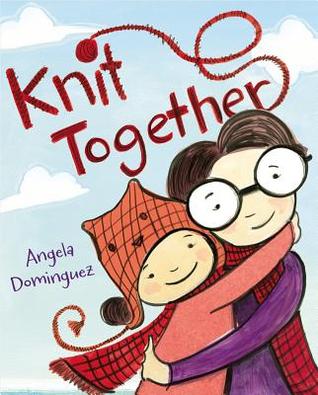

GROWING UP PEDRO. Text and Illustrations copyright 2015 Matt Tavares. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Inc., Somerville, MA.

By Lila Quintero Weaver

When author-illustrator Matt Tavares turns his focus on a children’s book topic, beautiful things happen. We love what he did with Growing Up Pedro: How the Martinez Brothers Made It from the Dominican Republic All the Way to the Major Leagues, a stirring picture book biography of the Dominican baseball great Pedro Martinez and his highly influential brother Ramón. Now we’re turning our focus on Matt himself, a prolific producer of books for kids, who agreed to answer a few of our burning questions.

Latin@s in Kid Lit: Wow, your paintings are magnificent! They’re highly realistic yet deliver much more than faithful representation, in terms of their emotive power and aesthetics. Please tell us about your journey to professional illustration.

Matt: Wow, thank you! That’s certainly what I always try to do, so it’s very nice to hear my pictures described that way. Even if I’m painting a realistic scene, there is always something I can do to heighten it, to go beyond what a photograph might show.

Matt’s been drawing baseball figures since childhood.

I’ve always loved to draw. Even when I was 4 or 5 years old, I thought of myself as an artist. I drew all the time, and knew I wanted to be some kind of artist when I grew up. It wasn’t until I was a junior at Bates College that I decided I wanted to illustrate picture books. I wrote and illustrated a picture book as my senior thesis. I spent my whole senior year working on it. After that, things happened pretty quickly- I found an agent who liked it, and she shopped it around to publishers, and found Candlewick Press. They basically asked me to do the whole thing over again with the guidance of an editor and art director, which I happily did. Then in 2000, Zachary’s Ball was published, my first book.

Matt hard at work in his studio

LiKL: You’re not only an illustrator—you also write. Can you walk us through the process of creating a picture book, starting from the idea phase and ending with publication?

Matt: Sure. The beginning part is pretty messy, where I just have all kinds of ideas floating around and I write everything down in my notebook. From there, most of the ideas just wither away, but every now and then one of them grows into something I think I might actually be able to work with.

I always write the words first, then once I figure out how to divide it up into pages, I do rough sketches. And there is always a lot of back and forth between the words and pictures. In a picture book, part of the story will be told with words and part of the story will be told with pictures. Once I start figuring out what the pictures are going to be, I realize I don’t need some of the words.

Once all my sketches are approved by my art director (after a couple rounds of revisions, usually), I start working on the final illustrations. That part usually takes 4 to 6 months. The whole process, from start to finish, can take 9 months to a year, depending on the book. Then once all the illustrations are done, it’s about a year until it comes out in stores.

LiKL: By my count, seven of your published children’s books center on baseball stories, including Growing Up Pedro, your picture-book bio of Dominican major league star Pedro Martinez, which we reviewed in November. What’s your connection to the sport?

Matt: Baseball is just something I’ve always loved. I grew up near Boston and have great memories of going to Fenway Park to watch the Red Sox play. When I was a kid, I was really into collecting baseball cards, watching baseball, playing baseball and wiffle ball. It’s one of the few things that has been a constant in my life from the very beginning. So when I started writing books for kids, baseball was a natural subject. Honestly, I wasn’t a big reader when I was a kid, but I would read anything if it was about baseball. I know there are still kids like that, and I hope they find my books!

LiKL: Speaking of Growing Up Pedro, you must have done a great deal of research on Pedro Martinez’s life and career, not to mention baseball in general and Dominican life. Fill us in.

Matt: This was my fourth baseball biography, but it was the first about a player I actually got to watch play. So this book was very personal for me. I read a lot of interviews and articles, but I also relied on my own memories of being at Fenway when Pedro was pitching. When he was on the mound, Fenway Park transformed into a different place. There was this electricity that surrounded him. I was excited to try to capture that in a book.

In the Dominican Republic, local children were happy to pose for photos Matt would use in illustrating Growing Up Pedro.

I also traveled to the Dominican Republic when I was working on Growing Up Pedro, which was amazing. Instead of just finding pictures online, I actually got to go to places that still look how they did when Pedro was a kid. I took tons of pictures. It was incredible to be able to go home after that trip and use all these experiences that were fresh in my mind and put them right into my book. It really helped me feel personally connected to the whole story.

LiKL: On this blog, we highlight excellent kid lit that focuses on Latino/a characters, something you pulled off beautifully in Growing Up Pedro. As far as you can tell, has this picture book expanded your reach into the Latino community?

Meeting young fans at book events

Matt: Absolutely, and that’s been really great. I was thrilled when I found out Candlewick was going to do a Spanish edition of the book, because I know that Pedro is a hero to millions of Spanish-speaking people. I love knowing that kids can read Pedro’s story in English or Spanish.

It’s such a powerful thing when a kid can see a bit of themselves in a character, and I think a lot of people have made that connection with Pedro. For some kids it’s because he grew up poor, or even just that he was skinny and small. But I think the fact Pedro is Latino definitely helps a lot of Latino/a readers feel more connected to the story.

GROWING UP PEDRO. Text and Illustrations copyright 2015 Matt Tavares. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Inc., Somerville, MA.

LiKL: Suppose you could hang around the studios of any three illustrators—living or dead—for the purpose of asking questions and observing technique. Who would those illustrators be and why?

Matt: Tough to pick three… I’ll say Chris Van Allsburg, because he’s one of my all-time favorite illustrators, and I would love to watch him work. I would probably just take pictures of all his art supplies then go to the art store and buy all the same stuff. Maurice Sendak, because he was a genius and was always so fascinating in interviews. I never got to meet him. And Jerry Pinkney. I did a book signing with him once, and he was so nice and humble and approachable. He’s been making books for so long, and has had so much success. I’d love to spend some time with him and maybe pick up some good habits.

LiKL: Naturally, we’re curious to know what’s next from Matt Tavares. If you’re free to share, tell us about books already in production, or a project still shiny with wet paint.

Matt: My next book is Crossing Niagara, which is a picture book about The Great Blondin, the first person to walk across Niagara Falls on a tightrope. That comes out in April. Then I have another picture book biography that I illustrated with Candlewick that comes out in Spring 2017, about the first woman pilot. And right now I’m just starting final art for a book I wrote that comes out in Fall 2017. This one is going to be a very new direction for me- it’s fiction, and the main characters are birds. I’m very excited to try something new.

Writer, illustrator, baseball lover! Learn more about Matt Tavares and his books at his official website.

Writer, illustrator, baseball lover! Learn more about Matt Tavares and his books at his official website.

Angela Dominguez

Angela Dominguez