.

.

Interview by Romy Natalia Goldberg

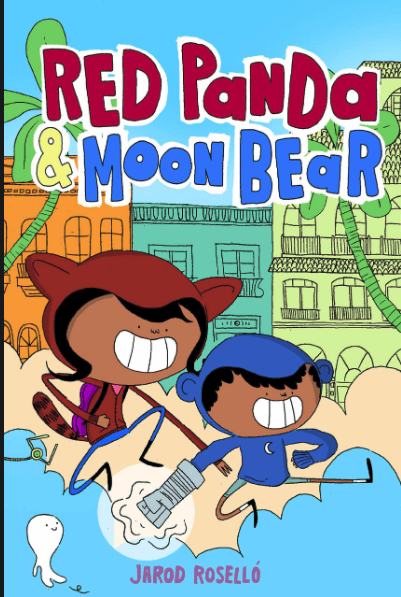

Please enjoy this interview with Jarod Roselló, the author and illustrator of the Red Panda & Moon Bear graphic novel series, and translator Eva Ibarzabal, who helped create the Spanish version, Panda Roja y Oso Lunar.

Romy Natalia Goldberg: First of all, congratulations on both versions of Red Panda & Moon Bear! It’s exciting to have another Latinx graphic novel to add to our shelves, especially one with a Spanish translation.

Jarod Roselló: Thank you! I’m so excited to have it in the world. I immediately sent a copy to my abuela!

The original English version, Red Panda & Moon Bear, was published in July 2019 and Panda Roja y Oso Lunar was published in July of 2020. What was the genesis of the Spanish translation? Was it in the works from the beginning or did the opportunity present itself further along in the process?

Jarod: It wasn’t an original plan, or at least not one that was shared with me at the time I was working on the book. Shortly after Red Panda & Moon Bear was released, IDW Publishing (Top Shelf’s parent company) announced a new Spanish-language initiative, and then I got an email from my editor that my book had been selected by IDW to be translated as part of the first wave of Spanish-language books.

Beforehand I said “original English version” but that begs the question – when you created these characters and wrote the original manuscript was it all in English in your head? Or were there some scenes or phrases that naturally popped into your head in Spanish first?

Jarod: English is my primary language, despite the fact I was raised in Miami by my Cuban family, and spoke Spanish with certain family members who didn’t speak English. We didn’t speak Spanish much in my house, with my siblings and parents, but still, there are certain words, expressions, and phrases that only exist in Spanish for us. I think it’s easy to explain that growing up bilingual or in a bilingual setting, means that you “switch” between languages. But when I use Spanish terms—in my books, or in real life with my own kids—it doesn’t necessarily feel like two separate languages. I wanted the English edition to feel that way as well, that when Spanish appeared it wasn’t a breach in the English, it’s just the way language developed and is used in these communities and families. That matched my own experience growing up and felt true for me.

I’m curious about the process for creating a translation. In addition to yourself, who else was involved?

Jarod: It started with my editor letting me know they were looking for a translator. We decided early on, that someone else would translate it, and that we would look for someone who was either Cuban, Cuban American, or spoke a more Caribbean Spanish, so the setting would hold.

Eva Ibarzabal: When they contacted me for the first time I had serious doubts. I had already translated fiction and biographies for young readers, but graphic novels were way beyond my comfort zone. The approach is completely different, you have space constraints and a unique style, but then I read the English version and fell in love with the characters and the story. I’m very happy with the outcome.

There are so many variations of Spanish out there. In Spanish translations, this is something that really comes through in figures of speech and exclamations. I learned some new ones reading Panda Roja y Oso Lunar, which I assume are specific to the Caribbean. Did everyone speak the same “type” of Spanish? If not were there particular scenes and word choices that generated debate?

Eva: Jarod and I have something in common, we are both Cuban-Americans. I lived in Miami for a short period of time before moving to Puerto Rico, and my family was very attached to their roots and ancestry. I guess that helped me capture the essence of the characters and their way of speaking. I just had to dust off some memories of my own childhood and the comics I used to read back then. Other than that, some sounds and the use of onomatopoeia are the most difficult to translate because in Spanish we tend to use lengthy descriptions instead.

Jarod: There were also some interesting conversations after we got Eva’s script, because we also had a Spanish-language editor working on it, and they had notes about some of the expressions and suggestions for changes. But sometimes, I’d never heard of the expression the editor wanted to use. In the end, my editor let me cast the tie-breaking vote on which one we would use.

This book feels different from other translations I’ve read. It’s clear you had a specific goal in mind.

Jarod: This stemmed from an early conversation with my editor that it shouldn’t just be a translated book, but that the Spanish edition should be a Spanish-language universe, and it should be read that way.

Eva: I think the best compliment a translator can receive is that their work does not read as a translation. You have to digest all the ideas and convey the meaning in the most natural way possible; the text should flow. In the case of a graphic novel, an additional challenge is to be concise, because Spanish tends to be more wordy. I was counting words and measuring spaces all the time to be sure the new text would fit and not take space from the illustrations. It’s definitely like a parallel universe, as Jarod says.

Jarod: And you did such a fabulous job with that, Eva. I loved how you were able to preserve the puns and references, and still capture the spirit and energy of the book.

It sounds like there were two different processes you had to go through – translating the copy and adjusting the content. Let’s talk about the copy first. For a panel where you had a basic sentence that needed to go from Spanish to English, what did you do? I assume it wasn’t as easy as just copying text from a Spanish script and plunking it into your text bubbles.

Jarod: As Eva mentioned, Spanish tends to be longer, not just in the construction of sentences, but individual words can be very long, which created some visual challenges fitting them into the existing word balloons.

One benefit to being both the letterer and the original artist was that I could adjust the word balloons to accommodate the Spanish, just how I write out the English first, then draw the word balloon around it. It’s not quite that simple, either, though, because the word balloons take up visual space in the panel. So, often, I had to redraw certain panels so that relevant imagery wasn’t being blocked or so the visual composition still looked the way I would want it to look.

I wanted to put the same care and attention to detail in the Spanish edition. And I also really love that the English and Spanish editions are not exactly the same: some drawings are new, some panels are modified, and even corrected a few tiny mistakes I found along the way!

Now let’s talk about what sounds like a much more complex process – altering content, both the text and actual images, that simply would not make sense if translated directly into Spanish.

Jarod: A good example of this was in chapter 7. The kids and the dogs head to the library. The kids are reading a picture book in Spanish and the dogs are curious because they don’t know Spanish. There’s a brief conversation about how the kids’ Spanish is a little rusty, and that they need to practice more. In the Spanish edition, though, it’s a Spanish-speaking world, so this conversation wouldn’t have made any sense, because the dogs are speaking Spanish.

So, I rewrote the opening pages to that chapter so that the characters are talking about how comics are real books, and reading comics counts as reading. I redrew a few of the panels as well and edited the others. And we sent that scene separately to Eva to be translated, and then we went back in and swapped pages to put it all together.

Eva: And I was glad of that decision because I already had a big question mark on that page! That’s the advantage of all the team working together and communicating all along. I think the solution was perfect.

Red Panda & Moon Bear: The Curse of The Evil Eye is slated for January 2022. Will there be a Spanish translation as well? Did the experience of translating the first book alter the way you’re writing and drawing the second installment at all?

Jarod: I don’t know if they’re planning a Spanish translation of The Curse of the Evil Eye, but I really hope so! The experience of relettering and sitting with my book in Spanish definitely affected how I approached book 2. The Spanish and Cuban roots of the setting are more visible, there’s a lot more Spanish, too. I feel like reading Eva’s translation taught me what this world looks like in Spanish, and even gave me a little confidence to use more of it. I feel like I can hear the character’s voices more clearly, and that’s helped me understand them and their world better.

Eva: From my point of view, it was a great learning experience which I really enjoyed. So I hope to be part of the team again if the decision to have a Spanish version is made. How about a simultaneous launching? That would be awesome!

.

Jarod Roselló is a Cuban American writer, cartoonist, and teacher. He is the author of the middle-grade graphic novel Red Panda & Moon Bear, a Chicago Public Library and New York Public Library 2019 best book for young readers, and a 2019 Nerdy Award winner for graphic novels. Jarod holds an MFA in Creative Writing and a PhD in Curriculum & Instruction, both from The Pennsylvania State University. Originally from Miami, he now lives in Tampa, Florida, with his wife, kids, and dogs, and teaches in the creative writing program at the University of South Florida. You can reach him at http://www.jarodrosello.com and @jarodrosello (Twitter & Instagram)

.

.

Eva Ibarzabal is a Cuban-Puerto Rican translator, writer and media and language consultant. After completing a BA in Modern Languages and a MA in Translation, Eva worked in print media and television for 20 years, winning multiple accolades for the production of Special News Programs. A few years ago, her love for Literature made her switch to Literary Translation. Her works include biographies, fiction and children books. Her English to Spanish Translation of El mundo adorado de Sonia Sotomayor won the International Latino Book Award in 2020.

.

.

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER: Romy Natalia Goldberg is a Paraguayan-American travel and kid lit author with a love for stories about culture and communication. Her guidebook to Paraguay, Other Places Travel Guide to Paraguay, was published in 2012 and 2017 and led to work with “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown,” and The Guardian. She is an active SCBWI member and co-runs Kidlit Latinx, a Facebook support group for Latinx children’s book authors and illustrators.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Cathy Camper is the author of Lowriders in Space, Lowriders to the Center of the Earth and Lowriders Blast from the Past, with a fourth volume in the works, all from Chronicle Books. She has a forthcoming picture book, Ten Ways to Hear Snow (Dial/Penguin), and also wrote Bugs Before Time: Prehistoric Insects and Their Relatives (Simon & Schuster). Her zines include Sugar Needle and The Lou Reeder, and she’s a founding member of the Portland Women of Color zine collective. A graduate of VONA/Voices writing workshops for people of color in Berkeley, California, Cathy works as a librarian in Portland, Oregon, where she does outreach to schools and kids in grades K-12. Cathy is represented by Jennifer Laughran of Andrea Brown Literary Agency. For insights on the creative originas of the Lowriders series, read Cathy’s Camper’s

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Cathy Camper is the author of Lowriders in Space, Lowriders to the Center of the Earth and Lowriders Blast from the Past, with a fourth volume in the works, all from Chronicle Books. She has a forthcoming picture book, Ten Ways to Hear Snow (Dial/Penguin), and also wrote Bugs Before Time: Prehistoric Insects and Their Relatives (Simon & Schuster). Her zines include Sugar Needle and The Lou Reeder, and she’s a founding member of the Portland Women of Color zine collective. A graduate of VONA/Voices writing workshops for people of color in Berkeley, California, Cathy works as a librarian in Portland, Oregon, where she does outreach to schools and kids in grades K-12. Cathy is represented by Jennifer Laughran of Andrea Brown Literary Agency. For insights on the creative originas of the Lowriders series, read Cathy’s Camper’s  ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Raúl the Third is an award-winning illustrator, author, and artist living in Boston. His work centers on the contemporary Mexican-American experience and his memories of growing up in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Lowriders in Space was nominated for a Texas BlueBonnet award in 2016-2017 and Raúl was awarded the prestigious Pura Belpré Award for Illustration by the American Library Association for Lowriders to the Center of the Earth. He was also a contributor to the SpongeBob Comics series. Raúl wrote and illustrated the picture book ¡Vamos! Let’s Go to The Market!, which Versify will publish on April 2. For a fun and lively conversation about art, comics, growing up in El Paso and more, check out this one-of-a-kind

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR: Raúl the Third is an award-winning illustrator, author, and artist living in Boston. His work centers on the contemporary Mexican-American experience and his memories of growing up in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Lowriders in Space was nominated for a Texas BlueBonnet award in 2016-2017 and Raúl was awarded the prestigious Pura Belpré Award for Illustration by the American Library Association for Lowriders to the Center of the Earth. He was also a contributor to the SpongeBob Comics series. Raúl wrote and illustrated the picture book ¡Vamos! Let’s Go to The Market!, which Versify will publish on April 2. For a fun and lively conversation about art, comics, growing up in El Paso and more, check out this one-of-a-kind  ABOUT THE REVIEWER: A Mexican-American author from deep South Texas, David Bowles is an assistant professor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Recipient of awards from the American Library Association, Texas Institute of Letters and Texas Associated Press, he has written a dozen or so books, including Flower, Song, Dance: Aztec and Mayan Poetry, the critically acclaimed Feathered Serpent, Dark Heart of Sky: Mexican Myths, and They Call Me Güero: A Border Kid’s Poems. In 2019, Penguin will publish The Chupacabras of the Rio Grande, co-written with Adam Gidwitz, and Tu Books will release his steampunk graphic novel Clockwork Curandera. His work has also appeared in multiple venues such as Journal of Children’s Literature, Rattle, Strange Horizons, Apex Magazine, Nightmare, Asymptote, Translation Review, Metamorphoses, Huizache, Eye to the Telescope, and Southwestern American Literature. In April 2017, David was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters for his literary work.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: A Mexican-American author from deep South Texas, David Bowles is an assistant professor at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Recipient of awards from the American Library Association, Texas Institute of Letters and Texas Associated Press, he has written a dozen or so books, including Flower, Song, Dance: Aztec and Mayan Poetry, the critically acclaimed Feathered Serpent, Dark Heart of Sky: Mexican Myths, and They Call Me Güero: A Border Kid’s Poems. In 2019, Penguin will publish The Chupacabras of the Rio Grande, co-written with Adam Gidwitz, and Tu Books will release his steampunk graphic novel Clockwork Curandera. His work has also appeared in multiple venues such as Journal of Children’s Literature, Rattle, Strange Horizons, Apex Magazine, Nightmare, Asymptote, Translation Review, Metamorphoses, Huizache, Eye to the Telescope, and Southwestern American Literature. In April 2017, David was inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters for his literary work. DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: How would a kitchen maid fare against a seven-headed dragon? What happens when a woman marries a mouse? And what can a young man learn from a thousand leaf cutter ants? Famed Love and Rockets creator Jaime Hernandez asks these questions and more as he transforms beloved myths into bold, stunning, and utterly contemporary comics. Guided by the classic works of F. Isabel Campoy and Alma Flor Ada, Hernandez’s first book for young readers brings the sights and stories of Latin America to a new generation of graphic novel fans around the world.

DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK: How would a kitchen maid fare against a seven-headed dragon? What happens when a woman marries a mouse? And what can a young man learn from a thousand leaf cutter ants? Famed Love and Rockets creator Jaime Hernandez asks these questions and more as he transforms beloved myths into bold, stunning, and utterly contemporary comics. Guided by the classic works of F. Isabel Campoy and Alma Flor Ada, Hernandez’s first book for young readers brings the sights and stories of Latin America to a new generation of graphic novel fans around the world. ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR: Jaime Hernandez is the co-creator, along with his brothers Gilbert and Mario, of the comic book series Love and Rockets. Since publishing the first issue of Love and Rockets in 1981, Jaime has won an Eisner Award, 12 Harvey Awards, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. The New York Times Book Review calls him “one of the most talented artists our polyglot culture has ever produced.” Jaime decided to create The Dragon Slayer, his first book for young readers, because “I thought it would be a nice change of pace from my usual grown-up comics.” He read through tons of folktales to choose these three. What made them stand out? Maybe he saw himself in their characters. Jaime says, “I’m not as brave as the dragon slayer, but I can be as caring. I’m as lazy as Tup without being as resourceful. I am not as vain as Martina, but I can be as foolish.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR: Jaime Hernandez is the co-creator, along with his brothers Gilbert and Mario, of the comic book series Love and Rockets. Since publishing the first issue of Love and Rockets in 1981, Jaime has won an Eisner Award, 12 Harvey Awards, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. The New York Times Book Review calls him “one of the most talented artists our polyglot culture has ever produced.” Jaime decided to create The Dragon Slayer, his first book for young readers, because “I thought it would be a nice change of pace from my usual grown-up comics.” He read through tons of folktales to choose these three. What made them stand out? Maybe he saw himself in their characters. Jaime says, “I’m not as brave as the dragon slayer, but I can be as caring. I’m as lazy as Tup without being as resourceful. I am not as vain as Martina, but I can be as foolish.”

Isabel Campoy (left, Introduction, “Imagination and Tradition”) and Alma Flor Ada (right, Martina Martinez and Pérez the Mouse) are authors of many award-winning children’s books, including Tales Our Abuelitas Told, a collection of Hispanic folktales that includes Martina Martinez and Pérez the Mouse. Alma Flor says, “My favorite moment in the story is when Ratón Pérez is pulled out of the pot of soup!” As scholars devoted to the study of language and literacy, Alma Flor and Isabel love to share Hispanic and Latino culture with young readers. “Folktales are a valuable heritage we have received from the past, and we must treasure them and pass them along,” Isabel says. “If you do not have roots, you will not have fruits.”

Isabel Campoy (left, Introduction, “Imagination and Tradition”) and Alma Flor Ada (right, Martina Martinez and Pérez the Mouse) are authors of many award-winning children’s books, including Tales Our Abuelitas Told, a collection of Hispanic folktales that includes Martina Martinez and Pérez the Mouse. Alma Flor says, “My favorite moment in the story is when Ratón Pérez is pulled out of the pot of soup!” As scholars devoted to the study of language and literacy, Alma Flor and Isabel love to share Hispanic and Latino culture with young readers. “Folktales are a valuable heritage we have received from the past, and we must treasure them and pass them along,” Isabel says. “If you do not have roots, you will not have fruits.” ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Marcela was born in Brazil and moved to the U.S. at the age of three, growing up in South Florida. She is now the Library Director at Lewiston Public Library in Maine. Marcela holds a Master of Library and Information Science degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she Concentrated on community informatics and library services to teens. She is a copy editor for

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Marcela was born in Brazil and moved to the U.S. at the age of three, growing up in South Florida. She is now the Library Director at Lewiston Public Library in Maine. Marcela holds a Master of Library and Information Science degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she Concentrated on community informatics and library services to teens. She is a copy editor for  Earlier this week, we published a review of

Earlier this week, we published a review of  By Alberto Ledesma

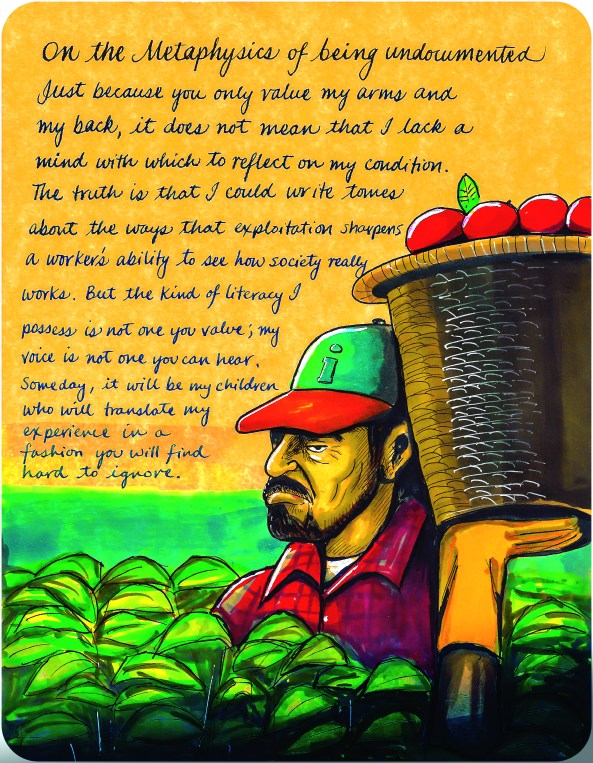

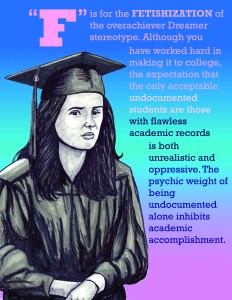

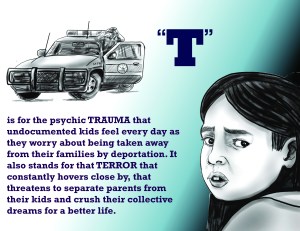

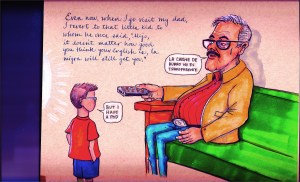

By Alberto Ledesma The creation of the DACA policy inspired me to return to the questions I had about what being undocumented meant in the United States. But, instead of writing more essays about this issue, I decided to draw cartoons instead. It all happened because of that Summer Bridge class I was teaching when the undocumented student movement exploded across the United States. Though I was excited about doing a lecture about the undocumented student movement, my students had expressed a frustration with the amount of work that I had already assigned them. So, in order to pique their interest, I tapped into and old and neglected talent and drew a quick sketch of “A Day in the Life of an Undocumented Student.” Though my students had complained about all the work that they had had to do, I noticed that many of them began doing research on the movement on their own. So, I sketched other cartoons and shared them via Facebook. All of the sudden, I began getting hundreds of friend requests and they began asking me to draw more cartoons, to share my experience though art. After several years of doing so, of drawing vignettes based on my undocumented life, I had the makings of a book.

The creation of the DACA policy inspired me to return to the questions I had about what being undocumented meant in the United States. But, instead of writing more essays about this issue, I decided to draw cartoons instead. It all happened because of that Summer Bridge class I was teaching when the undocumented student movement exploded across the United States. Though I was excited about doing a lecture about the undocumented student movement, my students had expressed a frustration with the amount of work that I had already assigned them. So, in order to pique their interest, I tapped into and old and neglected talent and drew a quick sketch of “A Day in the Life of an Undocumented Student.” Though my students had complained about all the work that they had had to do, I noticed that many of them began doing research on the movement on their own. So, I sketched other cartoons and shared them via Facebook. All of the sudden, I began getting hundreds of friend requests and they began asking me to draw more cartoons, to share my experience though art. After several years of doing so, of drawing vignettes based on my undocumented life, I had the makings of a book.

Today, when I attend important lectures and I am really into what the speaker is saying, I don’t take traditional notes. Rather, I take out my sketchbook, my favorite fountain pen, and I start doodling. I judge the quality of a talk by the complexity of the sketches I produce. Indeed, now that I have done a bit more research on it, I have learned that cartooning is an effective form of communication: it allows for better mental digestion of complex ideas; engages multiple intelligences; and, it allows viewers of an image to understand a story from multiple lenses. It is because of this that cartooning has allowed me to communicate the fears I felt when I was undocumented much more effectively than my writing ever could. This is the reason why I created my illustrated memoir, Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer.

Today, when I attend important lectures and I am really into what the speaker is saying, I don’t take traditional notes. Rather, I take out my sketchbook, my favorite fountain pen, and I start doodling. I judge the quality of a talk by the complexity of the sketches I produce. Indeed, now that I have done a bit more research on it, I have learned that cartooning is an effective form of communication: it allows for better mental digestion of complex ideas; engages multiple intelligences; and, it allows viewers of an image to understand a story from multiple lenses. It is because of this that cartooning has allowed me to communicate the fears I felt when I was undocumented much more effectively than my writing ever could. This is the reason why I created my illustrated memoir, Diary of a Reluctant Dreamer.

Last month, while Alberto Ledesma was at The Ohio State University for a panel on comics and immigration, he stopped for this photo opportunity with Liam Miguel and Ethan Andrés Pérez, sons of our fellow Latinxs in Kid Lit blogger, Ashley Hope Pérez.

Last month, while Alberto Ledesma was at The Ohio State University for a panel on comics and immigration, he stopped for this photo opportunity with Liam Miguel and Ethan Andrés Pérez, sons of our fellow Latinxs in Kid Lit blogger, Ashley Hope Pérez. ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR: Alberto Ledesma, a Mexican-American scholar of literature, holds a doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley. His publications include poetry, academic articles, and short stories, which have appeared in Con/Safos: A Chicana/o Literary Magazine, and in Gary Soto’s Chicano Chapbook Series (#17). He has also published essays in ColorLines and

ABOUT THE AUTHOR-ILLUSTRATOR: Alberto Ledesma, a Mexican-American scholar of literature, holds a doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley. His publications include poetry, academic articles, and short stories, which have appeared in Con/Safos: A Chicana/o Literary Magazine, and in Gary Soto’s Chicano Chapbook Series (#17). He has also published essays in ColorLines and  Joe’s latest book is the YA graphic novel

Joe’s latest book is the YA graphic novel

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at

Cecilia Cackley is a performing artist and children’s bookseller based in Washington, DC, where she creates puppet theater for adults and teaches playwriting and creative drama to children. Her bilingual children’s plays have been produced by GALA Hispanic Theatre and her interests in bilingual education, literacy, and immigrant advocacy all tend to find their way into her theatrical work. You can find more of her work at