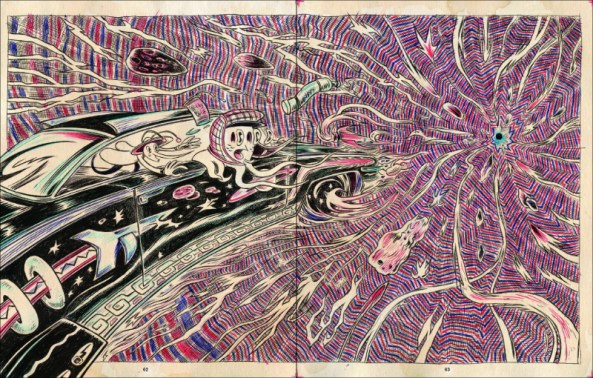

Printer markings indicate page borders. John often uses a limited palette of hues, individually selected for each book.

Lila: Not long ago, I came upon a museum exhibit of Mexican retablos and ex-votos. Is it my imagination, or does your art contain echoes of this beautiful sub-genre of naive art?

Yes! I am a big fan of retablos and ex-votos art. These paintings have that wonderful folk-art tradition of weaving in harrowing stories and miraculous tales. Many of them actually weave text right into the works themselves. A favorite of mine is Mexican retablo artist Alfredo Vilchis. You can find many of his pieces in a great little book entitled: Infinitas Gracias: Contemporary Mexican Votive Painting.

Lila: We’re looking forward to the next John Parra book! What’s in the pipeline?

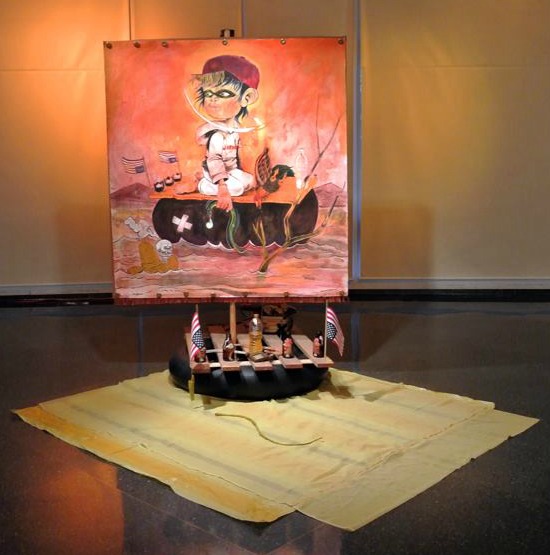

Sketches from John’s newest project., Marvelous Cornelius.

John: I do have a new children’s book that I finished recently coming out this summer (2015) with Chronicle Books. It is titled: Marvelous Cornelius: Hurricane Katrina and the Spirit of New Orleans, written by Phil Bildner. The story is about a real-life gentleman named Cornelius Washington, a sanitation worker in New Orleans. He was considered a local folk hero and known in the neighborhood and the French Quarter by his positive and charismatic personality. As the book develops, the story goes into the events of Hurricane Katrina. We then see the effects on Cornelius and his neighborhood, as he reacts and resolves what to do after the storm.

[Note: Catch more views from Marvelous Cornelius on the Latin@s in Kid Lit Pinterest boards!]

[Note: Catch more views from Marvelous Cornelius on the Latin@s in Kid Lit Pinterest boards!]

John: Another exciting event will be an artist presentation scheduled this coming year in June. It will be an artist lecture, workshop, and book signing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art here in New York City. I am really looking forward to it. It is a dream to be a part of such an amazing and historic institution.

As for new work, I am also starting a big new illustration project with details that I hope to share soon.

John Parra is an acclaimed illustrator, fine artist, designer and educator. His children’s book illustrations have received many awards, among them, The Golden Kite Award from The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators; The Pura Belpré Honor Award; The Américas Book Award; Commended Title from CLASP, The International Latino Book Award; The Christopher Award. John grew up in Santa Barbara, California, where his artistic life began. He now resides in Queens, NY, with his wife, Maria. Keep up with John’s work through his website.

John Parra is an acclaimed illustrator, fine artist, designer and educator. His children’s book illustrations have received many awards, among them, The Golden Kite Award from The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators; The Pura Belpré Honor Award; The Américas Book Award; Commended Title from CLASP, The International Latino Book Award; The Christopher Award. John grew up in Santa Barbara, California, where his artistic life began. He now resides in Queens, NY, with his wife, Maria. Keep up with John’s work through his website.

Views of the studio reveal original pieces, as well as John’s guitars from a band he played with in California. Although he holds on to a few illustrations that he feels especially attached to, many are sold in galleries or through his website. A recent exhibit of originals in Brazil sold out!

Born and raised in the Bay Area, Robert Trujillo is a visual artist and father who employs illustration, storytelling, and public art to tell tales. These tales manifest in a variety of forms and they reflect the artist’s cultural background, dreams, and political / personal beliefs. He can be found online and on Twitter at @RobertTres.

Born and raised in the Bay Area, Robert Trujillo is a visual artist and father who employs illustration, storytelling, and public art to tell tales. These tales manifest in a variety of forms and they reflect the artist’s cultural background, dreams, and political / personal beliefs. He can be found online and on Twitter at @RobertTres.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Juanita lives in New York and is Mexican. Felipe lives in Chicago and is Panamanian, Venezuelan, and black. Michiko lives in Los Angeles and is Peruvian and Japanese. Each of them is also Latino.

DESCRIPTION FROM THE PUBLISHER: Juanita lives in New York and is Mexican. Felipe lives in Chicago and is Panamanian, Venezuelan, and black. Michiko lives in Los Angeles and is Peruvian and Japanese. Each of them is also Latino.

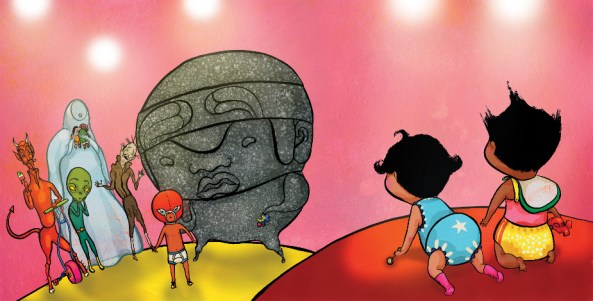

What are these ingredients? La Llorna. El Chamuco. El Extraterrestre. La Cabeza Olmeca. Las Momias. These are the protagonists that star in countless cuentos told and re-told in Mexican and Chicano families. Yuyi presents a dynamic cuento of a boy-hero in a wrestling mask, un niño luchador, who through wit, humor, ganas, and family teamwork, outsmarts these terrifying figures of Mexican and Chicano cultural mythology. As Yuyi reminded us in her acceptance speech, children’s imaginative capacity is an empowering tool that enables them to confront life situations with positive resilience. In addition to her prepared remarks, Yuyi described her own imaginative process as a child, where she was able to transform the often scary and mysterious cultural myths of La Llorona and El Chamuco into figures she could contend with and, perhaps most importantly, learn to play with.

What are these ingredients? La Llorna. El Chamuco. El Extraterrestre. La Cabeza Olmeca. Las Momias. These are the protagonists that star in countless cuentos told and re-told in Mexican and Chicano families. Yuyi presents a dynamic cuento of a boy-hero in a wrestling mask, un niño luchador, who through wit, humor, ganas, and family teamwork, outsmarts these terrifying figures of Mexican and Chicano cultural mythology. As Yuyi reminded us in her acceptance speech, children’s imaginative capacity is an empowering tool that enables them to confront life situations with positive resilience. In addition to her prepared remarks, Yuyi described her own imaginative process as a child, where she was able to transform the often scary and mysterious cultural myths of La Llorona and El Chamuco into figures she could contend with and, perhaps most importantly, learn to play with.